In 2014, the term “polar vortex” burst on the scene across Canada and the U.S. as temperatures plunged. In some places, it was colder than it was on Mars.

Well, get ready to hear more about it. Forecasters say parts of Western and Central Canada are about to feel the effects of the phenomenon that brings frigid weather in the coming weeks. And it could move to Eastern Canada.

“The European [model], the latest one, is looking like a pretty impressive cold pattern setting up,” said Judah Cohen, a climatologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

“The cold is going to slide down east of the Rockies … you’ll hear about Calgary, definitely Winnipeg.”

Though the term became popular a decade ago, the fact is, a polar vortex is always around. It’s just that usually, it remains high in the north.

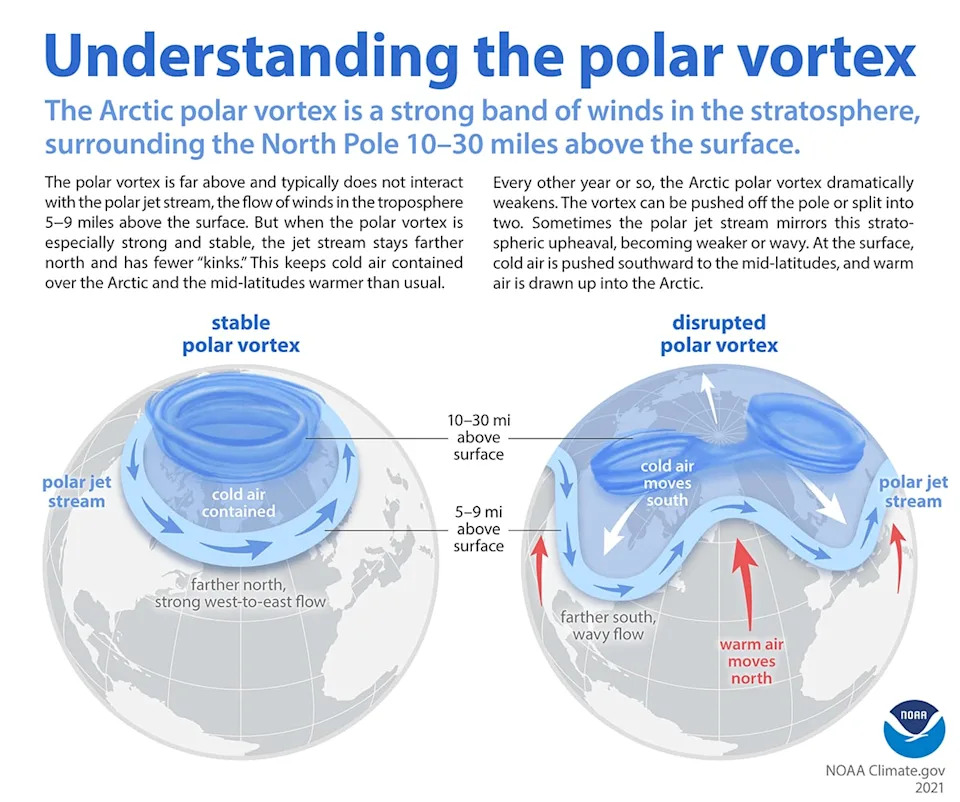

A polar vortex sits in the upper atmosphere, specifically in the stratosphere. If it’s stable, that’s where it remains. However, every once in a while in winter, it destabilizes and meanders farther south, bringing cold air to lower latitudes. It interacts with the jet stream in the troposphere, basically, where we humans live, and that’s what brings the colder-than-normal temperatures.

“Once every two years there is a disruption of the polar vortex. So you get very strong warming like tens of degrees Celsius in a few days, which is associated with a breakup or stretching or disruption of these winds,” said Michael Sigmond, a research scientist with Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC).

An illustration of what happens when the polar vortex is disrupted. Typically, as seen at left, it stays some 15 to 50 km above the surface and remains in the Arctic. But when it weakens, as seen on the right, it can get disrupted, interacting with winds closer to the surface and bringing cold air to lower latitudes. (NOAA)

Different kinds of polar vortexes

Not all polar vortexes are the same, Cohen explained.

One is called sudden stratospheric warming, where there is extreme warming in the upper atmosphere, roughly 30 kilometres above Earth. That disrupts the flow and brings it south.

“Sudden stratospheric warming gets everybody the most excited,” Cohen said. “It can have a big impact, not because of so much as the intensity, but its long duration.”

Then there are polar vortexes that split, and ones that just kind of stretch down over the south.

So which one is this?

The jury is still out, he said, though some believe that it will be a sudden stratospheric warming event, which, counter to its name, brings cold air down south.

“If it indeed materializes, it would be the earliest on record,” Sigmond said.

The U.S. side of Niagara Falls is shown beginning to thaw after the early January 2014 polar vortex event. (Nick LoVerde/The Associated Press)

Interestingly, Sigmond left Toronto for the more temperate climes of Victoria after the 2014 polar vortex chill.

“We moved in May, but I always say, oh, this was our goodbye,” he said.

Whether or not this will be a sudden stratospheric warming event or just a plain old polar vortex doing its thing, doesn’t really matter, Cohen said. It’s going to be cold.

But where will it go after affecting Western and Central Canada?

“Does it dive straight south or does it kind of move eastward?” Cohen said. “That’s probably the biggest question.”