This article is part of our Forever Forward series, showcasing the ways Formula 1 is innovating for the 2026 season.

One hand on the wheel at 190mph. Shooting into and up the famous Eau Rouge climb at Spa-Francorchamps. Disaster potentially seconds away.

For Renault driver Robert Kubica and others, driving a Formula One car in 2010 had become significantly harder.

Kubica was using Renault’s own version of a system developed by a rival that boosted a car’s speed in a straight line, using a clever aerodynamic trick that became the forerunner to the Drag Reduction System (DRS) overtaking aid.

As the 2025 F1 season ends, DRS will be phased out of F1’s collective lexicon. DRS, the overtaking aid that involves a slot opening in a car’s rear wing to shed drag and boost speed on straights, is not included in the new car design rules coming for the 2026 season. The new cars will instead automatically shift into a low-drag configuration on straights without any driver input.

And so F1’s 15-season era of DRS-assisted passes will end — one dominated by talk of how the system can often make passes too easy for drivers. This is an age that began in the 2011 season, dominated by Red Bull driver Sebastian Vettel. But its legacy, and that of its precursor that arrived the previous year, in 2010, will live on.

The F-duct was developed by McLaren, then running Lewis Hamilton and 2009 world champion Jenson Button as its drivers.

“It was a fantastically elegant solution to a clear loophole in the regulations,” Paddy Lowe, McLaren team engineering director at the time, told Autosport magazine in 2013.

The F-duct’s origins stretched back a year earlier, to 2009, as McLaren was conceptualizing the system. By then, F1 fans, the championship’s organizers, and its protagonists had long been debating how to improve the sport’s racing show. This stemmed from the many processional races of the early 2000s, and a significant car design rule change for 2009 that hadn’t worked.

Various aerodynamic solutions had been proposed by F1’s teams and rulemakers to reduce the dirty air factor inherent in racing cars running complicated front and rear wings. This makes passing much harder, even when drivers run in close formation, as they lose stability and momentum.

Eventually, F1 would settle on the combination of fragile tires and significant straight-line-speed-boosting DRS as the main ways to increase overtaking from 2011 to 2025. That’s even as engine and aero rules changed through that period.

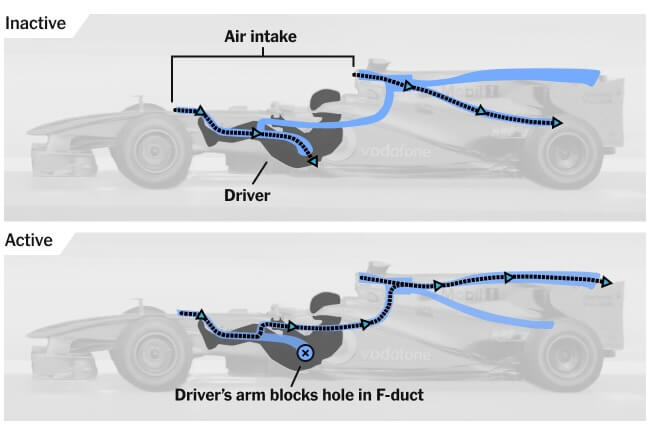

McLaren had the F-duct fitted to its MP4-25 car in 2010 pre-season testing. The system utilized a bespoke series of pipes running through the car and its cockpit, and then the air passing through this piping was manipulated to provide the speed boost.

Around this, McLaren had added a small scoop to the top of the car’s nose section in front of the cockpit — akin to a snorkel (pictured below).

Jenson Button during qualifying at the 2010 Monaco GP, with McLaren’s F-duct on the nose of his car. (Vladimir Rys / Bongarts / Getty Images)

Generally, this fed a pipe that went into the cockpit around the driver’s arms and lower body, but when they moved and covered a hole in the pipe, the air would bypass the car’s lower rear end and ultimately divert airflow that was being taken in from the air box above the driver’s head. This would otherwise cool the engine, using a different set of pipes McLaren connected to its new ones.

The redirected air was passed out of another new slot in the McLaren’s rear wing. This “stalled” the wing, disrupting the airflow over its lower element and so reducing the downforce that pushes a car into a track. The wing shedded much of its drag, so the car moved faster through the air when the system was active.

During the 2010 season, Hamilton and Button would cover the cockpit pipe hole by moving their left elbow around. At the end of that campaign, McLaren engineers revealed that this occasionally had them complaining about shoulder pain from that extra movement in the cramped environment.

The F-duct’s name stemmed from the nose scoop sitting where the F of the logo of team sponsor Vodafone was placed at this point of the car’s livery. Internally, McLaren called the system the RW80.

How the F-duct system worked on the McLaren MP4-25. Illustration: Drew Jordan / The Athletic; Clive Mason / Getty

“It was actually an awful lot of hard work,” then McLaren chief engineer Tim Goss said at the 2010 Autosport Awards, of getting the F-duct functioning. “We had a pretty crazy idea and (had) to turn that into reality.”

The F-duct made the MP4-25 potent in a straight line all through 2010, but the best example of how it boosted McLaren came at that year’s Italian GP, where it played a crucial role in the team’s result.

Button ran an unusually large rear wing for the Monza track and its many straights, where extra drag is heavily penalized in additional lap time, as cars move more slowly through the air as a result.

Using the F-duct, Button was quick enough down the straights to stay in contention despite the extra drag of his bigger wing, and with this, he was rapid through Monza’s few higher-speed corners. Button qualified second and fought Ferrari’s Fernando Alonso hard for the win.

Hamilton, running a typical low-drag Monza rear wing, which was therefore much smaller than his teammate’s, qualified further down the pack and was eliminated in a first-lap crash. He came to regret his setup decision, including it in one of several “mistakes” he made that weekend.

McLaren’s rivals had been quick to see the F-duct’s potential. It was considered to gain up to 0.5 seconds per lap compared to cars running without one. The Sauber squad was the first to get a copy onto its C29 car at 2010’s second round in Australia. Soon enough, Ferrari, Mercedes, and Renault were trialling their own systems.

Even Red Bull, which ultimately triumphed in the drivers’ championship with Vettel in 2010 thanks to its potent exhaust-blown double diffuser design, worked hard to get an F-duct copy working. The exhaust-blown diffuser, which massively increased downforce by having the exhaust gas blow directly into it, was 2010’s other big F1 tech innovation.

F1 car design great Adrian Newey, then Red Bull’s technical director, said in 2013 that Red Bull was “lucky” its car already had space for the F-duct pipes. But McLaren’s other rivals were struggling with their replicas around this explanation. This was because chassis designs are frozen once submitted to the FIA at a season’s start — an official process called homologation.

They therefore had to retrofit F-duct pipework around tight bodywork that had not been designed with such a system in mind. But the F-duct name stuck regardless of which car it was fitted on.

Jenson Button walks past his MP4-25 and that of Lewis Hamilton after qualifying at the 2010 Belgian Grand Prix. (John Thys / AFP / Getty Images)

“You get used to it quite quickly and not operating it seems harder than actually operating it, because it becomes automatic and you just put your hand down there and close the hole,” Vettel said of the F-duct after winning the 2010 European GP in Valencia.

“I think many drivers will have the same opinion about the system. It was a very smart idea; it’s a big benefit if you manage to set it up right, but obviously, you don’t have your hands on the steering wheel all the time. You get used to it, but it’s not the most comfortable thing.

The teams did differ in how their drivers would activate the F-duct to stall rear wings. And here is where the danger element really became an issue.

While Red Bull had worked to make its system work like McLaren’s, without the driver taking their hands off the steering wheel, Ferrari was the first to have its racers drive one-handed at specific points of a track, with the other hand covering the cockpit pipe holes.

Alonso was visibly doing so for the first time in competition at his home race in Spain, 2010’s round five. Three months later came the shocking sight of Kubica doing likewise through Eau Rouge/Raidillon. The F-duct could be used in corners if a team wanted, unlike DRS, which sheds too much downforce to be safely used in such circumstances.

“McLaren’s F-duct is intelligent and opens new ways,” Newey told Gazzetta dello Sport in April 2010.

“However, I’m worried about the safety aspect. The system works by stalling the rear wing and relieving the load. To force a driver to make a sudden movement to change normal load conditions (concerns) safety.”

Such concerns played a key role in why the F-duct was only seen in one F1 season. Because while Ferrari was adding its version at the 2010 Spanish GP, the Formula One Teams’ Association (FOTA) had already agreed its use would be discontinued for 2011. FOTA united the teams as a body for rules negotiations with F1 and the governing body, the FIA, between the 2008 and 2014 seasons.

As the pictures of one-handed driving were emerging in Spain, FOTA was already discussing and approving DRS as a replacement. After all, it’s a much more potent way of shedding drag, by as much as 10 times than was lost with F-duct, and therefore much better for increasing overtaking.

McLaren fought to keep the system devised by a group of its engineers headed by Mike Brown — which had its roots in Cold War aircraft design — being dismissed. But it ultimately accepted a FOTA majority vote on the issue, with then McLaren team boss Martin Whitmarsh always keen to keep the peace between the teams while he headed the body, as he did between 2009 and 2014

The cost of other teams redesigning chassis parts was also cited as a major reason to abandon the F-duct, with the DRS system considered much less complex.

“We are very proud of our guys who thought of it. Compared to some other things, it’s a very low-cost technology to apply, and there are a number of reasons why something like that is good for the sport,“ Whitmarsh told a Vodafone teleconference a few days after the F-duct ban was agreed in Spain.

“It just needs a bit of ingenuity. Personally, I’m a bit sad about it.”

A month later, in June 2010, the DRS concept was officially incorporated in F1’s rules for 2011, and these were signed off by the FIA.

Although the DRS will also disappear from F1, its legacy will remain. From 2026, the cars will still shed drag on straights via more moveable aerodynamic parts, but it will be automatic, as a process called “straightline mode” is activated.

The lineage from the F-duct through to DRS and 2026’s straightline mode is established. At each stage, the driver has become less involved — their bodies simply charged with racing at 200mph, not enacting aerodynamic principles at the same time.

The Forever Forward series is part of a partnership with SAP. The Athletic maintains full editorial independence. Partners have no control over or input into the reporting or editing process and do not review stories before publication.