The Webb telescope captures Io, one of Jupiter’s moons, where tidal heating is so intense that it fuels volcanoes that release lava and sulfur.

It is a world in eternal torment, where the ground writhes, the mountains tremble and rivers of lava pour incessantly across the surface. Io, one of Jupiter’s moons, is the most volcanically active place in the entire Solar System.

Now, thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), scientists have been able to peer into this distant hell with new eyes, discovering never-before-seen details about its volcanoes and atmosphere.

Titanic forces. Jupiter’s powerful gravitational pull, combined with that of the other Jovian moons, subjects it to a continuous game of stretching and compression. It’s as if the moon is constantly being squeezed by invisible hands.

This process, called tidal heating, generates internal heat so intense that it melts rocks and minerals, fueling myriad active volcanoes that spew sulfur and hot lava.

The James Webb reveals a colossal eruption. In November 2022, the JWST turned its sensitive infrared eyes towards Io for the first time. The images collected by the near-infrared spectrograph, capable of measuring the temperature and chemical composition of the surface with great precision, revealed a volcanic eruption of extraordinary energy in the Kanehekili Fluctus area.

Continuous cycle. Additionally, for the first time, scientists have observed that some volcanoes on Io emit an excited form of sulfur monoxide, a chemical signature that confirms a hypothesis formulated by Imke de Pater and her team over two decades ago. The telescope also detected a spike in thermal emissions coming from Loki Patera, a giant, deep and unstable lava lake. Here, a thick solid crust periodically forms on the surface, only to sink back into the molten lava below, renewing the landscape in a constant cycle of destruction and rebirth.

Nine months later. In August 2023, the research team – whose results were published in JGR Planets – had a second opportunity: to observe Io again, in the same regions, as the moon passed through Jupiter’s shadow. This condition is precious for astronomers, because it allows them to capture weak infrared emissions normally submerged by sunlight.

The new images told a story of transformations: the lava flows of Kanehekili Fluctus had extended up to 4,300 square kilometers, quadrupling the area compared to 2022. At Loki Patera, however, a new cooled crust had formed, in perfect coherence with the cyclic behavior observed over the decades.

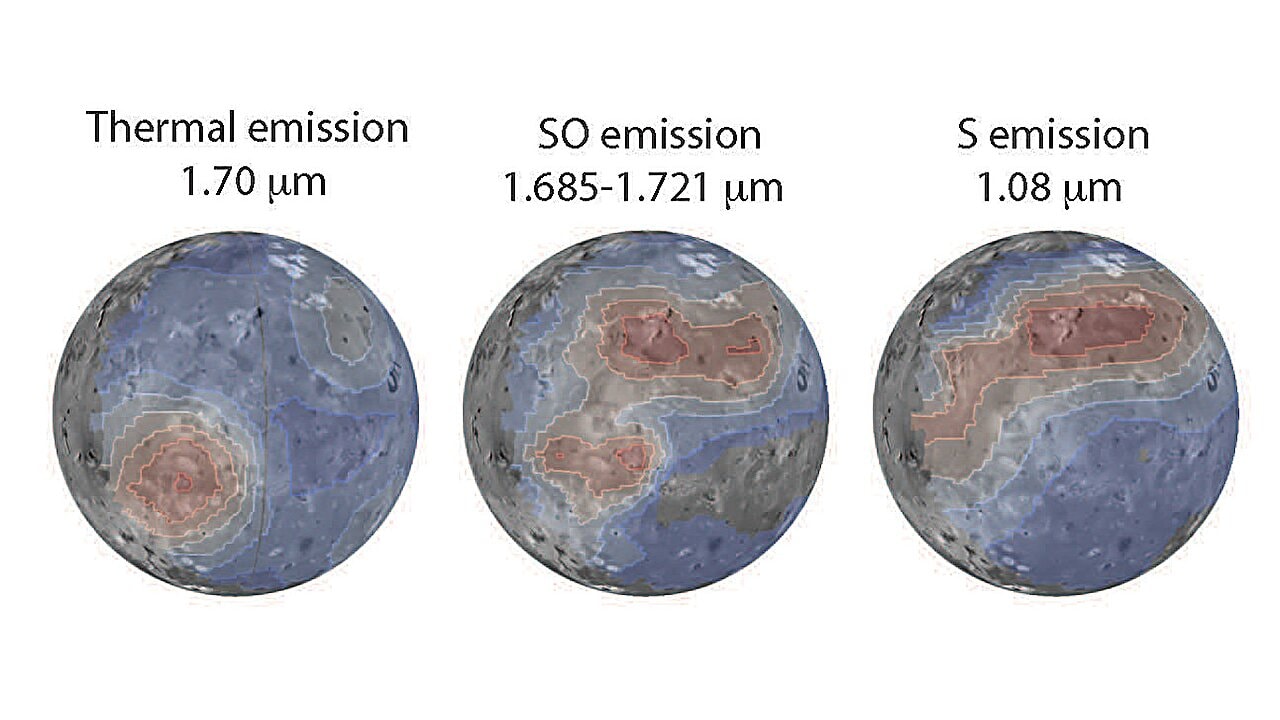

The mystery of “invisible volcanoism”. But the JWST also captured something unexpected: sulfur monoxide emissions coming not only from Kanehekili, but also from two regions without visible volcanoes.

Scientists have attributed them to a phenomenon they have dubbed “invisible volcanism” — underground or widespread processes that still elude direct observation tools.

And for the first time, images from 2023 revealed emission of sulfur (S₂) gas at previously unseen wavelengths in Io’s atmosphere (specifically the excited state centered around ~1707 nm and the atomic emission of neutral sulfur at wavelengths around 1082 nm and 1131 nm). Unlike sulfur monoxide, which concentrates in patchy areas, sulfur gas appeared more evenly distributed over a large portion of the Northern Hemisphere.

A game of electrons and sulfur. The new observations have led to another fascinating revelation: these sulfur emissions do not come directly from volcanoes, but are the result of an electrical process. Electrons from Io’s plasma “torus” (the plasma torus is a giant donut of charged particles surrounding the moon’s orbit) penetrate its sulfur dioxide (SO₂)-rich atmosphere, exciting sulfur atoms and causing them to glow in the infrared. The orientation of the JWST and the position of the Northern Hemisphere relative to the torus explain why these emissions are concentrated precisely in that area.

A stable balance. When the James Webb data are compared with those collected over the years by the Keck and Hubble telescopes, a coherent and unexpected picture emerges: despite the volcanic fury that constantly devastates the surface, the system formed by Io’s atmosphere and the Jovian plasma torus seems stable for decades.