When news broke, in July 2023, of David Adjaye’s alleged sexual misconduct, reactions were swift. Forthcoming projects were put on hold or canceled outright, forcing his New York and London offices to downsize. Many clients severed ties with the Ghanaian-British architect. Adjaye’s stellar rise quickly shifted to a meteoric fall.

At the time, the new Princeton University Art Museum (PUAM) envisioned by his firm, Adjaye Associates, with Cooper Robertson, was 50 percent of the way through construction. “It would be a fiction to pretend that someone else designed it—he was the lead architect,” says James Steward, director of the museum since 2009. Nonetheless, Princeton duly distanced itself from Adjaye, who will be absent from the building’s opening, and the university is not the only institution to face such a predicament. In the coming weeks, the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Museum of West African Art in Benin City, Nigeria, will inaugurate buildings designed long ago by the award-winning architect.

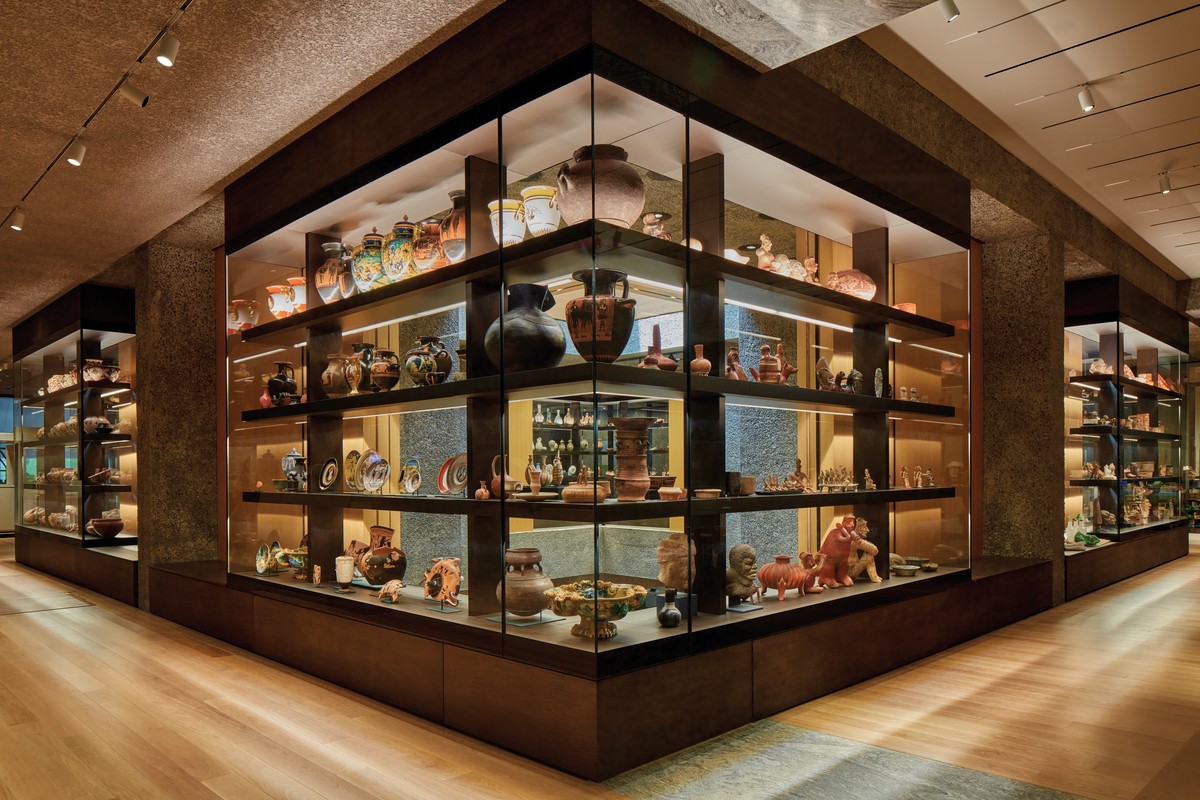

In addition to works from antiquity, the museum boasts an impressive collection of modern and contemporary art. Photo © Richard Barnes, click to enlarge.

“We have to find ways to separate the work from the maker,” says Steward, standing in PUAM’s freshly installed European Art gallery. “How many of these artists would we be able to exhibit if we couldn’t do that?” Indeed, Adjaye is hardly the first person to have both a checkered personal history and an artistic output worthy of study. And the building, as an oeuvre, has much to impart—it is one of the most striking museums to rise in decades.

1

Auguste Rodin’s The Age of Bronze announces the European Art gallery (1), while Guanyin (2) guards the Asian Art gallery. Photos © Richard Barnes

2

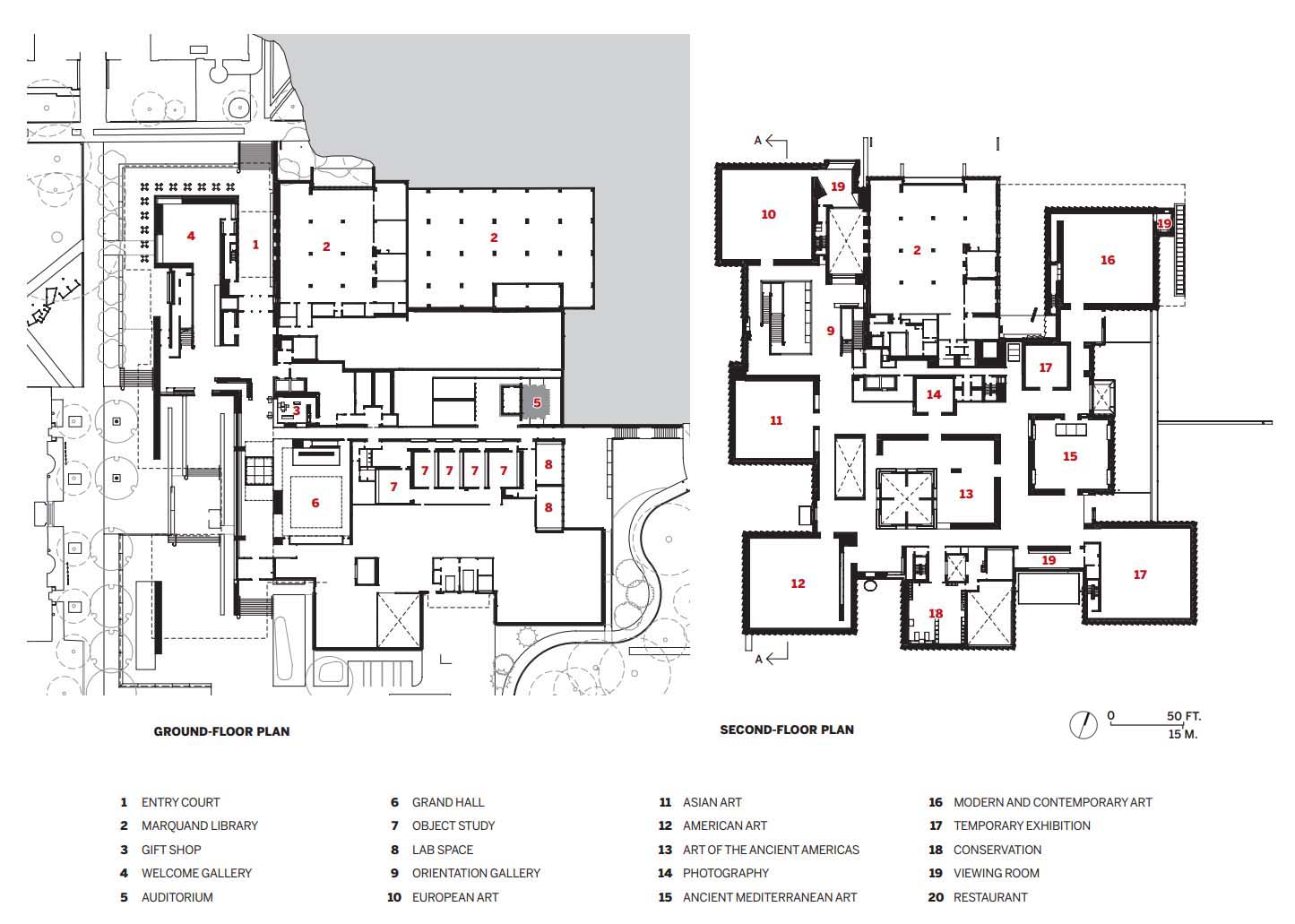

PUAM replaces the former home of the museum, the fine arts library, and the department of arts and archaeology, which, since 1989, had been crammed into a confused, century-spanning amalgam of five buildings, each realized in its own architectural style. When Adjaye Associates and Cooper Robertson were hired in 2018, beating out Michael Maltzan Architecture, Johnston Marklee, and Snøhetta, among others, for the job, the team’s mandate was clear: modernize the facility, increase space for the display of art, and solve what Steward refers to as the “upstairs/downstairs problem”—the perceived value of a work based on its placement within a museum. This meant doubling the building’s size to 146,000 square feet.

Scale, in a historic part of campus dotted by quaint Collegiate Gothic edifices, became the primary challenge. Adjaye proposed breaking up the mammoth mass required to fit the program into nine pavilions—each sized to echo neighboring buildings—which would be stitched together and connected. In its final configuration, seven form galleries, an eighth houses conservation studios, and the ninth (a partially reused and reclad 1960s structure) is the fine arts library. Some are firmly planted on the ground; others daringly cantilever. “The strategy also gave each department its own front door,” Erin Flynn, partner in charge at Cooper Robertson, points out.

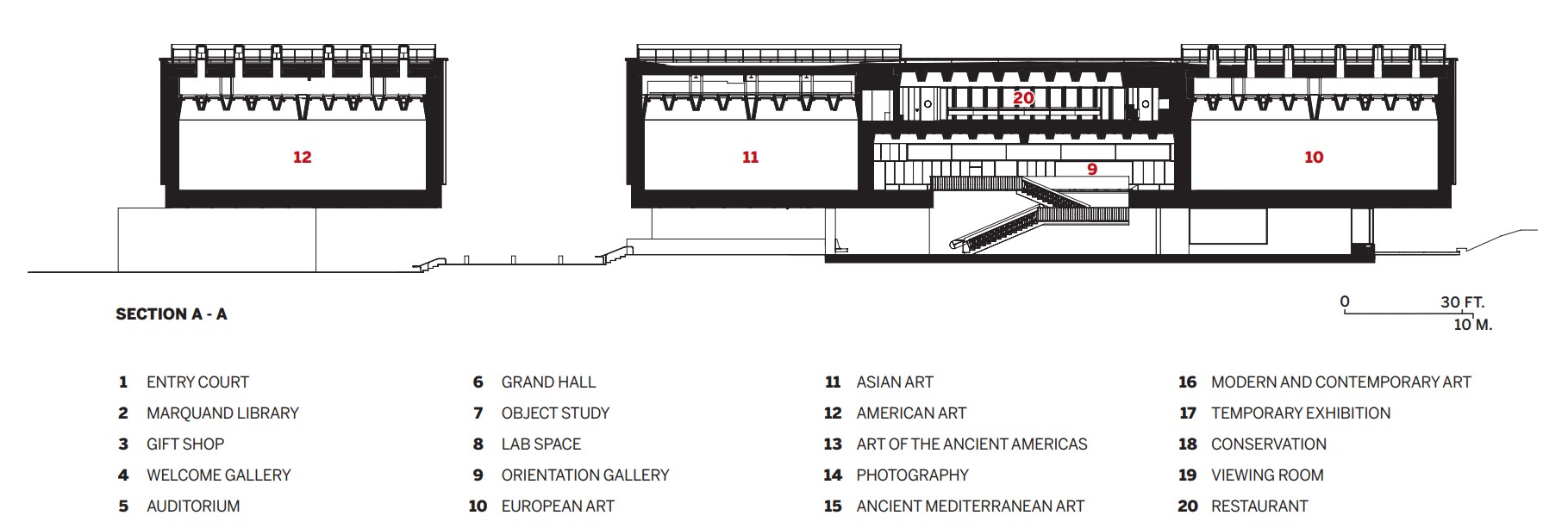

The serrated logic of the precast-concrete facade at times extends to windows. Photo © Richard Barnes

The serrated facade, with its polished tips, rests atop a sandblasted concrete base. Photo © Richard Barnes

A serrated surface of precast concrete jackets PUAM, unifying these constituent pavilions. It is a robust and muscular gesture—neo-Brutalist, even. Adjaye is clearly building on his experience deploying precast concrete—consider the pitted charcoal-colored surface of 130 William Street in Lower Manhattan, or the patterned panels of his Sugar Hill Housing in Harlem (RECORD, October 2014). Each module at PUAM measures 8 feet by 32 feet and includes two serrations, which project beyond the slab cap beneath them. Their tips, filled with a large aggregate, have been ground and polished to expose a field of white and cream-colored calcite. The resultant vertical stripes are radiant, creating a high-contrast complement to the shadows cast by the jagged facade. “We tried different aggregate mixes—a white version, a black version, and an in-between one,” says Ron McCoy, Princeton’s university architect. “When we viewed the mock-ups next to the neighboring classical buildings,” he adds, gesturing to Clio and Whig halls, “we knew which direction to go.”

The precast elements, which rest atop a base of darker heavily sandblasted concrete, are accented by battens of extruded aluminum with an anodized bronze finish. They can be found in small swaths, on canopies, and at the recessed parapet, always arranged to reinforce a vertical grain. It all brings to mind the painstakingly hammered corduroy concrete of Paul Rudolph’s Art & Architecture Building at Yale, and the work of Carlo Scarpa, that obsessive Italian who could so effortlessly weave together tapestries of texture and often trimmed his béton brut with bronze.

Although PUAM can be entered on all sides—another departure from its predecessor—most public visitors will arrive from McCosh Walk, to the north (admission is free of charge). From there, they move down a staircase and beneath one of the floating pavilions before reemerging in an open-air triple-height entry court capped by skylights and a matrix of mass-timber trusses (the first hint of a material that will feature more prominently inside). A monumental installation of a figure, rendered in mosaic tile, metal, and wood (sourced from trees felled on-site) by artist Nick Cave bends down in a prodigious gesture of welcome.

3

4

Visitors walk by a Nick Cave installation in the entry court (4) or beneath a painting by Sean Scully to the south (5). A Mallorcan staircase is set in dialogue with the main one (3). Photos © Richard Barnes (3 & 5), Joseph Hu (4)

5

This entrance lies on a north–south axis that begins with a gate on Nassau Street, the university’s historic town-and-gown boundary, and continues through PUAM. McCoy’s erstwhile predecessor, Ralph Adams Cram, once envisioned a series of courtyards for this same plat (illustrated in a 1910 issue of RECORD as part of Montgomery Schuyler’s American-campus series), and the new structure helps to finally manifest this idea. Inside, the almost dauntingly long corridor has been punctuated by special moments—museumgoers and students pass by a stair hall, which leads to most galleries and the third-floor restaurant, plus a gift shop, architecturally embedded vitrines (in walls and floors), views out to campus, and the remarkable Grand Hall.

A restaurant on the third floor aims to become a destination on campus. Photo © Richard Barnes

This multipurpose room, designed as a lecture hall, venue, and lounge, packs a punch. Rectangular in plan, it is lined with heavily sandblasted concrete. One story up, solid corners have been replaced by glass casework with dense displays of vessels and pottery. Four fins—Steward likens them to flying buttresses—project outward from the center of each wall, drawing eyes upward to a deep cruciform truss nearly 30 feet overhead. The Grand Hall seems to be a long-lost sibling of the vestibule at Louis Kahn’s Yale Center for British Art. Instead of smooth concrete, pewter-colored stainless steel, and oak paneling, Adjaye has leaned into a more textural palette of roughened concrete, oak as well as black spruce, bronze, and terrazzo.

6

7

Sandblasted concrete and oak are combined in the Grand Hall (6). The orientation gallery (7), which stays open to the public, leads to casework that shares walls with the Grand Hall (8). Photos © Richard Barnes

8

The Grand Hall is just as much a technological feat as it is an architectural one. Retractable auditorium-style seating can accommodate up to 236 people. A mechanized stage, flush with the floor, can rise as high as 36 inches. Sliding panels can enclose the casework, and integrated shades can darken the room.

To the east is the 12,000-square-foot education center, the heart of the institution’s pedagogical mission. Five classrooms dedicated to object study (where students and faculty can interrogate pieces), a 70-seat auditorium, seminar rooms, and two wet labs are situated here. “In the old building, we were marshaling about 10,000 objects per academic year,” Steward explains. “We’ve done an analysis of the objects that are most frequently used in teaching, and those are stored on-site.”

A more intimate auditorium, with seats for 70 people, is lined with pink acoustic felt. Photo © Richard Barnes

Back near the entry court, visitors slip off the main north–south axis into a double-height stair hall that leads to the second floor. Here, the use of mass timber as the museum’s load-bearing ceiling structure comes into full view, and the volumetric complexity of the pavilioned scheme becomes clearer.

The museum sits along a campus axis. Photo © Richard Barnes

Visitors enter each of these expansive galleries through portals of misty granite, and amble from one to another through smaller curated spaces. “I never fantasized that we could get a floor plate large enough to fit 95 percent of the galleries, but miraculously we did,” says Steward. In total, the second floor includes 32 display areas—the smallest being 144 square feet and the largest (the pavilions) being about 4,000 square feet. Gone are the bland white walls that abound in so much present-day museum architecture. Even the space dedicated to modern and contemporary art is a full-bodied ivory, akin to plasterwork. Wendy Evans Joseph, who worked on the exhibition design, collaborated closely with curators to develop color families and select fabric backdrops for the galleries—deep blues and blue-greens for European Art, lighter and jewel tones for American Art, and so on.

A perennial issue in museum design is balancing daylight and artificial light without damaging the objects on display. Five of the large galleries prominently feature V-shaped glue-laminated black spruce beams, 18 feet overhead and varying between 39 to 87 inches in depth, which conceal building systems and form coffers spanned by light-diffusing scrims. Above them, hidden from the visitor, is a 7-foot-tall attic, flooded by daylight introduced by an array of controllable solar tubes. “Museum buildings, in many ways, are like laboratories—dense with mechanical, electrical, lighting, A/V, and security systems that could easily overwhelm a space. At PUAM, we designed these systems to disappear into the architecture,” says Marc McQuade, a former associate principal at Adjaye Associates who had worked on the project from its inception.

The sprawling new structure allows the museum to exhibit about 5 percent of its collection of 117,000 objects (up from the previous 2 percent). Steward is proud of this achievement, considering the doubled square footage of the building and the more than doubled number of works on display. With rotations, that figure could reach 10 percent.

One of several so-called viewing rooms offers respite and glimpses of campus. Photo © Richard Barnes

Museumgoers are also bound to encounter, where lighting constraints permit, apertures with contextualizing views of campus. “One of my critiques of museum architecture is that it’s so interchangeable—that a museum could equally be in Berlin or Beijing,” Steward says. Especially inquisitive visitors are rewarded with the discovery of three “viewing rooms,” tucked into the corners of the museum. One such room surrounds visitors with faceted walls, while windows allow them to peer both toward campus and back into the entry court. Another, ringed by bentwood banquettes, features Jane Irish’s depiction of the cosmos overhead like a ceiling fresco.

A building, especially one as large and complex as this one, is never about a single person, even if the vision seems singular. Adjaye has said as much: “Architecture should have more weight to it than just being a series of signatures that become recognizable,” he told RECORD. Hundreds of people were ultimately responsible for PUAM’s realization. But it is also difficult to deny his hand, or to challenge the idea that his practice has recharted the course of contemporary museum design over the past two decades. This museum in particular does not take the lazy approach of letting the art “speak for itself”—PUAM is on par with the very collection it seeks to display. It is undeniably an exceptional work of architecture and a worthy addition to the pantheon of great American museums. So, who deserves the credit?

Editor’s note: The Princeton University Art Museum will open to the public on October 31.

Image courtesy Adjaye Associates

Image courtesy Adjaye Associates

Check back in November for other projects in our Colleges & Universities 2025 series.

Credits

Architect:

Adjaye Associates — David Adjaye, Joe Franchina, Daeho Lee, Rubi Xu, Paula Sanchez, Jaeyul Lee, Feras Alhabib, Lincoln Antonio, Ella Arne, Ryan Ball, Ivana Bogdan, Abraham Burrell, Darby Forman, Francesca Girardi, Celia Imrey, Alison Kung, Marc Massey, Marc McQuade, Tim Murphy, Kristen Newman, Justin Nguyen, Morgan Nonkululeko Mpungose, Kelsey Olafson, Joohui Son, Matthew Storrie, Can Vu Bui, Jamie Waxter, Kirsten Yaghoubi, project team

Executive Architect:

Cooper Robertson — Erin Flynn, partner in charge; Bruce Davis, Andrew Barwick, Wendy Cronk, Collin Gardner, Lloyd Helen, Mark Miller, Alban Denic, Andrea Solk, Alina Ahmad, Isil Akgul, Elizabeth Stoel, Devanshi Gajjar, Aidan Loweth, Iris Kim, Sumati Singh, Whitney Malone, Nathalie Guedes, Yuan Liang, Mohamed Mo-Alfy, Shalini Vimal, project team

Engineers:

Kohler Ronan (m/e/p); TY Lin (structural); Nitsch Engineering (civil); Carlin Simpson & Associates (geotechnical)

Consultants:

Field Operations (landscape); Heintges (facade); Tillotson (lighting); Studio Joseph (exhibition/casework design) Harvey Marshall Berling (AV/IT); Cerami (acoustics); Samuel Anderson Architects (conservation); Reg Hough Associates (concrete)

General Contractor:

LF Driscoll

Client:

Princeton University

Size:

146,000 square feet

Cost:

Withheld

Completion Date:

October 2025

Sources

Mass Timber:

Nordic

Cladding:

Madison Concrete, Bétons Préfabriqués Du Lac (concrete); AGM (metal panels)

Roofing:

Tremco, Sarnafil

Glazing:

Kawneer, Acurlite

Daylighting:

Solatube

Interior Finishes:

Goppion, Kubik Maltbie (casework); Click Netherfield (gallery display); Pyrok, Armstrong (acoustical ceilings); Kwik-Wall, Transwall (partitions); Redline & Redline, PDM (cabinetry); Benjamin Moore, Sherwin-Williams (paints); Patterson Flynn Martin, Warp & Weft, Nanimarquina, Swell (acoustical panels); Caesarstone, Richlite (solid surfacing); Bentley (carpeting); Roman Mosaic (terrazzo)

Lighting:

Marset, Nemo Lighting, Artemide, Litelab, Lutron