All eyes are on the government’s forthcoming climate competitiveness strategy

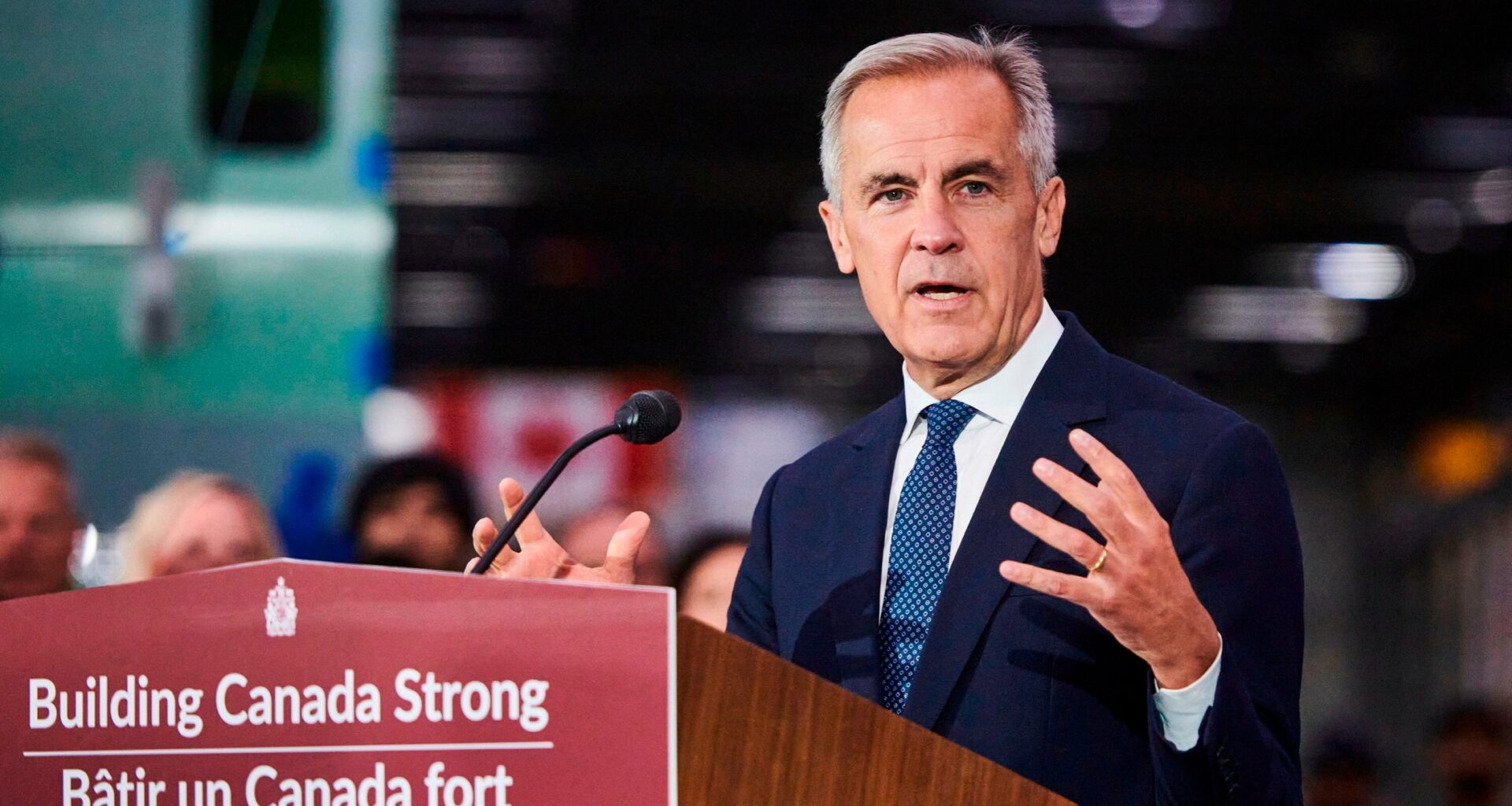

“I’m the same me,” Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney insisted during a podcast on October 16. With a five-year stint as the UN’s special envoy for climate change under his belt, Carney may be the most climate-aware world leader of all time.

Yet since becoming prime minister of Canada in January, he has pursued an “all of the above” approach to energy policy — appearing as open to building new pipelines as he is to strengthening the industrial carbon price.

Analysts say the former Bank of England governor and Financial Stability Board chair was elected largely under the impression that he was the right person to face down the threat posed by US President Donald Trump.

It is still early days, and leaders around the world would probably agree that dealing with Trump and his erratic approach to foreign policy is no picnic. But climate groups are becoming increasingly frustrated with Carney’s reluctance to defend Canada’s existing environmental regulations, or introduce new ones.

Strong climate chops

Caroline Brouillette, executive director of Climate Action Network Canada, tells Sustainable Views that Carney’s actions so far represent “either backsliding or sowing uncertainty around Canada’s climate commitments”.

“I think we have a prime minister who is slightly overconfident in his climate credibility. He believes that because of his reputation, anything he puts forward will be trusted,” says Brouillette. However, she adds, as the leader of “a network of nearly 200 organisations implementing and advocating for climate change, I can say that trust is eroding”.

Carney’s office is due to publish a much-anticipated climate competitiveness strategy ahead of the November 4 federal budget. It is expected the government will announce it around the G7 environment ministers’ meeting scheduled for October 30 and 31.

The broad expectation from those who have been involved in negotiations with the government is that its central policy tool for emissions reduction will be the national industrial carbon price, introduced in 2019. The prime minister’s office did not respond to a request for comment on what its strategy will address.

A confusing picture

One of Carney’s first actions on taking office was to abandon the consumer carbon price. In September he paused a mandate requiring Canadian automakers to ensure that electric vehicles made up a fifth of new car sales by 2026.

He has been open to the possibility of a new oil pipeline running from Alberta to British Columbia, and floated reviving the controversial Keystone XL pipeline in a discussion with Trump in early October.

“It’s always the same story — a pipeline is the solution to all of Canada’s ills,” says Brouillette. “Is that really where our imagination stops?”

Carney and his ministers have also declined to comment publicly on whether Canada will meet its Paris-aligned goal of cutting carbon emissions by 40 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030.

There is growing concern that the prime minister will next abandon the oil and gas emissions cap, which was due to be phased in between 2026 and 2030.

During the election campaign Carney said he would stick with the cap, which has faced strong opposition from energy companies. However, in October he told reporters its fate depended on other efforts to reduce emissions.

Courting oil and gas

Since being elected, Carney has also been criticised for giving oil and gas executives a disproportionate amount of his time.

He has consistently couched his language in terms of growth and economic development, and has vowed to make the nation an “energy superpower”.

In March, and again in September, dozens of oil and gas chief executives signed a letter to the prime minister with a number of policy asks. These include eliminating both the industrial carbon price and the emissions cap, shortening project approval timelines, and “simplifying” — or repealing — various other environmental regulations.

Speaking on a Bloomberg podcast on October 16, Carney said he was focused on policies that address climate change “while growing our economy”. He also reiterated his support for carbon capture and storage — interpreted by analysts as a nod to the oil and gas industry, which has invested in the technology.

In keeping with the “all of the above” approach, renewable energy investors are likewise “feeling fairly bullish about Canada’s investability”, says Fernando Melo, senior director of federal policy for the Canadian Renewable Energy Association.

He is encouraged by Carney’s close relationship with leaders in the EU, where the carbon border adjustment mechanism rewards countries with an effective carbon pricing system and a low-emissions grid. This puts Canada in good stead for a deeper trading relationship with the bloc.

Melo also points out that procurement is under way for an estimated 17 gigawatts of wind, solar and storage across the country, representing more than $31bn in potential investment.

What the private sector wants

Benjamin Bergen, president of the Council of Canadian Innovators, says that for Canada to shift away from its historical “rip it and ship it” extraction-focused economic model, the government needs to create policies that better support the commercialisation of new ideas.

“Innovators are looking for an industrial strategy that helps them turn good cleantech ideas into revenues, while retaining Canadian ownership,” he says. “And we have seen positive signalling [from Carney’s government] around intellectual property ownership in this country.”

The mainstream investor community is “quite happy” with how Carney is doing so far, Milla Craig, co-founder of capital markets advisory Millani, which regularly conducts investor sentiment studies, tells Sustainable Views.

Canada is, however, lagging behind other major economies on financial sector sustainability regulation. It does not have mandatory climate reporting, a taxonomy or labelling rules for ESG funds. These are all things investors would like to see, according to Millani’s September sentiment study.

A majority of investors interviewed over the summer expressed concerns that Canada is “falling behind its peers”, and that a lack of regulatory clarity risks weakening the country’s access to global capital.

“Investors recognise the challenge in front of Canada and believe [Carney’s] the right man for the moment,” Craig says. “That said, there is a growing echo of ‘but isn’t he the climate guy?’ The quietness [on climate] is a little concerning.”