Listen to this article

Estimated 5 minutes

The audio version of this article is generated by text-to-speech, a technology based on artificial intelligence.

Every few years, Glooscap First Nation asks its members for feedback: where do they want to invest their money?

In 2017, renewable energy entered the conversation.

“It wasn’t the highest scoring, but it made it into the top three for the first time,” said Michael Peters, CEO of Glooscap Ventures, the community’s economic development arm.

“So that was kind of our, you know, green light to start looking at renewable energy opportunities,” Peters said in an interview.

Glooscap started small, with an array of solar panels on a commercial building. Peters said he hoped to cut down on energy costs and reduce Glooscap’s carbon footprint.

His ambitions have since grown, and so has the community’s endorsement. He said investment in renewable energy was the No. 1 priority in the latest round of community consultation.

Now, Glooscap is frequently connected with renewable energy projects in Nova Scotia as an investor or owner — as are many other Mi’kmaw communities. The same is true of other First Nations and energy projects across the country.

The trend is thanks, in part, to a push from multiple levels of government for Indigenous participation in major projects as a form of economic reconciliation. And equally important is the appetite from communities and their leaders. Case in point: Glooscap.

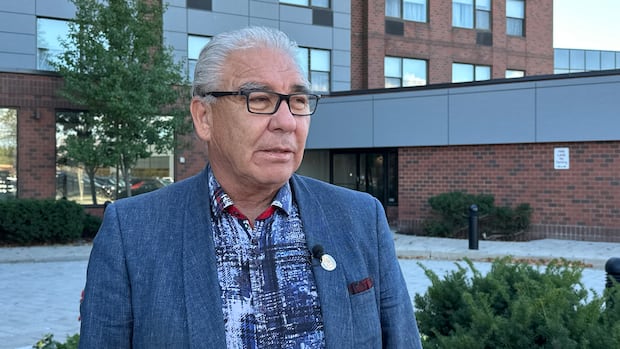

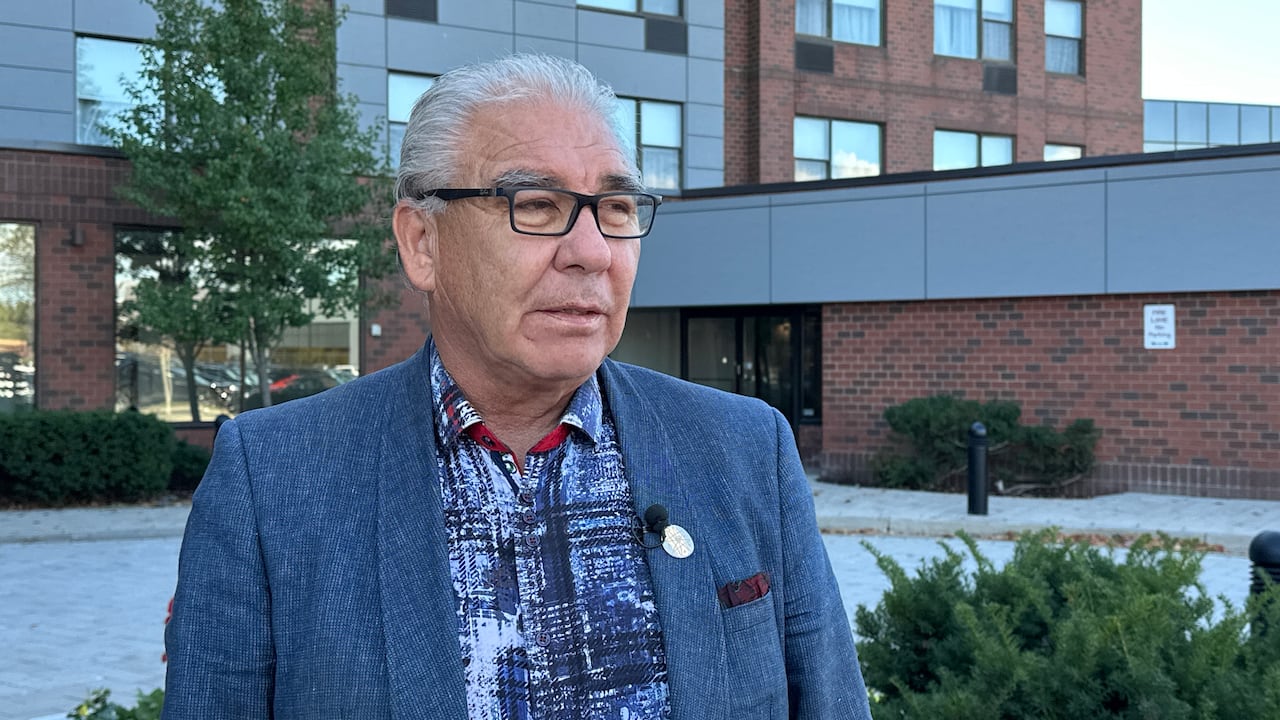

Glooscap Chief Sidney Peters says he wants to ensure the Mi’kmaw perspective is integrated into new energy projects. (David Laughlin/CBC)

Glooscap Chief Sidney Peters says he wants to ensure the Mi’kmaw perspective is integrated into new energy projects. (David Laughlin/CBC)

Peters said further solar installations have made many of Glooscap’s community buildings and businesses energy self-sufficient. Now the community is focusing on renewable energy production as an enterprise, with the goal of turning it into a significant part of the business portfolio alongside fisheries and gaming, he said.

The work Glooscap is doing on renewable energy was recognized this fall by the Canadian Renewable Energy Association (CanREA), which named Glooscap Ventures the Indigenous Clean Energy Company of the Year.

Jean Habel, a senior director with CanREA, said Glooscap won the prize because it’s “really poised to be part of the energy transition.”

More than dollars and cents

Glooscap is now a majority partner in two wind projects that are under development. Neither is generating power yet, but one has a deal to sell electrons to Nova Scotia Power for general use on the grid and the other has a deal to sell power to big consumers through a provincial program called Green Choice.

Glooscap is also part of a Mi’kmaw agency — a collective of all 13 Mi’kmaw nations — that is going big on renewable energy.

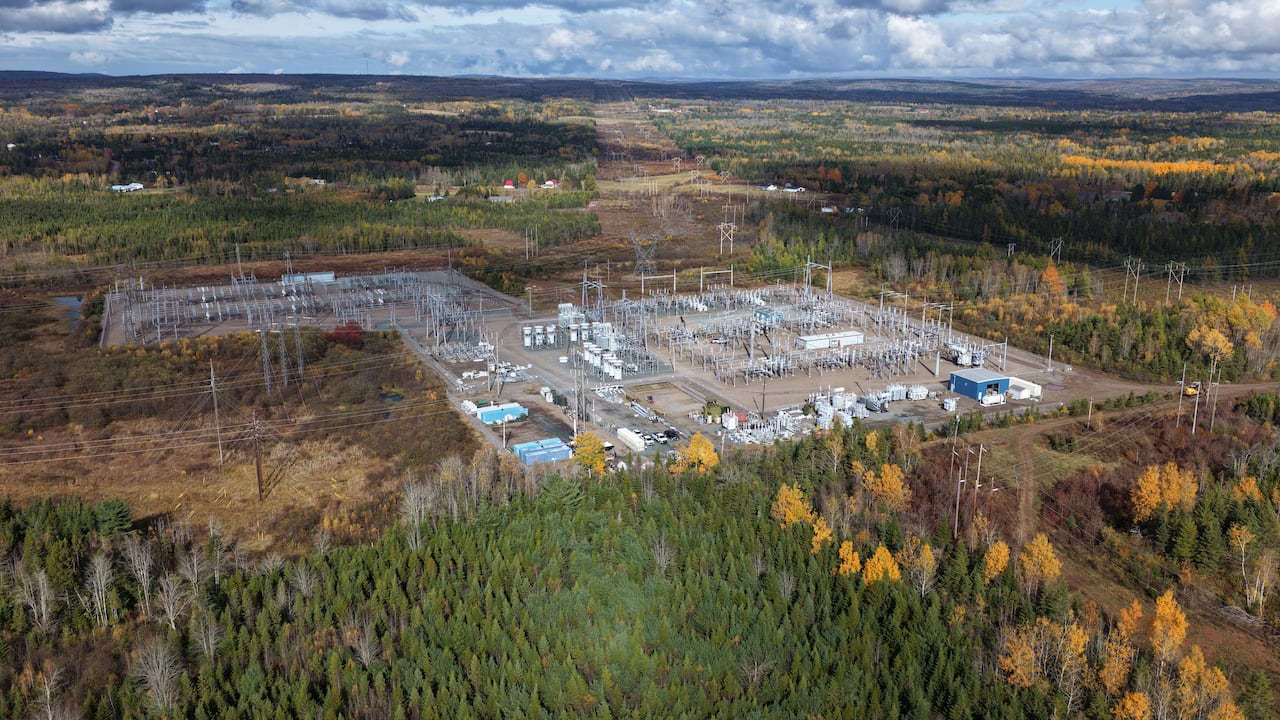

The Wskijinu’k Mtmo’taqnuow Agency (WMA) is a majority owner of two wind projects and several battery storage facilities — all of which are in the planning or development phases — and it’s set to have a large stake in the Nova Scotia-New Brunswick intertie, which Nova Scotia says is a critical part of its clean power plan.

The Nova Scotia Energy Board approved the financing arrangement for the intertie this week, quashing some earlier concerns about Nova Scotia Power’s potential profits.

“Further, the involvement of the WMA … advances economic reconciliation with the province’s Indigenous peoples,” the board noted in its written decision.

The transmission lines leading away from the Onslow substation will be doubled in the coming years as part of a major project to improve the connection between Nova Scotia and New Brunswick’s grids. Glooscap and other Mi’kmaw nations are equity partners in the project. (Brian MacKay/CBC)

The transmission lines leading away from the Onslow substation will be doubled in the coming years as part of a major project to improve the connection between Nova Scotia and New Brunswick’s grids. Glooscap and other Mi’kmaw nations are equity partners in the project. (Brian MacKay/CBC)

Glooscap Chief Sidney Peters, dad to Michael Peters, said diversifying his community’s revenues has been a long-time goal for him. But he said getting into renewable energy is about more than dollars and cents.

The chief said he wants to see Mi’kmaw values integrated into any new industrial endeavour.

“I want to ensure that the projects that we do are good, clean projects, and we’re not abusing the environment,” he said in an interview.

Government incentives

It wasn’t a formal requirement, but Mi’kmaw ownership has been an element of every successful bid made so far to the Nova Scotia government for projects that will factor into the 2030 clean energy plan.

At the federal level, the Trudeau government introduced funding streams specifically targeted at Indigenous-led clean energy projects, which brought in more than $125 million to projects in Nova Scotia, including some of Glooscap’s.

The general principle is continuing with the Carney government, which has added Indigenous organizations to its Clean Electricity Investment Tax Credit. Updates to the tax credit are part of the budget that’s currently moving through Parliament.

Additionally, the Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB) offers favourable financing to projects that have Indigenous partnership or ownership.

Sashen Guneratna, a director with the CIB who leads its clean power sector, recently said at a renewable energy conference in Halifax that Indigenous participation is essential to get the CIB’s interest.

“They have very strong and great ideas about how these projects should work,” he said.

But SWEB Energy, Glooscap’s partner in its two primary wind projects, said joining forces with First Nations is about more than getting points in a government procurement or tapping into financial incentives.

“Our thoughts are that First Nation communities should be at the core of [the renewable energy] transition if it’s of interest to [them],” said Jason Parise, SWEB’s director of wind development.

MORE TOP STORIES