This spider is female on one side and male on the other due to a phenomenon called gynandromorphism. Credit: Surin Limrudee.

This spider is female on one side and male on the other due to a phenomenon called gynandromorphism. Credit: Surin Limrudee.

By all accounts, it began as an ordinary day in Kanchanaburi, a forested region in western Thailand. A group of local naturalists were digging through the dirt, looking for the small burrows that often hide ambush predators. What they unearthed instead was more than they bargained for: a pocket-sized spider whose body was perfectly divided — one half bright orange, the other ghostly grey.

The team, led by entomologist Chawakorn Kunsete of Chulalongkorn University, quickly realized this was no ordinary arachnid. This was a new species, but that’s not the kicker. This spider was split between male and female, a condition known as bilateral gynandromorphism.

A Spider Named Inazuma

When Kunsete’s colleague Surin Limrudee posted photos of the strange half-colored spider on Facebook, Kunsete was stunned. “Upon contacting him, I discerned that the specimen was not only a gynandromorph but also morphologically distinct from any previously described species,” he told Forbes.

The team began collecting more specimens, eventually identifying both male and female individuals.

Male Damarchus inazuma. Credit: Surin Limrudee.

Male Damarchus inazuma. Credit: Surin Limrudee.

Female Damarchus inazuma. Credit: Surin Limrudee.

Female Damarchus inazuma. Credit: Surin Limrudee.

The species, now formally described in the journal Zootaxa as Damarchus inazuma, belongs to a group of burrowing mygalomorphs known as wishbone spiders. As you may have been able to tell, they’re distant relatives of tarantulas. These spiders live hidden lives underground, building silk-lined tunnels from which they leap to snatch unsuspecting prey.

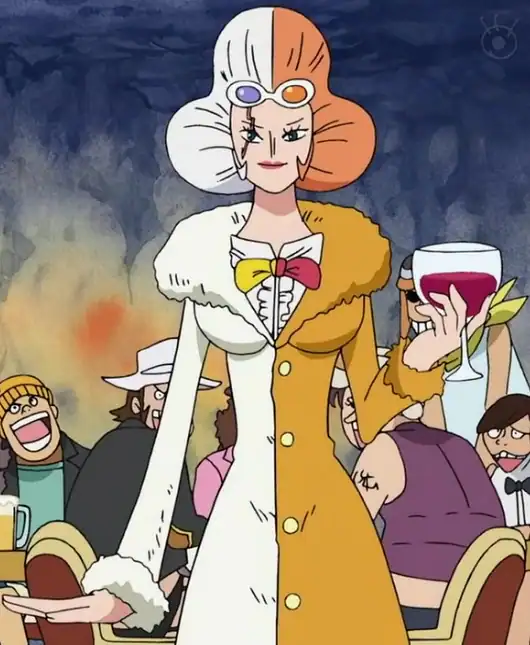

The researchers named their new discovery after Inazuma, a character from the manga One Piece, who can switch between male and female forms. As the authors explain in the study, “The Inazuma style is characterized by bilateral asymmetry, presenting distinct coloration with orange on the left side and white on the right side. This color arrangement closely mirrors the sexual dimorphism observed in this species.”

The Science of a Split Body

Example of bilateral gynandromorphism in a butterfly. Credit: Drexel University.

Example of bilateral gynandromorphism in a butterfly. Credit: Drexel University.

In most animals, sex is fixed at conception. But every now and then, nature botches the process. During early cell divisions, a chromosome can go astray, leaving one part of the developing organism genetically male and another female. The result is a gynandromorph—a creature literally half and half.

Previously, gynandromorphy has been documented in cardinals, honeycreepers, and butterflies, sometimes showing males on one side and females on the other. But in spiders, especially mygalomorphs like Damarchus, such cases are vanishingly rare. The new study notes that before this discovery, only two examples had ever been recorded in a species of tarantulas.

That makes Damarchus inazuma not just a new species, but also the first known gynandromorph in the entire spider family Bemmeridae.

Bilaterally gynandromorphic Green Honeycreeper near Manizales, Colombia. Credit: John Morillo.

Bilaterally gynandromorphic Green Honeycreeper near Manizales, Colombia. Credit: John Morillo.

The Thai specimen displays the split cleanly: the left side shows the orange coloration and larger chelicerae of the female, while the right side is smaller and ghostly white, with the male’s distinctive leg structures. Even internally, the difference runs deep, as the researchers found spermathecae, female reproductive organs, on only one side.

“The specimen possessed spermathecae, indicating the potential for reproductive capability with a male,” Kunsete explained. “However, the male reproductive organ was absent at the time of collection.” In other words, this spider could never reproduce naturally.

Fierce Little Burrowers

The spiders were found near Nong Rong, in a disturbed forest patch bordering farmland and a roadway. The collectors — Limrudee, Patiphan Chamnanpa, and Sarunphat Amuntaikul — literally dug them out by hand, uncovering silk-lined burrows that looked like miniature wishbones.

Female D. inazuma measure about an inch long and glow with a rich orange hue, while males are smaller, pale grey, and covered in what the researchers describe as “a white layer (unknown material)”. Kunsete suspects that this coating might serve as camouflage or protection, but it remains a mystery.

When disturbed, these spiders can be surprisingly fierce. “During fieldwork, we frequently observed this spider exhibiting aggressive displays, including the baring of fangs and occasionally the production of droplets at the fang tips,” Kunsete continued in an interview with Forbes. “Based on these observations, I infer that the species is probably venomous (to small insects?).”

Despite their menacing looks, there’s no evidence that D. inazuma poses a threat to humans. Like most mygalomorphs, it’s more likely to retreat than attack.

Straight Out of an Anime

Inazuma from the One Piece anime. Credit: One Piece Wiki.

Inazuma from the One Piece anime. Credit: One Piece Wiki.

The researchers point out that gynandromorphy occurs in perhaps one out of 17,000 spiders in some species, though that estimate mostly applies to true spiders rather than burrowers. In mygalomorphs, it’s even rarer. Before Inazuma, no one had ever seen such a case in this lineage.

The cause, according to the Zootaxa paper, could involve the loss of sex chromosomes during early development, possibly triggered by parasites or environmental stressors. The authors cite work suggesting that nematode infections might sometimes interfere with sex determination in arachnids.

This spider, then, is both anomaly and clue, hinting at the deep, often chaotic mechanisms that shape life’s diversity. As Kunsete puts it, “What surprised me most was that this was not only the first record of a gynandromorph in the Bemmeridae family, but also a new species from Thailand. I feel truly grateful and fulfilled, especially because this discovery was only possible thanks to the support and collaboration of many people.”

For evolutionary biologists, D. inazuma offers a rare chance to peek behind the curtain of sexual differentiation. Understanding how a single genome can split its developmental path in two could reveal new insights into the evolution of sex itself.

And for those of us who just marvel at the living world, it’s a reminder that nature is far more fluid than the categories we impose on it.