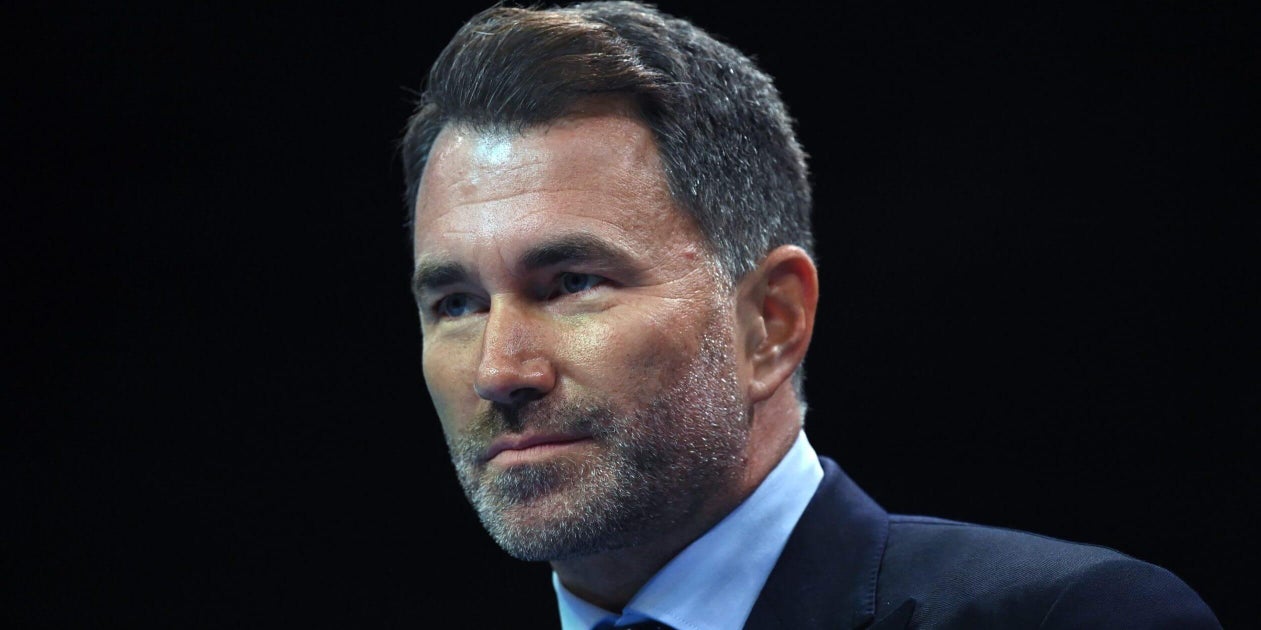

It’s fight week for Matchroom Boxing and, for the company’s chairman, Eddie Hearn, that means another week in front of multiple microphones and cameras.

During an average fight week, Hearn estimates he does around 20 to 30 interviews as a promoter. But this is not an average week. This is the week of Chris Eubank Jr versus Conor Benn II, two of the sport’s biggest British names, at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium on Saturday night.

It means Hearn can expect to be considerably busier with his publicity commitments — not that he minds. Boxing, he says, is best described as a “hyperbole of noise”, and the 46-year-old considers contributing to that as being all part of the job.

It has been 15 years since he promoted his first fight (Audley Harrison’s lacklustre defeat to David Haye), and in that time, both everything and nothing have changed for Hearn, whose father Barry founded Matchroom in 1982.

In 2010, as 31-year-old Hearn walked a dejected Harrison back to his changing room, he heard a voice call out from the crowd: “Oi, Hearn, you’re a s*** promoter.” He has proved that sceptic wrong, building Matchroom’s boxing offering into a global enterprise that will have put on 43 fights in 10 countries this year. But that doesn’t stop the criticism — sometimes abuse — coming his way, with Hearn believing that boxing’s social media community is “the most toxic” he’s ever seen.

“I think I’ve got very thick skin,” he says, “but if you’re passionate about something, love what you do and are constantly criticised, it does get to you. Imagine posting something like: ‘Great show this Saturday, who you got winning?’. And 10 minutes later, you read the replies and it’s like: ‘You’re a p****, you’re scum’. You laugh, but after a while, it does infiltrate you.”

While some aspects of his role have remained the same since that opening salvo in 2010, others have changed beyond all recognition.

The impact of Turki Al-Sheikh, the chairman of Saudi Arabia’s General Entertainment Authority, and the funding he brings with him has been seismic for the sport and, by extension, for Hearn and his fellow A-list British promoters Frank Warren at Queensberry and Ben Shalom at Boxxer.

Al–Sheikh is now arguably boxing’s most powerful figure, but he is also one of its most divisive. The 44-year-old, who was the subject of a special investigation by The Athletic in April, is one of the closest friends and allies of Mohammed bin Salman, the controversial ruler of Saudi Arabia, which has faced multiple accusations of human rights abuses.

Turki Al-Sheikh has emerged as a huge force in boxing (Clive Brunskill/Getty Images)

Hearn has always been relaxed about the involvement of the Saudis in boxing, pointing out in previous interviews that Western brands have been marketing themselves there for many years and that the country wants to show that it is modernising. Hearn declined to comment on any specific claims around Al–Sheikh when contacted after the interview by The Athletic.

In the interview, he did admit to surprise at how long Saudi interest has sustained given that, in his words, “financially, it just doesn’t really work. But these are very different people and the exposure that it’s creating for Riyadh Season and Saudi Arabia puts a different kind of value on it to anyone else in a normal situation.

“If you were an investment fund that said, ‘We want to make a play in boxing’, you couldn’t consistently lose this amount of money. But the losses for them are justified by the noise that it’s creating for tourism and the country. It’s just a case of how long does that last?”

The Netflix documentary series about Hearn and his company, Matchroom: The Greatest Showmen, gives viewers a glimpse of the chaotic, unruly world that is professional boxing. It includes an insight into the new ruling order, with Hearn seen responding to late-night calls from Al-Sheikh to attend meetings that run into the early hours.

Those calls can come at any time, Hearn has learned. Last summer, he was on the beach with his family, and waiting for what he knew was an important call from Al-Sheikh. He had waited for hours before eventually ceding to his kids’ pleas for him to join them for a swim in the sea.

“I was only going to be 10 or 15 minutes, so I put my phone down. Sod’s law, when I came back, there were about eight missed calls and voicemails: ‘He needs to speak to you now’. And then a voicenote from Turki saying, ‘I’m trying to reach you. Where are you?’.

“I said, ‘I’ve been waiting for five hours, I just went in the sea for 10 minutes!’”

He says he doesn’t mind being at Al-Sheikh’s beck and call, or waiting in his hotel for five hours for a 20-minute meeting, because he knows where it can lead. Hearn says he’d even clean Al-Sheikh’s shoes if he had to, and, while he’s joking, you wonder whether there may be a grain of truth in it.

After all, his job, he says, is “to make money. My job is not to sell my soul, but everything that I’ve done with him, whilst sometimes being a pain in the a***, has actually been very enjoyable and actually quite amazing in terms of its level and the experience. I like spending time with him, he’s a unique character; very driven, very smart, and he absolutely loves boxing.”

What Hearn loves, alongside money, is the lack of procrastination in boxing’s new order. He talks of going to Saudi Arabia to meet with Al-Sheikh and being wowed at the number of deals done across multiple sports within the space of 90 minutes. “And this is just me – he’s having 50 meetings like that a day.”

What Hearn loves less, but has had to adjust to, is losing some element of control to a man who not only makes decisions quickly, but acts on them with equal haste. “This is why I don’t think Dana (White) and those guys will enjoy working with him,” warns Hearn, referring to the entrance of the UFC president and the UFC’s parent company TKO into boxing with promotional company Zuffa Boxing, which has Al-Sheikh as a deep-pocketed partner. “Because he’s gonna do whatever he wants to do.”

Hearn admits working with Turki Al-Sheikh can be challenging (Mark Robinson/Getty Images)

Hearn’s examples paint a picture of a man who’s only working to one timeline: his own. “We might have a plan in place for how we will promote an event: when we’d put tickets on sale, when we’d drop the undercard etc. Then he’ll just say, ‘I want to announce the fight’ and tweets it.

“Then he’s asking, ‘When can we get tickets on sale?’. And I’ll say, we’ll have a build-up, we’ll have a pre-sale next week. ‘No’, he says. ‘Let’s go on sale tomorrow’. And he’s tweeted: ‘Tickets on sale, tomorrow’. It’s like, f******’ hell, mate. But that’s how it is. And he’s never gonna change. You have to understand that if you’re gonna work with him, that’s how it’s gonna be.

“I’m still humble enough to know that if I’m making money, the fighters are making money, I’m gonna do as I’m told. And I don’t mind saying it. Some people can’t say that. It doesn’t mean that I’ll do anything, but if it’s stuff like that, you accept, if you want the money, this is how it’s gonna be.”

Even Hearn’s strongest critics will find it hard to deny that he is good at what he does. But what exactly is that?

Ask him and he will say it’s telling (and selling) stories; creating interest around fighters and events. He’s surprisingly open in saying that, actually, boxing does not always rate that well when it comes to the live broadcast. “It’s a sport built off interaction, confrontation and controversy,” he says. “And actually, the value of boxing is beyond the live broadcast. As a business, it’s not always the most profitable or successful. But what it does do is create a huge amount of digital noise.”

When Matchroom’s fights were broadcast exclusively on Sky Sports, Hearn says he was told that in terms of interaction on digital platforms, boxing was a clear second, behind only Premier League football. Yet from a ratings perspective, it was much further down the order. “So it’s my job to create that interest; there’s a huge amount of storytelling. The product is obviously the most important thing, but I’ve learned that the ability to sell and transfer your emotions into the customer and fan is also very important.”

That’s as far as the show goes, but what of the promoter’s role regarding their fighters? Hearn clearly builds close ties to some of the boxers he promotes, especially those like Anthony Joshua and Katie Taylor, who he will likely promote for the entirety of their professional careers. How does that personal relationship and the natural desire to protect the fighter and ensure they come out of boxing healthy enough to enjoy the rest of their lives combine with the desire to make them (and himself) as much money as possible?

Hearn has a close bond with his fighter Anthony Joshua (Richard Pelham/Getty Images)

“Obviously, you’ve got to try to protect the fighter,” says Hearn. “But that’s also the job of the trainer and the manager. I know boxing inside out, but as a team, that’s more their role than my role. I’m not saying that we don’t protect the fighter, but a trainer’s job is to make sure that they’re in the right fight. They know things that we don’t. They may know that sparring didn’t go well or maybe his chin’s not as good as it used to be.

“We have to present the opportunities to the fighter. And every fighter’s situation is very different. Every ability is different. Every dream is different. Every work ethic is different. You’ve got to blend all that in.”

There have been a few times during his career when Hearn recognises that perhaps he made the wrong move. He mentions Kell Brook, who jumped two weight divisions to challenge the undisputed world middleweight champion Gennady Golovkin in 2016. The fight was stopped in the fifth round when Brook’s trainer, Dominic Ingle, threw in the towel. A few days later, it emerged that Brook had broken his eye socket in the second round and fought on with blurred vision.

Hearn has explanations for his decisions, ranging from Brook’s lack of fight options at welterweight to helping him capitalise on “a bit of a cash-in” while he still could, but it is a source of regret.

Then there is Hearn’s decision to match Anthony Joshua with Andy Ruiz Jr as a late replacement for Joshua’s original opponent, Jarrell Miller, who had failed drugs tests, in June 2019. Joshua went into the fight against Ruiz as the odds-on favourite, but was sensationally dropped four times before suffering an eventual seventh-round stoppage defeat; the first loss of his professional career.

“Did we choose the right opponent on four weeks’ notice? Probably not,” says Hearn. “At that point, I do have to lean to (Joshua’s trainer) Rob McCracken and AJ and the team and say, ‘These are the options on the table, this is a very marketable fight. We’ve sold out Madison Square Garden’.

“The fact that we got the rematch and he made by far the biggest payday of his career and we won makes it all OK. Sometimes you make a decision that feels right at the time. But when you look back in hindsight, maybe it wasn’t. As long as you and the team feel it’s right at the time, I don’t think you can ever really regret it.”

At the beginning of this year, Hearn made the decision to give up his X account and its 1.1million followers, handing over the reins to his team so that they can still make use of its reach for promotional purposes.

“I’d be scrolling it all night to get the opinion and the feel, but the problem is it’s no longer the opinion and the feel, it’s just this hate, negativity and toxicity,” he says. “I probably let it get to me too much. I look at my kids and the algorithm and stuff that’s coming in, and it’s frightening, really.”

Chris Eubank Jr’s bout with Conor Benn on Saturday is huge for British boxing (James Fearn/Getty Images)

Hearn will always have critics, of course. One of his biggest will be inside the ring on Saturday night; Eubank Jr having on more than one occasion referred to him as a “scumbag” and refusing to let him speak at press conferences ahead of both fights with Benn.

Those “running battles”, as Hearn calls them, are more within his comfort zone, however – all part of the “hyperbole of noise” that he has spent the past 15 years helping to create.

“Boxing is very different (to other sports),” he says. “If I worked in cricket, I don’t think I’d be out there in quite the same way.”