I’ve been researching and writing about nuclear war—its history, politics, science, and strategy—for more than 40 years. None of the many books and films that I’ve consumed on the subject have filled me with such overpowering dread as Kathryn Bigelow’s new movie, A House of Dynamite. It is very realistic, and thus by definition frightful.

Dr. Strangelove, still the genre’s masterpiece and extremely realistic in its detail (Daniel Ellsberg, then a Pentagon staffer, told a colleague after they watched it in a theater, “That was a documentary!”), filtered its dread through caricature and satire. Fail Safe, which came out the same year (1964), was didactic and clinical. There was one hair-raising moment in The Day After (a 1983 TV movie), the scene where a dozen intercontinental ballistic missiles blast out of their silos in eastern Kansas and head toward their targets across the world in the Soviet Union. No one had ever seen a picture like this. I remember thinking, “Holy shit, this is what it will look like.”

I had a similar thought several times while watching A House of Dynamite—this is how it could very well happen, how the people at the top will act, think, and feel.

What follows is not a movie review, though I agree with Slate’s Dana Stevens, among many other critics, that this is a brilliant piece of filmmaking. Instead, I’m going to discuss whether the film’s plot points, scenes, and ambience are plausible. So, consider this a big spoiler alert.

Maybe watch the movie first (it premiered today on Netflix), then go back and read this afterward.

The film’s premise is no secret by now. Early-warning radars detect a ballistic missile heading toward Chicago. It seems to have been launched by a submarine, so it’s unclear whose missile it is—Russia’s, China’s, or North Korea’s—or whether its launch was deliberate or accidental. Over the next hour or so, the film darts back and forth between a few groups of players—the missile-defense crew in Alaska, the secretary of defense and the general in charge of Strategic Command, the deputy national security adviser who runs communications with the Russian foreign minister, and finally the president (who hears of the attack while at a packed auditorium honoring a girls’ basketball program) and the officer escorting him with the nuclear suitcase who walks him through the various options for retaliation.

Now come the spoilers.

The film’s first tense moment comes when the top general at StratCom realizes this is a real attack. He and several other top officials (the secretary of defense, the intelligence chief, and others) have assembled in a secure conference call. You might wonder why everyone behaves so casually, talking about last night’s ballgame and other mundanities, until they realize they’re watching a real attack in progress. It’s because these conference calls happen a lot. For instance, a call is organized every time North Korea prepares to launch a missile, because nobody knows whether the missile is armed, or whether the launch is a test or the beginning of an attack. During President Trump’s first term, conference calls like this were held at least 15 times to monitor a North Korean missile launch. President Trump was never asked to join in—it soon became clear that the launches were just tests—but Secretary of Defense James Mattis had been given the authority, if he thought the launch was aggressive, to fire conventionally armed ballistic missiles (called ATACMS, based in South Korea) at the North Korean launch site—a move that would probably kill North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un, who often attended such launches. It was assumed that this could well be the first step in a spiraling escalation to a major war.

Another purpose of the conference calls—which often involve several Cabinet secretaries—is to keep officials on their toes, to routinize the steps that would have to be taken, and to keep the players from flailing in panic, if the attack on the radar screens turned out to be real. One message of this film is: Good luck with that.

At this point in the plot (as would happen in real life), the missile-defense crews in Alaska launch a Ground-Based Interceptor to shoot down the missile as it arcs above the atmosphere. The crew members, like all the other advisers and technicians in the nuclear enterprise, perform professionally. But the first GBI fails to separate from its rocket booster. Then the second GBI misses the target. After that, the missile enters into its “terminal phase,” plunging back into the atmosphere, darting toward Chicago—and there’s nothing that anyone can do about it.

How real is this? Alas, very. In the movie, as the GBIs are fired at the target, the secretary of defense asks the deputy national security adviser whether these interceptors work. The young adviser replies that the task is like “hitting a bullet with a bullet.” In tests, he goes on, they’ve hit the target just 61 percent of the time—if they first successfully separate from the rocket (and, as the film correctly dramatizes, sometimes they don’t separate). The defense secretary is outraged. “It’s a coin toss?” he shouts into the phone. “That’s what we’ve got for $50 billion?”

I felt like yelling back at the screen, “No, that’s what we’ve got for $500 billion!” That’s about how much we’ve spent on the strategic missile-defense program since President Ronald Reagan started it in 1983.

Otherwise, yes, this too is accurate. The tests in real life succeed about half the time—and the people conducting those tests have a lot of time (days, even weeks) to plan them; everyone knows where the mock warhead is coming from, where it’s going, and so forth. A 50-50 record is remarkable for hitting a bullet with a bullet (which is what this weapon sets out to do), but it’s woeful if the downside of that 50-50 means Chicago gets blown to smithereens.

Finally, there’s the ultimate chapter in this tale—what does the president do? Many people still don’t realize it, but the president has the sole authority to order the launching of nuclear weapons, in response to an attack, in preemptive anticipation of an attack, or for whatever reason he wants. He is followed all the time by an officer with a heavy suitcase—the so-called football—that contains communications gear and a black book describing all the attack options. When the president makes his decision and authenticates his identity, the officer sends the code to the National Military Command Center in the Pentagon, where a one-star general, who has been vetted for compliance, passes on the order to the launch crews at the ICBM silos, inside the ballistic-missile submarines, and on the bomber aircraft bases. The officials on the conference call can give advice, but only the president gives the order.

In the summer of 1974, amid numerous reports of President Richard Nixon’s frequent stress and drunkenness under the pressure of Watergate and his imminent impeachment, Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger secretly asked the Joint Chiefs of Staff—the nation’s top military officers—to call him if they received any “unusual orders” from the White House. In doing so, Schlesinger was asking the generals to commit an act of extreme insubordination (neither he nor the chiefs were, or are, in the nuclear chain of command), but if something weird had happened and if the chiefs had gone to Schlesinger before following the president’s order, it would also have been an act of highly patriotic—possibly world-saving—insubordination. (Schlesinger, who died in 2014, denied this story in a 2008 Oral History interview with the Nixon Library, but he told me it was true when I interviewed him in 1982 for my book The Wizards of Armageddon, and it has since been confirmed in an article by a prominent attorney who was discreetly shown Schlesinger’s memo at the time of the crisis, when he was an Army lawyer working in the Pentagon.)

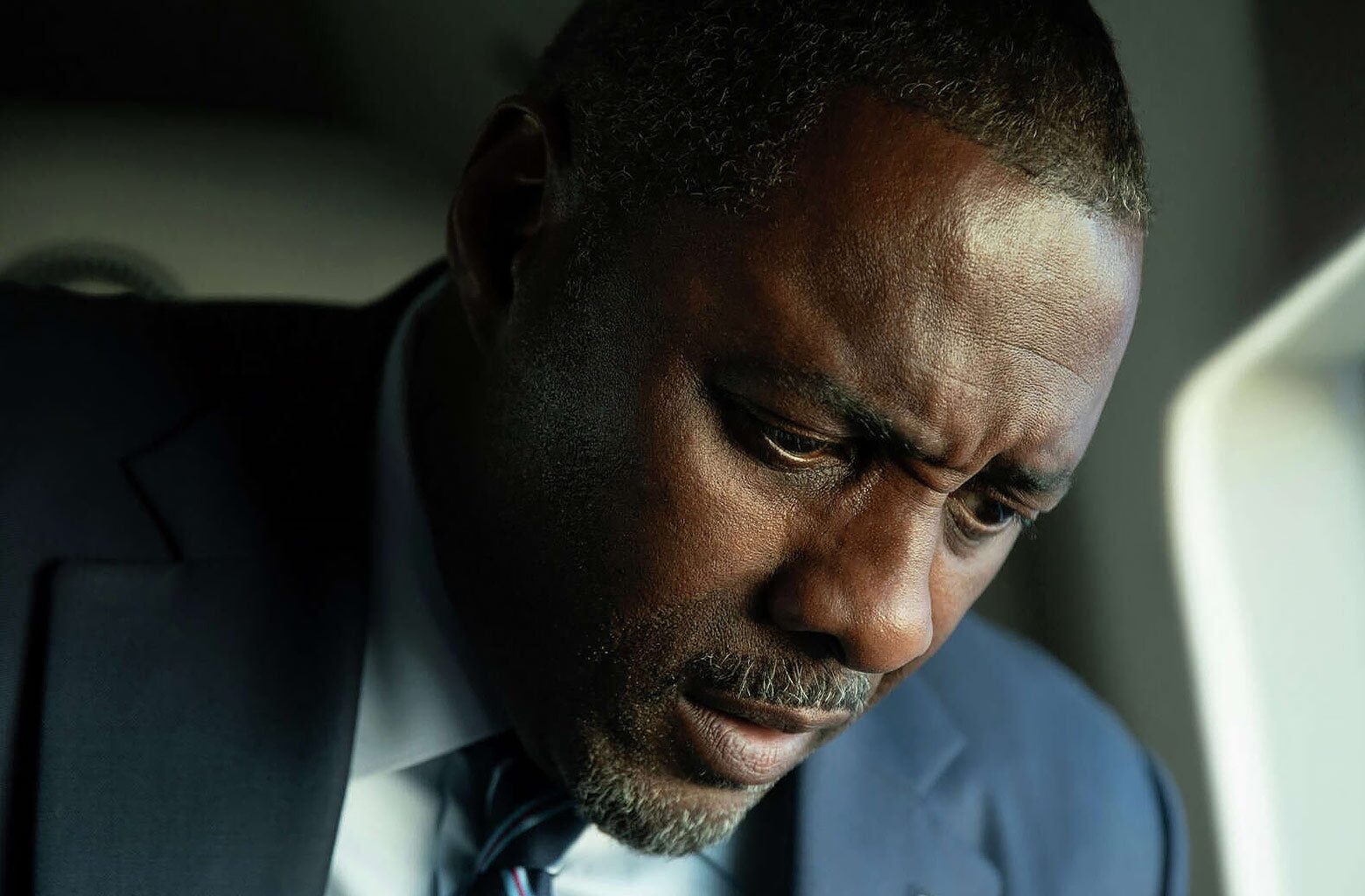

In the movie, the president is an Obama-type figure identified only as POTUS and played by Idris Elba. In the film’s preceding episodes, various officials are mulling a proper response. Already, StratCom has placed the nuclear arsenal on high alert (DEFCON 1), a move that includes ordering the bomber pilots to go airborne (seen as a prudent move, as bombers can be recalled if things calm down). The deputy national security adviser suggests that even this might be a bad idea, as it could trigger a spiral of escalation: The Russians and Chinese would suspect that the U.S. might be preparing for an all-out attack on them—and so they would put their forces on alert as well.

The StratCom commander acknowledges this, but says it would be better than doing nothing. Our enemies have been watching their radar screens; they know that our missile-defense system doesn’t work; if we let our third-largest city go up in smoke without responding at all, we’ll appear weak—and the rest of our cities will spin into chaos. Maybe North Korea has launched this attack, hoping to spawn disorder. Maybe Russia has done it, also hoping that we’ll spin into chaos and that maybe we’ll also think North Korea is the culprit and destroy that country too. (One weakness of the film is that it’s hard to imagine why any country’s leader, even North Korea’s, would fire just one nuclear missile at the United States, especially at an American city, knowing that the American president would likely fire back with full force.)

The young national security adviser suggests at least waiting until the warhead goes off—if it does go off. Sometimes, he says, they malfunction. (Indeed they do, especially if they’re North Korean.) He also tells the president that the Russian foreign minister promised not to join the attack on the U.S., adding, “I believe him.” The president replies, a bit warily, “You do?”

The general commanding StratCom disagrees, advising the president to exploit the situation by attacking all of the missile sites, bomber bases, submarine pens, and command-control stations in North Korea, Russia, and China—thus nipping escalation in the bud. He says he could live with 10 million dead in and around Chicago if it meant there would be no follow-on attacks.

Devotees of Dr. Strangelove will recognize this monologue from the scene where Gen. Buck Turgidson, the comically voluble Air Force chief played by George C. Scott, advises President Merkin Muffley, played by Peter Sellers, to do just that. “I’m not saying we wouldn’t get our hair mussed,” Turgidson shouts, “but I do say no more than 10 to 20 million killed, tops, depending on the breaks.”

No doubt Noah Oppenheim, who wrote the screenplay for A House of Dynamite, has watched that scene a few times. The difference here, though, is that Gen. Anthony Brady (the StratCom commander, played by Tracy Letts) comes off as a calm, collected character reciting an argument that’s logical within the framework of nuclear strategy.

“Within the framework of nuclear strategy” is the caveat—and the underlying topic of this movie. Sitting in his airplane, mulling over the book of laminated pages detailing the various attack options, the president moans to Gen. Brady, “This is insanity.” The general replies, “No, Mr. President, it’s reality.”

That’s the thing about nuclear war, if and when it happens: It can’t help but be both—insane and inescapably real.

So, what should the president do? He’s flipping through the book that the officer, the one following him around everywhere with the heavy briefcase, has handed him. It’s filled with pages detailing lots of scenarios. As Gen. Brady tells him, there are “Selected Attack Options,” “Limited Nuclear Options,” and “Major Attack Options”—SAOs, LNOs, and MAOs.

The real nuclear war plan—and the book to guide the president—really does contain many variations on these options. To explain (which the movie doesn’t, probably for good reason, to avoid mind-numbing exposition): SAOs are attacks on specific sectors of an enemy’s military or economy (e.g., Russian military sites or formations near the European border, or a set of drone or tank factories). LNOs are a subset of SAOs aimed at only a handful of targets, possibly just two or three nukes set off to “demonstrate intent.” MAOs are what the acronym suggests—massive attacks on a nation’s entire nuclear arsenal or military infrastructure or, if the war escalates, the nation itself.

And the options really are detailed on laminated pages. This started with President Jimmy Carter. When he was shown the attack plans that he would read if nuclear war started, he told his briefers, “I’m pretty smart, and I don’t understand a word of this.” The manual was simplified to be like menus at Denny’s restaurants; in fact, military officers called the sheets “Denny’s menus.”

In the movie, POTUS is frustrated, even a bit baffled, by these options. He says that he heard a briefing on all of this when he first took office, but he never really absorbed it. This, too, rings true to life. Carter had a moral, even religious revulsion toward nuclear weapons, but he was, and remains, the only American president who ever played himself in the National Security Council’s annual nuclear-war exercise. (Usually a Cabinet secretary plays the president, and assistant secretaries play the Cabinet secretary.) Most presidents have preferred to avoid the subject as much as possible; it’s too awful, easily dismissed as improbable, and, when viewed from the outside, the whole subject—the idea of controlling the escalation of nuclear war—too crazy. During one National Security Council meeting about revising the nuclear-war plan, Barack Obama, growing impatient with the otherworldliness of the scenarios and calculations, said, “Let’s stipulate that this is all insane.” Then he added, “But … ” and proceeded to plunge down the logical rabbit hole that kept all the options and scenarios in place. Like the exchange between POTUS and Gen. Brady in this movie: “This is insanity”—and “This is reality.”

As the film nears its climax, the general asks POTUS which option he’s chosen. And there the movie ends. The title, “A HOUSE OF DYNAMITE,” fills the black screen.

Dana Stevens

Guillermo del Toro’s Lavish New Movie Breathes Fresh Life Into One of Science Fiction’s Oldest Stories

Read More

At first, I groaned a little, seeing this as a cop-out. But the more I thought about it, the more I concluded that this was the only sensible ending. This movie lays out how a nuclear crisis might evolve, based on how things really are—the institutions, systems, strategic logic, and the types of personalities involved in the enterprise. To go beyond that, to speculate on what a president in this crisis might decide, and what might happen next, would be the stuff of a different movie—an apocalyptic horror movie based on little more than fantasy.

The title is uttered by POTUS while he’s musing on his options. He says he heard the phrase on a podcast, someone saying nuclear weapons were like “a house of dynamite”—one lit match could blow everything up, no matter who started it or why. My guess is the phrase was inspired by the late Carl Sagan, who once described the nuclear arms race as “a room awash in gasoline” with “two implacable enemies … one of them has 9,000 matches, the other 7,000 matches, each of them concerned about who’s ahead, who’s stronger.”

Sagan made the remark on a panel of experts assembled by ABC News that aired immediately following the broadcast of The Day After. That TV movie, aired at the peak of Reagan-era Cold War tensions, was watched by more than 100 million Americans and had a major impact on a public that hadn’t previously had much exposure to details about nuclear war and its consequences.

This Content is Available for Slate Plus members only

It’s Going to Be Nominated for All the Oscars. I Hated It.

One of Our Greatest Fantasy Series Comes to a Close With a Thrilling Final Chapter

The Superheroes Are Not OK

He Was the Most Acclaimed Novelist of His Generation. He Won the Nobel. He Was Worse Than Anyone Knows.

Some have speculated that the movie also had an effect on Reagan, that it moved him away from his bellicose rhetoric and more toward arms control and détente with the Russians. This probably isn’t true. Reagan did watch the movie at Camp David. He wrote in his diary afterward, “It’s very effective & left me greatly depressed.” But it did not turn him away from his arms buildup. To the contrary, it made him all the more determined “to do all we can to have a deterrent,” so that “there is never a nuclear war.” Other events, in real life, altered Reagan’s attitude and actions.

For the same reasons, I doubt that A House of Dynamite might sway Donald Trump toward advocating nuclear arms cuts. More likely, the movie might impel him to spend even more money on his “Golden Dome,” a project that he thinks will fulfill Reagan’s dream but will wind up costing, even by today’s projections, as much as $1 trillion and probably still won’t work.

In any event, A House of Dynamite is a movie of our time, worth watching, mulling, debating, and asking officials why they are doing so little about everything.

Get the best of movies, TV, books, music, and more.