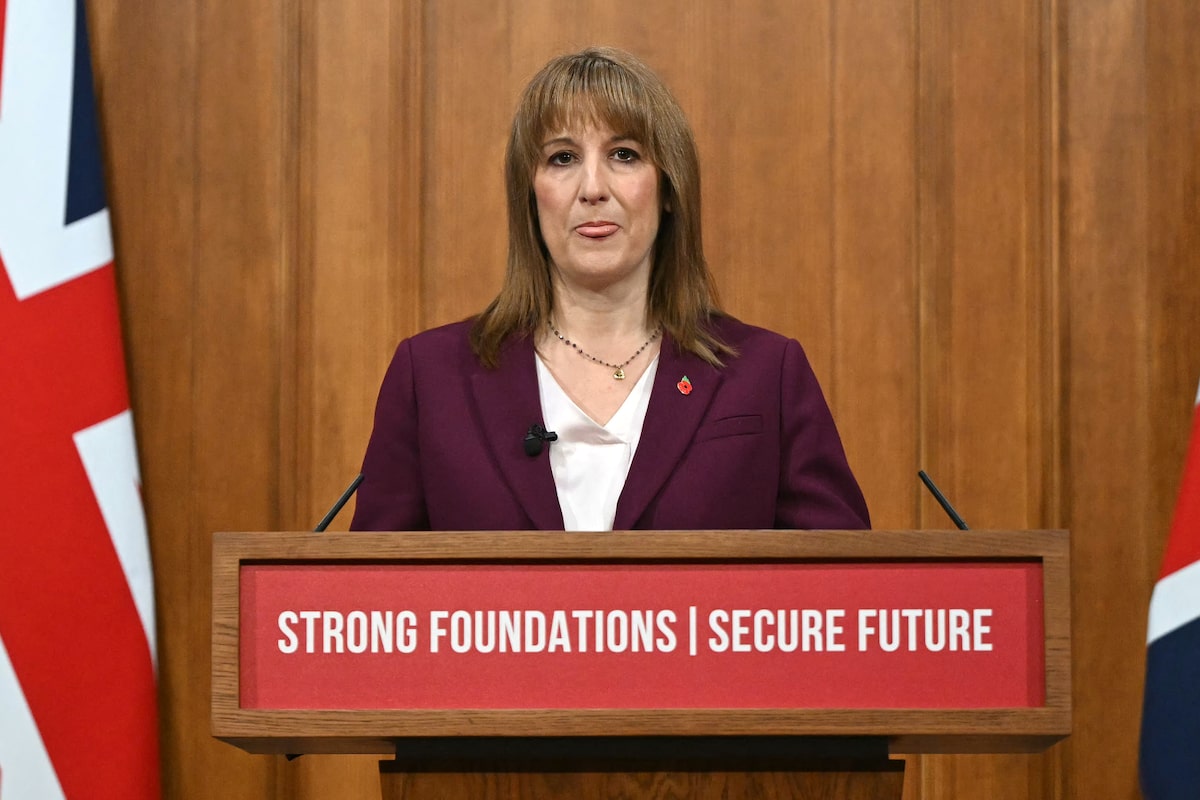

Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves delivers a speech at 9 Downing Street in London on Tuesday.JUSTIN TALLIS/AFP/Getty Images

Just hours before Finance Minister François-Philippe Champagne tabled the federal budget in Ottawa on Tuesday, his British counterpart was scrambling to calm investor nerves with a speech delivered in advance of the budget she plans to table later this month.

In an unusual move, Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves delivered an address she described as a “scene-setter,” to prepare markets for major tax increases in her Nov. 26 budget, as her Labour government struggles to stabilize the country’s runaway debt and deficit.

“If we are to build the future of Britain together, we will all have to contribute to that effort,” she said. “I do not believe that our past has to determine our future or that a stuttering economy, poor productivity and falling living standards is somehow Britain’s destiny.”

The sombre tone of Ms. Reeves’s speech was a reflection of the fiscal vise in which her government finds itself. Britain’s deficit is expected to hit 4.3 per cent of gross domestic product this year, while its net-debt-to-GDP ratio approaches 95 per cent.

Carney’s budget is a Trump survival plan. Here are the highlights

In her first budget, after Labour’s majority win in the mid-2024 general election, Ms. Reeves increased taxes by £40-billion ($73.5-billion) in what the Financial Times described as “the biggest tax-raising fiscal event in a generation.” The Chancellor promised then not to repeat the exercise. But her speech on Tuesday suggested she will break that vow on Nov. 26.

Meanwhile, across the English Channel, the government of French Prime Minister Sébastien Lecornu continues to teeter as it attempts to pass a budget before year-end that tames the country’s spiralling deficit. The prospects of that happening look increasingly doubtful as both far-left and far-right députés in the National Assembly resist spending cuts.

At 5.4 per cent of GDP, France’s 2025 budget deficit is already almost twice the upper limit allowed under eurozone budget rules. The country’s net debt stands at 108 per cent of GDP.

Mr. Lecornu had proposed measures to reduce the deficit to 4.7 per cent of GDP in 2026, a modest decrease, but a sign of progress. Without a majority in parliament, however, his government is locked in negotiations with opposition parties seeking to extract concessions in exchange for their support.

Mr. Lecornu agreed to suspend President Emmanuel Macron’s hard-won pension reforms, which included raising the retirement age to 64, until at least after the 2027 presidential election in order to survive a non-confidence vote last month. But that only created an even bigger hole in the budget.

Compared to France and Britain, Canada’s fiscal situation looks practically rosy. Despite big increases in defence and capital spending laid out in Tuesday’s budget, the federal deficit is projected to rise to 2.5 per cent of GDP in the current fiscal year and decline to 1.5 per cent by 2030. The net-debt-to-GDP ratio is set to increase slightly to about 43 per cent by then.

Opinion: Budget shows Carney doesn’t know how tough it is out there on Main Street

Opinion: A ‘generational budget’ that does little but set federal spending adrift

Of course, the federal budget only tells half the country’s fiscal story. When provincial-government debt is added in, Canada’s overall net-debt-to-GDP ratio hovers at around 75 per cent. Because net debt includes the assets of the Canada and Quebec pension plans – assets that are not technically available to governments to repay their own debts – some economists prefer to look at the levels of gross public-sector debt levels. Using those metrics, Canada’s debt situation looks somewhat more concerning.

Still, we’re not France or Britain – not yet anyway.

Years of kicking the can down the road have left them with no palatable budget choices. Cuts to welfare benefits, health care and pensions are inevitable. And that has created volatile political conditions in both countries, where far-right parties are leading the polls and on the cusp of electoral breakthroughs.

To avoid that fate, Canada will need to confront its own budgetary time bombs in an orderly manner. Rather than boasting about Canada’s fiscal capacity, the budgetary chaos that France and Britain are experiencing should serve as a warning for Prime Minister Mark Carney’s government that minor adjustments to program spending will only come back to haunt us in the long run.

Mr. Champagne’s budget projects about $60-billion in spending cuts over five years, but leaves the big-ticket items of Old Age Security and provincial transfers untouched. Spending on elderly benefits is set to increase by 25 per cent to $104-billion by 2029-2030; equalization payments are projected to rise by 16 per cent to $30-billion. Compare those figures to the budget’s projection for an overall program-spending increase of just 7.5 per cent by 2030 – a target that will be difficult to meet without reforming OAS and transfer payments.

In many ways, Canada has inherited the best of France and Britain. But if we act soon, we can still avoid inheriting the worst of them.