Jimmy Batten has lived many lives. He was the British light-middleweight champion who went the distance with Roberto Durán, despite pre-bout warnings of brain damage. He was the boy whose infamous uncle was jailed after helping to wrap the body of the Krays’ victim Jack “The Hat” McVitie in an eiderdown and putting it in the back of a car.

After boxing he was a bouncer, singer and actor in The Bill and, ironically, Straker in the Nineties film The Krays. A CD of his pure crooner’s voice echoes around a one-bedroom flat close to the Dartford Crossing: “Yesterday is dead and gone, tomorrow’s out of sight.” Help Me Make It Through The Night is still Jimmy’s song.

Now 69, Batten was diagnosed with Parkinson’s eight years ago and has had dementia for the past four. He enjoys a dementia singing group and speaks in a hushed whisper, eyes lighting up as he rewinds past hard-to-find days to Durán, meeting Muhammad Ali and domestic scraps with Albert Hillman, Tony Poole and Larry Paul.

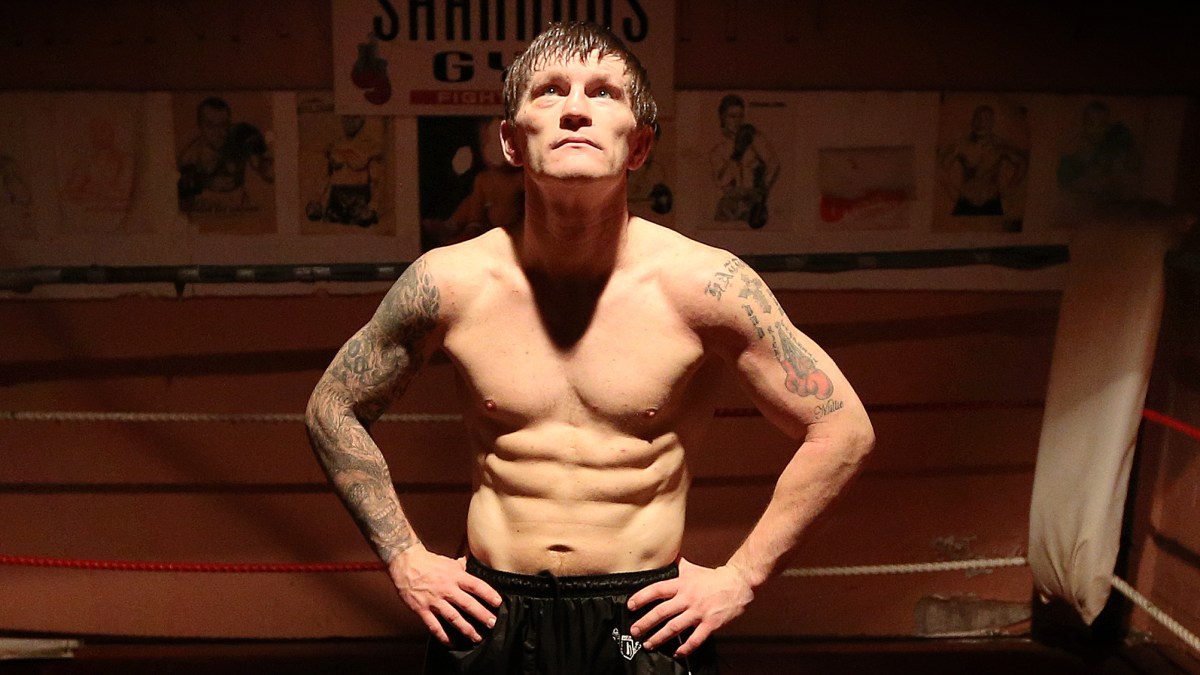

Batten in his prime as a young light middleweight and, below, at his south London home this week. The 69-year-old was diagnosed with Parkinson’s eight years ago and has had dementia for the past four

THE TIMES

TIMES PHOTOGRAPHER MARC ASPLAND

Batten and his partner, Jackie Harsant, are long-term supporters of the Ringside Charitable Trust, a small grant-giving and support organisation with a helpline manned by old boxers with the overarching aim of setting up a 36-bed care home for former fighters. Usually, Ringside toils away quietly, making piecemeal progress to little fanfare, but since the death of Ricky Hatton, the phone has been ringing a lot. Suddenly, the question of how to help old boxers with both physical and mental traumas is topical.

Dave Harris, a boxing man who used to work in social services, heads Ringside. In six years, they have raised about £300,000 and counselled hundreds of boxers, but they are miles away from the £1.5million they say they need to run a home for a single year. By contrast, the Injured Jockeys Fund, which relies entirely on donations and investment income to help past and present riders, has paid out £22million in grants since 1964 and set up three state-of-the-art rehabilitation centres.

Saudi money is inflating purses at the very top of boxing, but the trickle-down effect is a drought. Harris says: “We’ve had money quite often from ex-pros paying their £5 a month to get a home opened, but I get relatives of fighters with pugilistic dementia telling me it’s ridiculous they can’t get any respite care or support other than from Ringside. I say, ‘Well, it’s not like we haven’t tried.’ ”

Batten took Durán the distance in Miami in 1982 in a bout for which he received £5,000. Despite the Londoner holding his arms aloft, his illustrious opponent was given the unanimous points verdict

FOCUS ON SPORT/GETTY IMAGES

One man who did offer to help was Hatton himself. When he had an exhibition bout with Marco Antonio Barrera in 2022, he offered a percentage of his take, but Harris felt that, given the age of the fortysomething fighters, he could not morally accept it. “I thought, ‘What if something goes wrong?’ But God bless his heart.” Not long before he took his own life, Hatton got a lift with one of Ringside’s stalwarts from an old boxers’ function, and again said that he wanted to help.

By the River Thames, Batten tells me his Parkinson’s is a result of boxing, but he does not blame his profession. “I wanted to be a footballer, in the middle, but I’d do it all again,” he says. A born fighter, Jackie says he once dubbed an old acquaintance Dave the Coat-hanger, “because he’d say ‘hold my coat’ every time he went to have a fight”. Jimmy smiles. “Jackie’s my sparring partner now.”

It is hard, though. “Everything’s getting worse,” Jackie says. “There’s been a few falls. I’ve got to have an operation soon and I’ve got to find respite care somewhere. If they had a home, it would be great. They’d all be in there talking about boxing, bringing back memories. What’s he going to talk about if he goes somewhere else?”

Millwall-born Batten, who embarked on a career in singing and acting after his retirement from the ring, was inducted into British Boxing’s Hall of Fame in 2022

TIMES PHOTOGRAPHER MARC ASPLAND TIMES

He likes to talk about Durán. A year before the four-weight world champion fought Marvin Hagler in a Vegas mega-bout, he faced Batten in Miami in 1982. Incredibly, Batten had already been warned about brain damage. He broke three ribs in the fight but gave Durán a fright, although Batten says a deal had been done. “I’d been told I could not win before,” he says. He lost on points and was paid £5,000.

Old boxers do not suffer in a homogeneous way, but the risk of permanent brain damage is irrefutable. Way back in 1970, parliament debated a Royal College of Physicians report that stated 47 per cent of boxers who had fought professionally for ten years showed signs of brain damage. Others struggle without the buzz of fight night, the purpose of training or the loss of lifestyle.

Paulie Malignaggi, 44, is a former IBF world champion who won a bare-knuckle fight in the Leeds First Direct Arena on Saturday. Many will see his new venture as the trope of the old pro forced to come back, but the Italian American, fighting partly because he wants to move to Sicily, is good at articulating the problems of a fading spotlight. In Tris Dixon’s brilliant study Damage; the untold story of brain trauma in boxing, Malignaggi posited that depression and personality changes could be down to physical blows rather than the comedown of sporting afterlife.

Beaten by Hatton in Vegas in 2008, he tells me: “Boxers often come to it from a bad place in their life. Even if you’re middle-class, there’s something perturbing you that boxing fixes. When it’s gone, this crazy therapy is taken away from you, and you see fighters fall into these downward spirals.

“I definitely think more could be done in boxing, and life in general, with mental health, but I say that with an asterisk because we live in a time when victimhood is praised and a lot of people hog the help. Sometimes the ones who severely need the help don’t get it. Someone like Ricky would mention it here and there but would rarely complain. I don’t know how you get help to people who really need it. A lot of the time people are too proud to ask for it and that’s where they get hurt.”

Hatton’s death threw into sharp focus the lack of dedicated help available to veterans of a brutal sport

DOMINIC LIPINSKI/GETTY IMAGES

Malignaggi says he used to be “a prick” who would trash-talk opponents to fuel his fire, but he could not dislike Hatton. Indeed, Hatton would often get him tickets for Manchester football matches and offered to close his gym so Malignaggi could train for this month’s bare-knuckle bout. “The thing I regret is coming to the UK and thinking I should call him up, but then telling myself, ‘He’s Ricky Hatton, he’ll be too busy.’”

The Queensberry promoter Frank Warren, who knows more about boxing and mental health than most, agrees with Malignaggi. “You can’t force someone to sit there and bare their soul and talk about their demons,” he says. “They have to want to go through the process, and just because you’ve got money, it doesn’t mean you’re going to. My brother committed suicide. I don’t need anyone to tell me about what should be done because I should have been a bit more there for him. I was always too busy, and I think about that a lot. But how I choose to donate money is my choice.”

Warren has helped to raise over £10million for DEBRA, a research charity and support organisation for sufferers of a genetic skin disorder. “And we put a million quid into BoxWise, which has done more for knife crime through boxing than any other charity.”

Harris sometimes wonders whether there is “a boxing family” any more, and Warren recalls how people did not dig deep when MRI scans were introduced after the deaths of James Murray and Bradley Stone 30 years ago. “Do you know how many people in the whole of boxing put money in? Two,” he says. “One trainer put in £1,000 and I paid for every boxer in the country to have an MRI scan because you can’t say someone’s brain is deteriorating if you haven’t got a base to go from.”

Whatever anyone thinks about boxing, it is not going anywhere, so who can help? There is no world governing body like Fifa to take a lead, but one sanctioning organisation, the WBC, has its own mental health outreach programme and has a hardship fund that has dispensed more than $2.5million (about £1.9million) for things such as medical emergencies and funerals.

It is now planning to offer boxers expert investment advice through one of six companies. Its president, Mauricio Sulaimán, says: “When they make money, the last thing fighters want to do is save or invest. They don’t even want to pay sanction fees. It’s a huge problem and the more money they make, the more problematic it is.” Hence, the WBC will pilot a scheme next year where fighters must show they have a retirement plan.

Yet there is still a helpline adviser at Ringside who had to buy a tent out of his own pocket to help a homeless fighter, and with the former IBF world champion James DeGale, another to go bare-knuckle boxing, there are fears that combat sports are becoming more reckless, although Malignaggi claims no gloves and fragile hands mean there are fewer concussive combinations. “We are trying to make boxing safer, and you see bare-knuckle boxing, slapping competitions,” Sulaimán says. “It’s barbaric, beyond belief. All these different variations are only to feed the bloodlust of the current society. It’s boxing 120 years ago. How can governments allow this?”

Dana White, the UFC chief now involved in boxing, has been talking of having a smaller ring to encourage more blows. “I look at these people and they know f*** all about boxing,” Warren says. “They don’t know what a boxer goes through.”

It may well be that Ricky Hatton would have had his struggles in any life. Perhaps Jimmy Batten would have suffered from the neurodegenerative disease CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) had he pursued life as a Millwall footballer. In his flat by the Thames, his CD is still playing.

“Yesterday is dead and gone,” a younger Jimmy sings, and if it lives on in the pictures on the wall, a still from the Durán bout there and the Freedom of London certificate here, it still seems all too easy to be forgotten.