On a Monday morning in early January, the executives at Kingsdale Advisors were gathered for their weekly leadership meeting in their downtown Toronto office when sewage water suddenly began spilling out of the ceiling.

Buckets were placed around the room to contain the damage, but the space reeked like an outhouse. Kingsdale had to send everyone home, while a maintenance crew was called to investigate the problem.

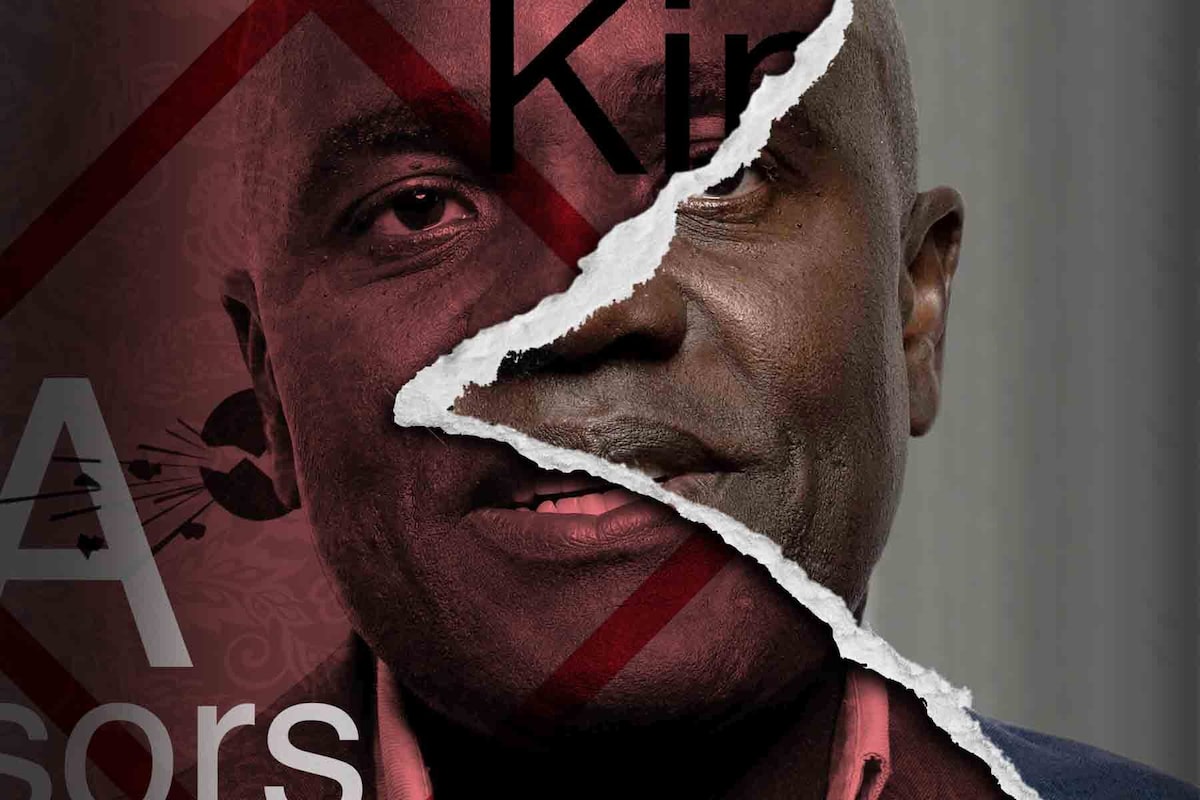

In a year full of setbacks, the leak felt almost too on-the-nose for the staff at Kingsdale, the shareholder advisory firm founded by the reigning King of Bay Street, Wes Hall, who is perhaps best known to average Canadians as one of the celebrity investors on the reality show Dragons’ Den. But he’s also the current chancellor of the University of Toronto, one of the most successful Black men in Canadian business and the founder of the BlackNorth Initiative.

Kingsdale has been battered by one blow after another: an exodus of executives, a lawsuit alleging a toxic work environment, a public loss in one of the most high-profile activist fights in recent history and growing signs that competitors are stealing the firm’s market share.

Launched in 2003, Kingsdale has been the dominant player in an important but niche industry on Bay Street. The firm is a proxy solicitor, meaning it’s hired by publicly listed companies (or activist investors) to win over shareholders. Proxy solicitors are involved in hostile takeovers, governance fights, mergers and acquisitions, and everyday annual general meetings.

Kingsdale has been so successful that Mr. Hall is often credited with elevating the entire industry, earning proxy solicitors a seat at the deal table alongside investment bankers and lawyers.

But recently, Kingsdale’s reign has been tested.

When Mr. Hall started Kingsdale, there was only one other proxy solicitor in town – his former employer, Georgeson Canada.

Today, the field is crowded, with about half a dozen other shops, including Laurel Hill Advisory Group, Sodali & Co (Canada), Carson Proxy Advisors, Shorecrest Group and Advisense Partners. U.S.-based Alliance Advisors has also made moves in Canada through the years. Most recently, it acquired Vancouver’s IR Labs in 2024. (One of the main players, TMX Investor Solutions, pulled out of Canada at the end of September, a company spokesperson confirmed – an indication of how tough the market is.)

Mr. Hall changed the game by expanding the service to include more strategy and governance advice. Kingsdale became experts in coaching clients on how to earn favourable recommendations from the big U.S. advisory firms, Institutional Shareholder Services and Glass Lewis. But the competition has since copied Kingsdale’s model. And they charge a lot less.

In April, Grant Hughes and Anna Fernandes, two former Kingsdale executives, launched a direct competitor after their departures: a proxy solicitation firm called Advisense Partners.Galit Rodan/The Globe and Mail

These were some of the challenges Kingsdale was already facing when, early last year, it ended up on the losing side of a vicious proxy fight between Gildan Activewear and U.S. investment fund Browning West.

Then, in the late summer of 2024, most of Kingsdale’s executive team – the chief executive officer, the president, an executive vice-president and two vice-presidents – walked out the door within a few weeks of each other. Mr. Hall went on damage-control duty, assuring clients that it was business as usual. He announced he would step into the CEO role himself, after spending years as the executive chairman.

But then one of those departed leaders, ex-president Grant Hughes, filed a wrongful dismissal lawsuit alleging Kingsdale had become a toxic work environment because of Mr. Hall. In a statement of defence, Mr. Hall denied the claim and accused Mr. Hughes of being the “architect of his own departure,” but the lawsuit was notable in that it brought into the open an allegation that had been quietly discussed in the industry for years: that working for Mr. Hall was not easy.

Tensions escalated further in April, when Mr. Hughes and another departed executive, Anna Fernandes, launched a competitor to Kingsdale: a proxy solicitation firm called Advisense Partners. Kingsdale has filed for an injunction and sued the pair for breach of contract. In the claim, which has not been tested and a statement of defence has not been filed, the firm accused the ex-executives of stealing proprietary information.

If all of that wasn’t enough, another of Mr. Hall’s businesses, QM GP, an environmental services company, was put into creditor protection in August. QM asked a judge to approve a $14-million interim financing loan agreement from WeShall Investments, Mr. Hall’s namesake private equity firm, which holds 90 per cent of QM’s common shares.

For the past year, The Globe and Mail has documented the challenges at Kingsdale. Through interviews with more than 40 central figures in Kingsdale’s rise – including former Kingsdale and WeShall employees, clients, competitors, and Bay Street lawyers – as well as a review of thousands of pages of legal documents, a picture has emerged of a company, an industry and a man at a crossroads.

The reporting sheds new light on Mr. Hall’s exit from Georgeson Canada, friction during the Canadian Pacific Railway proxy battle that made his career and what it’s actually like to work at Kingsdale.

On two recent September mornings, Mr. Hall agreed to a pair of brief but wide-ranging interviews.

“Our clients expect the best from us,” Mr. Hall said. “You’re working on high-stakes situations… The standard here is extremely high and it will always be extremely high.”

With respect to his executives leaving, Mr. Hall said that they each left for their own reasons. One, Kelly Gorman, become the CEO of Advocis, and others started their own businesses.

He rejects the notion that Kingsdale is slipping behind its competitors, but he also acknowledges that with a more crowded field, the firm can’t afford to become complacent.

“We don’t know when the next deal is coming. And now we have, like, 10 players in the space,” Mr. Hall, 56, said. “We have to go out and fight for every single deal and because of the fact we charge so much more than everybody else, we have to show every single deal we go on that we’re better.”

When Mr. Hall started Kingsdale in 2003, there was only one other proxy solicitor in town. Today, the market is crowded, and the competition has since copied Kingsdale’s model.Wade Hudson/The Globe and Mail

A credenza behind Mr. Hall’s desk at Kingsdale showcases family photographs and shots of Mr. Hall alongside notable figures, including Princess Anne. But there’s also a picture, positioned front and centre, of the tin shack in rural Jamaica where Mr. Hall grew up.

It’s a reminder – to himself and anyone who visits – of how hard he has had to fight to get to where he is today.

Mr. Hall’s remarkable story has been immortalized many times in articles, as well as in a feature-length documentary and his best-selling memoir, No Bootstraps When You’re Barefoot.

Born into poverty, Mr. Hall emigrated to Canada as a teenager to live with his father. He worked in a law firm’s mailroom and attended night classes at George Brown College to earn his law clerk certificate. This led to a job at CanWest Global Communications and then, in 1998, Mr. Hall moved to CIBC Mellon, which is where he learned about the proxy solicitation business.

At the time, CIBC Mellon was a transfer agent, which performs tasks such as maintaining a company’s shareholder investment records and scrutineering its AGM. Because of the nature of the work, transfer agents were in regular contact with proxy solicitors.

In this period, Mr. Hall started to build his network, which today is the envy of Bay Street. He stood at the registration desk at AGMs and greeted CEOs, board members and investors, dazzling everyone with his warmth, smarts and confidence. He collected business cards and scribbled notes to himself on the back about each person.

It was through his work at CIBC Mellon that Mr. Hall met Glenn Keeling, the CEO of Georgeson Canada.

Georgeson & Co. was founded in New York during the Great Depression and in 1999, it was acquired by Shareholder Communications. This new business wanted a Canadian office and tapped Mr. Keeling, a gregarious salesman with a mop of orange hair, to run it. Mr. Keeling was impressed by Mr. Hall and offered him a job as vice-president of business development. While Mr. Hall didn’t know much about being a proxy solicitor, by 2002, he was a top performer.

One industry veteran said that Mr. Hall was a phenomenal salesperson with an almost supernatural ability to read people. If someone isn’t buying what he’s selling, he can pivot on the spot, they said.

In those days, Mr. Hall’s office was beside Mr. Keeling’s. Around the corner was a bank of desks where David Salmon, Christine Carson and Susy Monteiro sat. (Penny Rice came on board a couple of years later.) People who know the proxy solicitation industry will recognize these individuals as the current chief executives of Laurel Hill Advisory Group, Carson Proxy Advisors, Sodali & Co (Canada) and the Shorecrest Group.

Christine Carson, founder and CEO of Toronto-based Carson Proxy Advisors, a Kingsdale competitor.ALEX FRANKLIN/The Globe and Mail

But back then, Georgeson had no competition and business was booming. Still, behind the scenes, tensions emerged between Mr. Keeling and Mr. Hall.

“One of the problems that my boss, Glenn Keeling, had with me was: I was – he claimed – a good salesman and I was distracted because I was working on client files,” Mr. Hall said. Mr. Hall didn’t want to just get clients through the door and then pass them off to the operations team. He wanted to work with them.

Things blew up after Mr. Hall landed a client that Mr. Keeling had also pitched. Shortly afterward, Mr. Hall was at a conference with Thomas Kies – the parent company’s executive vice-president – and asked for a private word.

“He tells me he wants to run the business,” Mr. Kies recalled. “I was blown away. Blown away in a good way. Somewhat negative at first, like, ‘Are you kidding me? You just started,’ but appreciative of the entrepreneurial spirit.”

Mr. Kies says he told Mr. Hall that while he respected his ambition and contributions, Mr. Hall was still new. In Mr. Kies’s telling, Mr. Hall was respectful, but indicated that if Georgeson didn’t make him CEO, he would leave.

“Sure enough, he left,” Mr. Kies said. “And we’re all very proud of him. He’s a great graduate of Georgeson U.”

Asked about those days at Georgeson and his relationship with Mr. Hall, Mr. Keeling said: “My time with the team at Shareholder Communications and Georgeson was the best of my entire career. We had the most fun. We wrote the most contracts. We pioneered modern day proxy solicitation. And I think the rest of the industry is benefiting from that today.”

For his part, Mr. Hall says he doesn’t remember this conversation with Mr. Kies. He insists he had no interest in the CEO job. (Mr. Kies was surprised to hear Mr. Hall deny the conversation.)

What did happen, Mr. Hall said, is that he tried to convince head office that Georgeson needed to change its business model.

Proxy solicitors have to think about three types of investors, Mr. Hall explained. There are registered shareholders, who buy directly with the company and whose names are available, and then the folks who buy through a financial intermediary. These investors are divided into two groups: the non-objecting beneficial owners (NOBOs) – whose identities are known – and objecting beneficial owners (OBO) – who opt to keep their information private.

“Georgeson was focused on calling the non-objecting owners and the registered owners,” Mr. Hall said. But they don’t swing votes. The power was with the OBOs, which is often where big institutional investors can be found.

Identifying OBOs wasn’t impossible, it just required logic and legwork, such as contacting investors who are known to be interested in certain industries or funds, checking in with portfolio managers or cross-referencing with the big institutional investor’s public fillings.

But Georgeson wasn’t interested.

So Mr. Hall decided to build this new business himself.

Wes Hall at his Toronto home in June, 2020. To this day, one key to Kingsdale’s success has been Mr. Hall’s relationships with the big corporate law firms.Fred Lum/the Globe and Mail

Around this time, Mr. Hall was at the gym chatting with an acquaintance about his idea for a new kind of proxy solicitor. That man, Peter Notidis, was the chief financial officer at a financial services business called Kingsdale Capital. Mr. Notidis connected Mr. Hall with the company’s co-founding partner, Joseph Duggan, who recalls being very impressed with Mr. Hall: “He was extremely bright and passionate.”

They made Mr. Hall an offer. For 25 per cent of Mr. Hall’s company, Kingsdale Capital would give Mr. Hall an office, access to the Kingsdale name and support services. Even though there was no financial investment, Mr. Hall thought the legitimacy a Bay Street address would carry was worth it. He took out a $100,000 loan and incorporated Kingsdale Shareholder Services (its then name) in June, 2003.

Mr. Hall remembers showing up at Kingsdale Capital’s office on his first day. A receptionist led him down a classically decorated corridor, past wood panelling and mahogany-hued desks, to his space: a tiny office in a back hallway, where the walls were fluorescent yellow.

“At the end of the day, it didn’t matter to me, because when I was bringing clients in, I brought them into the fancy boardroom,” Mr. Hall said. “Nobody would know that I’m in this dungeon in the back.”

Mr. Hall phoned everyone he knew, especially Bay Street lawyers, who have influence over whether their clients hire a proxy solicitor. It was through a contact at Cassels Brock & Blackwell that Kingsdale landed its first client, Vector Aerospace.

To this day, one key to Kingsdale’s success has been Mr. Hall’s relationships with the big corporate law firms. This is especially true with respect to Norton Rose Fulbright, whose chair – Walied Soliman – has become one of Mr. Hall’s closest friends. They are also business partners. Corporate filings list Mr. Soliman as the president of 2539593 Ontario Inc., which owns 10 per cent of QM GP’s common shares. The ties between the two men are perceived to be so strong that some Bay Street lawyers say they have become wary of referring work to Kingsdale, because they worry the firm is too loyal to Norton Rose.

Kingsdale’s head of communications, Aquin George, said in an e-mail: “Our relationship with Norton Rose is no different from those we maintain with many leading firms across the market.” Mr. Soliman declined an interview request.

Soon Mr. Hall landed other clients, such as Leitch Technology. He beat Georgeson Canada in that fight. Kingsdale hiked its prices, and clients were willing to pay because Mr. Hall had developed a reputation for winning. According to Mr. Hall’s memoir, after his third year in business, he had 20 employees and was doing more than $7-million in revenue.

Other people took note of Kingsdale’s success. Some Georgeson staff – including Mr. Keeling, Mr. Salmon and Ms. Carson – left to launch Laurel Hill Advisory Group. (Georgeson closed its Canadian office in 2015.) Meanwhile, Mr. Hall bought out Kingsdale Capital’s stake in his company.

Ms. Carson said that Mr. Hall had three things going for him: his sales chops, his connection to lawyers and his timing. Kingsdale launched at the same time that the Canadian stock market started to see more activism. And the turning point came in 2011, when Pershing Square Capital Management, the American activist hedge fund headed by Bill Ackman, went after CP Rail.

American hedge fund manager Bill Ackman, the founder and CEO of Pershing Square Capital Management.PATRICK T. FALLON/AFP/Getty Images

Pershing Square’s play to reshape CP Rail’s board and management was audacious. Its board included some of the biggest names in Canadian business, including former Royal Bank of Canada CEO John Cleghorn, Suncor Energy CEO Rick George and former deputy prime minister John Manley.

Mr. Ackman retained law firm Davies Ward Phillips & Vineberg, which advised Pershing Square to hire Kingsdale. Against the odds, Mr. Ackman won.

The moment was a wake-up call for boards. If CP Rail’s blue-chip team of directors could fall, everyone was vulnerable. For Kingsdale, CP Rail was a breakthrough moment. The win became central to Kingsdale’s marketing and as the years went by, the chatter on the street was that Mr. Hall had been Mr. Ackman’s secret weapon.

But the truth, say four people involved, is that Kingsdale and Mr. Hall played a more modest role. And in fact, some of the firm’s duties on the file were reassigned due to a “competence” issue. At one point, a problem arose with its call-centre work.

“Wes did a great job, a superlative job,” said one source, who could not be named as they are not authorized to speak about the deal. “But there were some issues.” For example, they said, another problem – which was not Kingsdale’s fault – was that Pershing Square realized late in the process that many of CP Rail’s most important shareholders were American, which Kingsdale was not in the best position to go after. Pershing Square shifted this work to its American proxy solicitor, D.F. King.

Another source said that they recall criticism of Kingsdale, but that it may not have been warranted. Pershing Square was a demanding client.

When asked about the CP Rail deal and Kingsdale, Patricia Olasker, who was Davies’ lead counsel, said: “We are big fans of Kingsdale and they remain No. 1 in the market.”

Asked about the allegations that Kingsdale had performance issues on CP Rail, Mr. Hall said: “Not to my knowledge.” He added “but they paid us 100 per cent of the fees and they gave us credit for the win.”

In every proxy fight “there’s always stress, and at the end of the day, people always say, ‘Well, maybe you should do more, maybe you should do less,’” Mr. Hall said. “It’s about the results.”

Regardless of what happened behind the scenes, Kingsdale became unstoppable.

Around this time, there were media reports that Kingsdale was involved in 85 per cent of the country’s proxy battles. According to two former Kingsdale employees, the firm’s profit margin was hovering around 70 per cent. (In recent years, profit margins have typically been in the mid-50s.)

At this peak, Mr. Hall sold a majority share of Kingsdale to MDC Partners in 2014 for a rumoured sum of about $50-million. (Several years later, after MDC hit financial troubles, Mr. Hall bought the company back for a fraction of the cost.)

The next decade marked Kingsdale’s golden age.

Jonathan Pinto was running D.F. King Canada (it later evolved into TMX Investor Solutions) in 2019. He said pitching against Kingsdale was a constant struggle.

“Kingsdale and Wes are synonymous with the industry,” Mr. Pinto said. “I literally would be talking to a CEO, who had no knowledge of proxy solicitation, and I’d start to talk about what we do and he’d say, ‘Oh yeah, like Kingsdale.’”

But recent data suggests that may be changing.

Assessing market share in the proxy solicitation business is difficult, because so much of the work is never publicly disclosed. But there are some indications that the landscape has shifted.

The Globe assessed thousands of public record filings on SEDAR+ in the years 2020, 2023 and 2025 (up to October 10) to determine how many clients each dominant proxy solicitation firm – Kingsdale Advisors, Laurel Hill Advisory Group, Carson Proxy Advisors, Sodali & Co (Canada), Shorecrest Group and TMX Investor Solutions – was working for in a given year. The analysis was conducted using a keyword search of various documents, including news releases, circulars and proxy forms, and then a manual verification. (In 2020, Sodali & Co (Canada) and TMX Investor Solutions were not players in the Canadian market. Instead, The Globe searched Gryphon Advisors, which became Sodali in Canada, and D.F. King Canada, which became TMX Investor Solutions.)

Five years ago, of 167 identified mandates, Kingsdale secured nearly half – 44 per cent – of the work, while Laurel Hill was on about 32 per cent of the files and Sodali 11 per cent. But the data suggest Kingsdale’s market share has been falling ever since. And so far in 2025, of the 155 identified mandates, Kingsdale is only acting in a quarter of them, while Laurel Hill is now the dominant player with 42 per cent.

Bloomberg also tracks the market through its Global Activism League Tables. Kingsdale has ranked as Canada’s No. 1 proxy solicitor on the company-representation side for years — there is a separate ranking for activist-side mandates, which Carson Proxy dominates — but in 2024, Kingsdale fell behind Laurel Hill. The firm returned to the top spot in the first half of 2025, but this isn’t a complete picture of market share. Carson Proxy, Laurel Hill and Sodali are each ranked on both the activism and company assessments, but Kingsdale is only displaying company work.

Mr. Hall said in an email that since so many of their mandates are not publicly disclosed, SEDAR is not a good metric: “We are on pace to have our best year in the history of the company both in revenue and number of engagements. So I can unequivocally tell you that this business has never been stronger.”

Still, the SEDAR statistics coincide with what industry experts and lawyers say is a general trend: Companies are increasingly hiring Kingsdale’s competition.

One senior Bay Street lawyer said that Kingsdale does good work, but so does everyone else. This wasn’t the case a decade ago, they said.

Part of the issue is the cost.

Kingsdale created a playbook that the competition emulated and now offers at a discounted price. Also, the service has become largely commoditized. For example, today, unlike 20 years ago, there are a multitude of shareholder intelligence databases that make identifying OBOs much easier.

And it’s not just the upfront costs.

Kingsdale’s success fees have come up in numerous cases of litigation through the years, including a recent blockbuster judgement in which Sprott Asset Management was ordered to pay Kingsdale a success fee of more than US$4.6-million. This was despite the company’s assertion that, months after retaining Kingsdale, Sprott decided to go in a different direction. Sprott claimed that Kingsdale did no material work on the file for more than a year before Sprott closed its deal. “The Claim is an improper attempt by Kingsdale to obtain payment for work that it did not perform,” read Sprott’s statement of defence.

But the judge concluded that Sprott choosing to shut Kingsdale out did not sever the link between Kingsdale’s services and the ultimate transaction. The matter is being appealed.

From left, reinstated Gildan CEO Glenn Chamandy, chairman Michael Kneeland and Browning West partner Peter Lee speak to the media following the company’s annual meeting in Montreal, in May, 2024.Christinne Muschi/The Canadian Press

One of the starkest examples of the pricing disparity between Kingsdale and the competition occurred with the Gildan proxy fight.

In December, 2023, Gildan’s board shocked investors by firing long-time CEO Glenn Chamandy. Immediately, one of the T-shirt maker’s largest shareholders, Browning West, launched a campaign to get him back. Gildan’s board hired Kingsdale and the law firm Norton Rose to help it win. The battle was messy, with each side accusing the other of underhanded tactics. But the following May, it was a resounding victory for Browning West and Mr. Chamandy was reinstated

Kingsdale sent Gildan an invoice for $2,343,736.78. (The fee became public because Gildan refused to pay and Kingsdale sued. A Gildan spokesperson said all outstanding invoices have now been paid and the lawsuit is resolved.) It was a figure that raised eyebrows. Several lawyers and shareholder advisers told The Globe that they believed that Gildan should have been encouraged to settle early on, because it was obvious the board had misjudged the shareholders. Then word got out that Browning West’s proxy solicitor, Carson Proxy, had only billed about $500,000 – for its win.

This is the other factor at play: the increased competition.

While the Gildan win put Carson Proxy on the map, Ms. Carson has long been known as a quiet killer in the industry – when activist investor Simpson Oil Ltd. successfully went after the board at Parkland Corp. earlier this year, it hired Carson Proxy – who does great work for a comparatively low price. Carson Proxy has been Bloomberg’s No. 1-ranked proxy firm in Canada on the activist side since 2022.

Asked about her fees, Ms. Carson says she knows she’s undercharging: “When I get the call, I have fear of missing out. I price it because I want to make it as easy as possible for them to say yes because I want to work on this… I love the competition that proxy battles bring. The strategy. The tactics.”

Laurel Hill’s CEO, Mr. Salmon, says he believes one of the reasons clients have gravitated toward his firm is its stability. There’s been zero turnover at the executive level in more than a decade, he said, and there’s very strong retention at every level. In a knowledge-based business, this kind of continuity is invaluable, he said.

“We don’t lose a lot of people and that goes to the culture,” he said.

Which comes to the final reason that industry experts have said Kingsdale is no longer the undisputed leader: its culture problem.

David Salmon, CEO of Laurel Hill, at his home in North Vancouver, B.C.Jennifer Gauthier/The Globe and Mail

The Globe has interviewed 16 Kingsdale alumni about their time at the firm. Many describe an exciting work environment that was also a meat grinder.

The days are long – often nine or 10 hours in slow periods, and easily stretching to 14 hours a day during proxy season, plus weekends – and stressful. For the amount of work and pressure, the compensation was also not great, staff said. While executives were reasonably well paid, that was not the case for more junior staff. Analysts come in at around $55,000 per year, while a director might start at $70,000 – a challenging wage to live on in Toronto and commuting was difficult because of the long hours. Mr. Hall does not like staff working remotely.

Former staffers say that Mr. Hall’s philosophy was to start people off lower on the pay scale and then make them prove that they were worth more. For those who stayed, there were often raises and promotions of several thousand dollars per year over the first three or four years.

Some Kingsdale alumni said they didn’t mind the slog. Getting a chance to work with the biggest companies on some of the most flashy files on Bay Street – and with Mr. Hall – was priceless experience.

But it wasn’t for everyone.

Bernard Simon worked for Kingsdale for a year as a vice-president of communications in 2012. Mr. Simon said Mr. Hall is a brilliant man and he learned a lot, but he decided to quit after only a year.

“I left because, how do I put it, it was very stressful… He was not, in any way, a warm, fuzzy, compassionate type of boss.”

Mr. Simon says he remembers sitting on the subway on the way to work, waiting in dread for the train to surface and catch a signal again, “so I could look at my BlackBerry and see what Wes was urgently wanting from me,” he said. Requests would come at any hour and on weekends. The turnaround times were almost always tight, sometimes unnecessarily so, Mr. Simon said.

Other staff say that one day, Mr. Hall would tell them they were amazing, and then suddenly, something would change. He would become cold and stop replying to their e-mails or giving them face time. (Asked about this, Mr. Hall said: “I guess that’s how people feel. It’s unfortunate.“)

In Mr. Hall’s view, everyone was replaceable, so he wasn’t concerned if people were unhappy, three former Kingsdale staffers said.

Many of those interviewed said that the dynamics around race were not lost upon them. Mr. Hall is one of the most successful Black men in the country. Would things feel differently if he was a difficult white boss? He was also a person who had overcome incredible obstacles. Even those who had negative experiences working at Kingsdale said it was impossible not to respect what Mr. Hall had accomplished in business and for the Black community.

Still, the culture at the company has been challenging throughout its existence, even in periods when Mr. Hall was not involved in the day-to-day operations.

In 2017, Mr. Hall stepped back from the chief executive role and named Amy Freedman as his successor. Mr. Hall took the title of executive chairman and then turned some of his attention to his other business ventures. As chairman, Mr. Hall mostly dealt with Kingsdale’s senior leadership, but staff say the tone of the organization still came from the top. (Ian Robertson took over after Ms. Freedman left in 2021. He was among the executives to quit in 2024. Shortly after his departure, he launched a leadership advisory firm called the Jefferson Hawthorne Group.)

Ian Robertson, one of the Kingsdale executives to quit in 2024, launched a leadership advisory firm called the Jefferson Hawthorne Group shortly after his departure.Christopher Katsarov/The Globe and Mail

Retention has been another perennial problem at Kingsdale, especially in recent years.

So far in 2025, Kingsdale (which shares some senior staff with WeShall) has lost its CFO, the head of human resources, Mr. Hall’s chief of staff, its general counsel, the operations manager, two other executive vice-presidents and a director – among others.

Staff say the firm could be callous.

In one example, which is detailed in court records, a former vice president of finance at Kingsdale sued the firm for wrongful dismissal after he was allegedly fired after disclosing a cancer diagnosis.

According to a statement of claim, Brian Ilavsky informed his employer on Feb. 27, 2012, that he had been diagnosed with stage 4 colon cancer. “On Wednesday, February 29, 2012, Mr. Hall met with Mr. Ilavsky and terminated his employment.” A termination letter was couriered to Mr. Ilavksy’s home the next day. In the lawsuit, Mr. Ilavsky said Kingsdale’s actions “detrimentally affected Mr. Ilavsky’s ability to cope with and recover from his current health diagnosis.”

In a statement of defence, Kingsdale asserted that there had been problems with Mr. Ilavsky’s performance and, despite coaching, things did not improve. Kingsdale said that Mr. Ilavsky was informed on Feb. 13, 2012, that “his employment would be terminated.” The firm had no knowledge of his medical issues, the document read. In response to these allegations, Mr. Ilavsky’s lawyer rejected this narrative. The former finance executive died in July, 2014, but Kingsdale continued to fight his widow in court. The matter eventually settled for an undisclosed sum.

Kingsdale is also known for sending legal threats to departing staff, which have accused them of stealing the firm’s confidential information or violating an aspect of their employment contract by taking on a new role. The Globe has viewed two such letters and been told details of another, the specifics of which cannot be divulged because of the nature of how the matters were resolved.

Asked about these threats, Mr. Hall said it’s standard practice in business to protect propriety information and that while the firm has defended itself in court, “we have not launched lawsuits against employees for leaving the firm ever.”

However, in 2022, Kingsdale sued its former CEO, Ms. Freedman, for $8-million about a year after she left the company. Ms. Freedman had taken a job with Ewing Morris & Co. Investments Partners, which ended up in a proxy contest with Kingsdale client, First Capital REIT. Mr. Hall accused Ms. Freedman of using confidential information she had obtained while at Kingsdale against its client. The matter was resolved confidentially.

Ms. Freedman declined to comment on the lawsuit.

Bilal Khan, who had been the managing partner of WeShall, until he left last month, said Mr. Hall is simply misunderstood.

“Obviously he has a reputation. And it’s true: Wes is exceptionally demanding. He’s, in many ways, a perfectionist…I don’t think you get to a place where Wes has without that kind of work ethic. He’s the first person in. The last person out,” Mr. Khan said. “He is very tough to work with. To work for. He has very high expectations. But personally, just me, it’s what I respect about him the most.”

Mr. Khan says the only reason he left WeShall was because of the problems at QM GP, which were going to require the business’s full attention. He wanted to focus on doing new deals.

One former senior Kingsdale staffer who, like Mr. Hall, is a Black man said he’s heard some of the criticism of Mr. Hall. But to him, it’s clear that Kingsdale’s founder is being held to a different standard.

There are plenty of successful white men on Bay Street who can be demanding leaders.

“No one questions them and how they make money. Or who they burned to get where they are.”

In July, 2024, a frustrated Mr. Hall held a meeting with his leadership team.

“Who thinks this can be a $50-million business?” Mr. Hall asked the group. (Kingsdale was reliably doing about $20-million in annual revenue, according to company sources.)

Newer executives put their hands up. But those who had been around longer, were hesitant. They told Mr. Hall that the metrics weren’t there. The market was saturated with competition and the business was changing. The work was commoditized and clients were no longer willing to pay as much for services.

Mr. Hall accused the executives of being negative and insisted they push forward with the plan. This meeting, according to sources in the room, convinced some of the since-departed executives that it was time to leave. They worried they were being set up to fail.

Yet WeShall’s Mr. Khan was also in that meeting and he doesn’t think Mr. Hall’s goal was off base. He thought some of the executives’ pushback around fees was misguided: “I think they were looking at the wrong metric. They have Wes Hall at the helm. Wes can command a different premium than what I think most people can.”

Mr. Hall has the magic touch, Mr. Khan said.

“I would never bet against Wes Hall.”