Not long after graduating from the University of Texas at Austin in 2021, Donald King landed a job as an associate at the London-based consulting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers. King had always assumed he’d work in business — he’d started his own hedge fund while still an undergrad — but a few years into the job, he decided he was more interested in tech than finance. Early in 2024, after PwC announced a $1 billion investment in artificial intelligence, he switched roles and started working as a data scientist for the company’s nascent Global AI Factory.

King worked with engineers at PwC and OpenAI to customize teams of autonomous AI systems, called agents, for Fortune 500 companies. Normally, multinational companies contract thousands of people to modernize their backend software. Home Depot, for example, might enlist an army of consultants to update inventory or its SAP accounts-payable processes. Recently, though, AI agents have gotten pretty good at that kind of work. Consultants are some of the most prolific AI users, and King thought of himself as a kind of pioneer in a New Age of automation, creating and then deploying agents for PwC’s clients. “P-dubs,” as King calls it, expected a lot from its workers. King put in 80-hour weeks, which kept the 26-year-old from going out on weekends. But he made six figures and lived in a one-bedroom high above Hudson Yards in a building with a pretty nice gym, where he sometimes took camera-off meetings while doing pull-ups. “I was a meat slave,” he says, “and it was kind of a dream job.”

The goal was to help clients “do more with less,” as King’s bosses reminded him, by automating whatever task they threw at his team. Occasionally, when King lingered on the downstream effects of his work, he felt like Dr. Frankenstein looking at his monster. “There was a sense of awe and then it’s kind of shock and fear and almost a disgust,” he says. King knew consultants were called hatchet men for a reason, but it was becoming clear to him that the agents his teams built were capable of wiping out not just individual jobs but entire job categories. “There was a large telecommunications client, and we were doing some crazy stuff for them. Once, we created an agent that was literally, like, a Microsoft Teams agent that was pretending to be a real, human employee,” King says. “That’s when me and my other teammates were like, ‘Whoa, we need to sit and just talk for a little bit. What are we even doing right now?’ Because that’s someone’s job, and if we have 45 of these agents working together, how many human jobs is that going to take? Are we just automating away people’s livelihoods?”

One night, after preparing for a big presentation, King stayed up late into the night talking with a few of his co-workers about the implications of their work. One colleague, a senior manager, wondered whether his kids should even bother studying computer science. “We just kept asking things like, ‘What exactly are we doing with this job?’ ‘Am I going to be protected from what I’m building?’ ‘Should I be upskilling and trying to learn new things as well?’”

When the big four consulting firms started laying off employees last year, King wasn’t concerned. It’s not uncommon lately for young consultants to spend weeks at a time “on the bench,” waiting to be drafted by a project manager, but three years into the job, King’s utilization — his time assigned to projects — was 100 percent. He felt even more secure when, late last year, he entered a companywide AI hackathon and, out of thousands of entries, won first place. In October, he presented his winning product, a team of AI agents he’d built in his free time, to some 70,000 PwC employees. “I was thinking, Oh, this is going to unlock so many opportunities for me. I literally thought to myself, I’m safe from the layoff.” Then, two hours after King finished his presentation, PwC laid him off.

King recorded a video of his own firing. In it, a partner with a southern drawl matter-of-factly explained that PwC was reshuffling “to align our workforce to accelerate our business strategy.” King came to see AI — and his work in particular — as an ouroboros. The AI agents he built were intended to reduce by 30 percent both the client’s team and the team of PwC consultants working for that client. “It was actually like I was just feeding myself into the AI meat grinder.”

In the months following his layoff, King started his own marketing agency and became a kind of layoff influencer, telling his story on TikTok and offering advice. He’s got a captive audience — in July, “new entrants” as a percentage of the total unemployed population hit its highest number since 1988. Over the past year, King has watched former clients go through their own cuts, often affecting entry-level jobs. He won’t share their names, but plenty of Fortune 500 companies like Intel, Salesforce, Chevron, UPS, Microsoft, and Procter & Gamble have enacted or announced major layoffs this year.

The extent to which recent layoffs are the result of automation is contested, but plenty of executives have nakedly blamed AI. Klarna CEO Sebastian Siemiatkowski says AI helped him shrink his workforce by 40 percent. Marc Benioff suggested AI agents were responsible for 4,000 job cuts at Salesforce, and AI was an explicit part of Accenture’s 11,000-person reduction. Lufthansa announced plans to eliminate 4,000 jobs in the coming years thanks to AI, and Goldman Sachs is piloting Devin, an AI agent that will automate software engineering, which doesn’t bode well for the 12,000 human engineers currently doing that work.

In August, economists at Stanford’s Digital Economy Lab found that AI is having a “significant and disproportionate impact on entry-level workers in the American labor market.” In particular, it’s currently affecting workers between the ages of 22 and 25 with jobs in AI-exposed fields like coding. That’s because AI has allowed for “prompt engineering” and “vibecoding,” the practice of building software using plain English; it can also generate much of the code that junior developers once wrote. The Stanford paper found a nearly 20 percent decline in employment for young software developers — perhaps making entry-level coders the first statistically significant casualties of AI automation.

There is a sense of anticipation among everyone — employers, job hunters, economists, academics — about what kinds of work will go the way of coding. When Microsoft Copilot recently launched agents capable of carrying out complex requests in Excel, Word, and PowerPoint, it called their new features “vibe working.” Over the past few months, I’ve heard the terms vibe advertising, vibe writing, vibe designing, and vibe physics. Talk of an economy dominated by AI output is making it difficult for Gen Z to plan for the future. “I’ve been having that dreaded conversation about law school with my parents,” says Meghan Keefe, who spent the past seven months searching for an entry-level job in media. “I just registered for the LSAT to appease them, but I’d enter the workforce four years from now and AI is going to be more advanced. It seems to be taking paralegal jobs away from people who have already been working there and people who have gone to law school, so that’s scary. That decades-old fail-safe is seemingly gone.”

It’s hard to fault her and other zoomers for their nihilism. Executives at Ford, JPMorgan Chase, and Walmart have publicly warned of major disruption to the labor market. Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei says AI tools — the very thing his company is building — could soon eliminate half of all entry-level white-collar jobs. IMF chief Kristalina Georgieva says a “tsunami” is coming for labor markets that could affect 60 percent of jobs in advanced economies. And Elon Musk predicts AI and robots will replace all jobs. “It does not matter if you are a programmer, designer, product manager, data scientist, lawyer, customer-support rep, salesperson, or a finance person — AI is coming for you,” Micha Kaufman, the CEO of Fiverr, a freelance marketplace, said shortly before laying off 30 percent of his staff.

The speed with which AI has measurably displaced entry-level coders concerns Anton Korinek, head of the Economics of Transformative AI Initiative at the University of Virginia. “Over the next five months, I would definitely expect it to bleed into additional white-collar areas. Even if companies aren’t going through huge layoffs, maybe they’re now running pilots with AI agents; maybe they are saying, ‘Hmm, let’s not commit to hiring that associate,’” he says. Korinek has been studying AI’s potential impact on the economy for more than ten years, and while he’s always believed it would roil the labor market, he never thought that moment would arrive so soon. “You can really feel this coming. We’re at the point where it’s important for people who are honestly concerned about rapid advances that would lead to rapid job-market destruction to raise alarm bells,” he says. “Gen Z is first where all of us are going to have to go.”

Anna graduated from a small liberal-arts school in 2023. A few months later, she accepted an offer to work as a copywriter at an ad agency specializing in digital-media ads for beauty brands. A history major in college, Anna, who asked to be identified by a pseudonym, hoped to be a writer, and she saw advertising as a good way to make money in the meantime. For the first six months of the job, AI was hardly ever mentioned. Then her bosses began encouraging her to “experiment” with ChatGPT. Last spring, AI became a requirement of the job. Now, Anna and her co-workers have AI programs read voice-overs, which was once part of their job, and use LLMs to generate ideas. “There are these awful AI-generated images that are just scary mannequin people and have really dumb taglines. You’re working on a night skin-care mask or something, and ChatGPT is going to say, ‘Get your beauty sleep!’ Just the dumbest stuff,” she says. “And the worst part is that the marketing teams at these companies love it. They’re like, ‘This is amazing!’” Anna would much rather not use AI, but she has no choice. “My boss told me, ‘You should be talking loudly in the office about using AI’ and ‘Don’t bash AI in front of the higher-ups because that will make you look bad,’” she says. “It’s so obvious I’m training something to replace me, and I think that’s kind of why I’ve been hesitant. Because if I can make it do my job successfully, they don’t need me to do my job anymore.”

Gen-Zers are now accustomed to the fact that AI permeates white-collar work starting with both sides of the hiring process. People looking for jobs use AI to tailor résumés and cover letters in order to get the attention of AI programs vetting applications. Managers at Shopify must now justify hiring a human by first explaining why AI can’t do the job. “In interviews, it has been, ‘What’s the measurable impact of what you can do versus what a machine can do?’” says a 27-year-old consultant who’s been job hunting since Deloitte laid him off in September. “I feel like what I went to school for is now just being automatically populated by an AI within a matter of seconds.”

In the office, bosses like Anna’s push AI as if its use is a patriotic duty, like tending to a 21st-century Victory garden. And each use case, no matter how well-intentioned or innovative, can feel like a step toward job annihilation. “I automated my co-worker’s job with AI right before rumors of incoming layoffs, and now I am not sure how I feel,” posted Asm Goni, a 22-year-old employee at a nonprofit in Queens, on LinkedIn in October. Goni, who graduated from St. John’s University with a computer-science degree in 2024, had heard that his co-worker was combing through a database that included some 4,000 client IDs — tedious work that would have taken a week or more to finish. Using open-source AI tools and vibecoding, Goni created a tool that automated the entire process. “The instructions to AI were literally like, ‘Step one: Do this. Step two: Once you’re here, go there. Step three: Once you’re there and you’ve copied this information, put it back into the spreadsheet.’” Ultimately, Goni’s co-worker wasn’t laid off, but the experience made him anxious. “If everyone understood how to use AI — how to prompt it and order thoughts and provide references — a lot of jobs would be eliminated tomorrow,” he told me. “The reason you haven’t seen mass layoffs is ignorance.”

Ignorance isn’t really what’s holding the line — executives at the world’s largest employers are certainly aware of AI’s capabilities and its limitations. But layoffs aren’t the only measure of AI’s effect on the labor market, especially when it comes to creative industries that run on freelance work. Several graphic designers told me that business was slow this year and they suspected AI had something to do with it. An illustrator said she was happy to hear from a prominent Substack writer about a potential commission, but when the writer heard the cost of original artwork, they went with AI art instead. The director of the Museum of the City of New York, Stephanie Hill Wilchfort, admitted she no longer needs to hire copy editors to work on annual reports. It hasn’t saved the museum much money, but for an arts nonprofit, every penny counts.

Joshua Neckes co-founded Bobsled, a data-sharing platform, in 2021 and quickly grew it to around 50 employees. Over the past year, he’s stopped hiring junior coders. AI has also slashed his legal overhead. “I just throw a contract into ChatGPT and say, ‘Call out the passages that are unusual.’ Then I read it and I’m smart enough to understand what’s going on here. Then I bring it to my lawyer with my notes all ready. An associate doesn’t need to look at the thing, and I just cut five hours off my legal bill.”

Neckes sees AI as a total workforce reset. “Our economy has a decent percentage of fake jobs that barely had a reason to exist in the first place. There’s just no reason to deal with the headache of having young employees who frequently do the wrong thing, who frequently, you know, take up time and space.” I asked him what Gen Z — the entry-level coders and associate attorneys in those fake jobs — were supposed to do without opportunities. “Be smarter around the new shit and be cheaper,” he says.

This attitude is, unsurprisingly, popular among CEOs. At a Beverly Hills conference last spring, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang said that “you’re not going to lose your job to an AI, but you’re going to lose your job to someone who uses AI.” Universities, HR types, and clickbait career sites are onboard, too, urging students and workers to futureproof their careers by “reskilling” and beefing up their soft skills. Ravin Jesuthasan, a self-described “future-of-work futurist,” told me, “The quantum of upskilling and reskilling that each of us will need to do is going to increase exponentially.” AI fluency will be central to what Bryan Ackermann, lead AI strategist for the global headhunter Korn Ferry, calls “a new set of job families.” What kinds of jobs are these, exactly? “Prompt engineering, but I’m not sure how long that is going to be a thing,” he admits. “I’ve heard ‘AI ethicist,’ ‘AI bias tester,’ or I’ve heard ‘AI monitor.’” The day-to-day work of these roles is TBD — but so is the day-to-day work of most white-collar jobs in five years. “There’s going to be a rapid evolution of what it means to be a manager,” Ackerman continues. “For example, how do you have a difficult conversation with an employee when the employee that’s the subject of the difficult conversation is not human?”

“Junior-level people are going to have to have a little bit more ambition,” says Elisa Silverglade, director of automation for Techromatic, a small information-technology consultancy in Westchester that works with small and medium-size law firms. Before Techromatic, Silverglade spent 15 years running her ex-husband’s law office, so she understands the interminable busywork that firms run on. “The copying and pasting, the uploading and downloading, the renaming, the saving, the attaching, the filing and the filling. Humans don’t need to do that part anymore,” she tells me. Silverglade doesn’t want paralegals and associates to see technology as a threat to their jobs — her LinkedIn describes her ethos as “automating with empathy.” “This is not replacing a person. This is allowing people to have time to do higher-value activities that not only serve the company better but are more fulfilling,” she says. But how many ambitious employees do we expect employers to retain? And if AI is only getting better, what’s the point of upskilling?

When Bryce Harris was in the eighth grade, he built his mom a computer using only YouTube and parts he bought at a local computer store. In 2024, he was among the first students at the University of Texas at Austin to graduate with a degree in informatics, the study of computational systems. Harris went straight to work for Microsoft, where he was an AI product manager, building and implementing AI agents for small businesses. Last spring, less than a year into the job, Microsoft laid off Harris, one of roughly 15,000 employees the company has axed this year. Harris didn’t blame AI for the layoff, but I asked him whether, as a Gen-Zer with frontline experience of AI’s integration into the labor market, he had ever experienced automation anxiety. “I’m an optimistic person,” he told me. “I try to stay away from that anxiety stuff. And as a builder, as an automator, I built the agents and I built those systems that can help, you know, redistribute those jobs.” Part of Harris’s job, he explained, was to provide companies with a plan to reabsorb employees whose jobs had been automated. I asked Harris whether the companies have adopted those plans. “I wouldn’t say I’ve seen it, but I’ve created programs that would have helped do that. Did the companies listen to what I advised? Well, that’s another thing.”

If the number of entry-level jobs dwindles across industries, naturally, the supply of experienced employees will wane. Without entry-level positions, how will the next generation of middle managers and executives get training? Millennials would be the last keepers of unwritten workplace knowledge, the intangible lessons and institutional know-how that haven’t been, or can’t be, fed into LLMs. What would the economy look like then? For those hoping to prevent the worst-case scenario, automation concerns have inspired a new wave of interest in ideas like universal basic income, profit sharing, and employee-owned enterprises (see Bernie Sanders’s recent video, “AI Could Wipe Out the Working Class”). But policy moves a bit slower than AI and, if income is abruptly severed from labor, there is a genuine fear that the chasm of inequality may quickly solidify. That fear has launched a meme warning that the deadline for prosperity is fast approaching. As @creatine_cycle recently posted on X, “You have 2 years to create a podcast in order to escape the permanent underclass.”

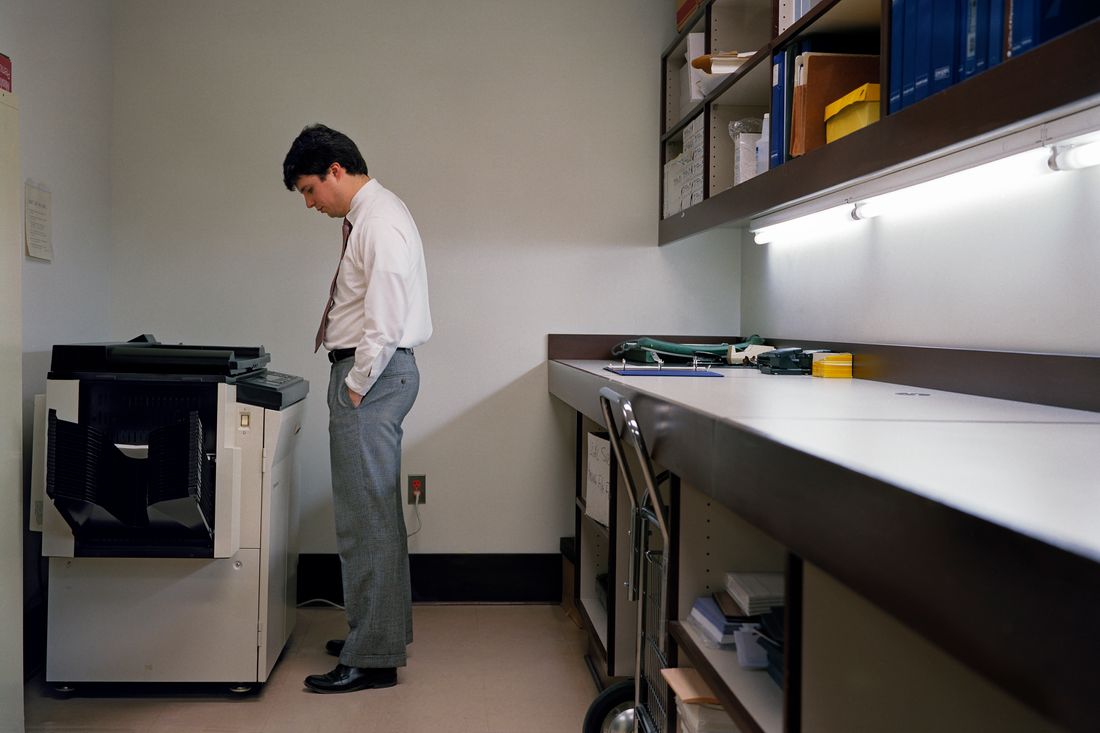

You, a white-collar worker with a decade of experience, probably have a hard time imagining AI automating your job. And it’s true that, at this very moment, AI probably can’t navigate your company’s ancient, proprietary software; it doesn’t have the relationships with clients that you’ve developed over the years; it can’t pick up a report from a printer tray and walk it down the hall to your computer-illiterate boss; and it certainly can’t walk the fine line between team-building gossip and lawsuit-waiting-to-happen at happy hour. It’s probably comforting to imagine that automation really poses a threat only to young people who haven’t yet developed your skills, who know only what they learned in a classroom. But what happens when AI becomes proficient at the core functions of your job? When management begins to realize your company can, as they say at P-dubs, do more with less? In September, OpenAI released the results of a study that tested AI’s ability to accomplish 1,320 “real-world economically valuable tasks” across 44 occupations. The assignments were created by people with experience at Aetna, Bank of America, BBC News, Douglas Elliman, HBO, Boeing, the Justice Department, and others. To judge ChatGPT’s performance, researchers had professionals with plenty of real-world experience complete the tasks so that the results could be compared blindly. A real-estate agent designed a sales brochure for a Florida home; a registered nurse assessed skin-lesion images and drafted a consultation report; lawyers were asked to draft wills or memos on complex mergers.

On average, the humans won — but barely. AI’s biggest stumbling blocks weren’t hallucinations or factual errors but issues like formatting and following instructions, areas where AI is fast improving. “AIs have quietly crossed a threshold,” wrote Wharton professor Ethan Mollick on Substack. “They can now perform real, economically relevant work.” There is no guarantee AI will improve from here, and many economists believe that, like past technologies, AI will ultimately create more jobs than it kills. But Korinek, the Virginia economist, believes advances in agentic AI over the coming months will rapidly expand what these systems can handle autonomously, from research and analysis to creative problem-solving. “Within three years, I expect AI systems will write much better economics papers than I could,” he tells me. When I suggest that in the future, we’ll all work as plumbers, carpenters, and artisans, Korinek cuts me off. “Have you seen the robots lately?”

He’s referring to videos made by Unitree, the Chinese company that has surpassed Boston Dynamics as the premier producer of dystopian robot hype videos. Korinek mentions Unitree because the company is already producing and selling robots relatively cheaply (they’re available on Amazon), an indication that widespread adoption may be close. In fact, interest in embodied AI (nerdspeak for robotics) has skyrocketed in recent years, and plenty of companies are vying with Boston Dynamics and Unitree to produce droids to work in factories, deliver goods, fight wars, pick apples, wash windows, put out fires, and carry out many other jobs. 1X recently launched sales for NEO, a $20,000 humanoid, marketing the bot as a housekeeper. Houston-based Persona AI is focused on humanoids that will do 4-D — dull, dirty, dangerous, and declining — jobs. The use-cases tab on its website show an array of humanoid renderings arranged like Playmobil on a child’s shelf. A miner holds a jackhammer, a builder holds a nail gun, a welder holds a blowtorch, and a fabricator holds an angle grinder.

Even if humanoids prove to be lousy at the skilled trades, robots are already replacing low-skill jobs. Over the summer, Amazon announced the deployment of its millionth warehouse bot. In the press release, the company touted the number of employees who “have been upskilled.” At the same time, it has cut nearly 30,000 jobs since 2022 and has plans to cut as many as 30,000 more in the near future. And the company isn’t going to stop there. Executives told the board of directors that they hope automation will allow Amazon to sell twice as many products by 2033 without adding to its workforce — the equivalent of about 600,000 jobs. Executives are well aware of the optics. Internal documents obtained by the New York Times discuss avoiding terms like “AI” and “automation” in favor of euphemisms like “advanced technology.” Robots, they suggest, should be called “cobots.”

For every zoomer suffering automation anxiety, there seems to be another taking job-search struggles or layoffs in stride, embracing a Gen-Z ethos popularized in meme taglines like “career minimalism” and “I don’t dream of labor.” Some offer rationalizations that border on the spiritual. They look forward to careers as fashion entrepreneurs, influencers, and union organizers. Few blame AI for their woes. Some offer an outlook that complements Huang’s philosophy: AI doesn’t lay people off; people lay people off. Last spring, Noah Farber, 25, was laid off from his job as an engineer for a large Brazilian company that makes mobile video games. The job paid well, but he felt dissatisfied working crazy hours just to build “another iPhone game the world doesn’t need,” as he puts it. “Getting laid off was really nice actually. I realized that I don’t want a career because a career is an identity. I just want a job to get paid so I can eat,” Farber says. Now, he’s working as a dishwasher at a Whole Foods outside Dallas.

At some point in my conversation with Farber, I mention Amazon’s fleet of robots and suggest Jeff Bezos could, conceivably, automate other jobs in his kingdom, like Whole Foods dishwashers. He’d just pivot again, he says. “I like dishwashing. It’s tough on my body, but I’m working through that and now I finally have time for music and art.”