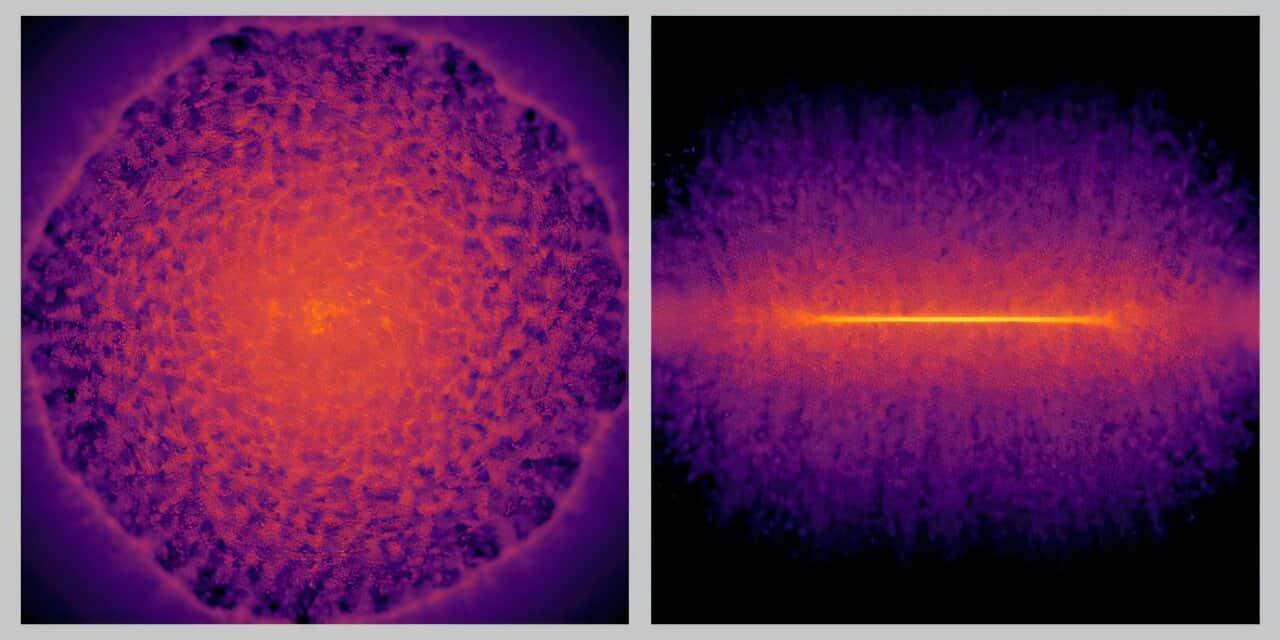

Head-on (left) and side-view (right) snapshots of a galactic disk of gas. These snapshots of gas distribution after a supernova explosion were generated by the deep learning surrogate model. Credit: RIKEN

Head-on (left) and side-view (right) snapshots of a galactic disk of gas. These snapshots of gas distribution after a supernova explosion were generated by the deep learning surrogate model. Credit: RIKEN

Astrophysicists have always dreamed of running a simulation of the Milky Way that could track every single star—each orbit, flare, and explosion—without cutting corners. Now, a team in Japan has finally done it.

Using artificial intelligence, researchers at the RIKEN Center for Interdisciplinary Theoretical and Mathematical Sciences, alongside collaborators from the University of Tokyo and the Universitat de Barcelona, have achieved the world’s first star-by-star simulation of our galaxy.

The results, presented this week at the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis (SC ’25), push the boundaries of what even the fastest supercomputers can handle.

“I believe that integrating AI with high-performance computing marks a fundamental shift in how we tackle multi-scale, multi-physics problems across the computational sciences,” said lead author Keiya Hirashima of RIKEN.

Cracking the billion-particle barrier

Until now, modeling galaxies has always required compromise. Simulations could either include the detailed physics of individual stars, or the grand-scale structure of an entire galaxy—but not both. A Milky Way–sized simulation would typically lump clusters of hundreds of stars into single “particles” to save time and computing power.

That bottleneck came from the wildly different time and spatial scales involved. A supernova might unfold over a few years, while galactic evolution plays out over billions. The superheated gas of an explosion, measured in millions of degrees, interacts with cold molecular clouds just ten degrees above absolute zero. Keeping track of both phenomena required timesteps so small that even the world’s fastest supercomputers would need decades of real time to finish.

In the team’s paper, Hirashima and colleagues describe how they broke what they call the “billion-particle barrier” by running a hybrid model that merged physics-based simulation with a deep-learning “surrogate” model.

Trained on high-resolution simulations of supernova explosions, the model learned how expanding clouds of hot gas behave over 100,000 years. That knowledge let the AI handle localized bursts of activity while the main simulation continued tracking the galaxy’s overall dynamics.

“This achievement also shows that AI-accelerated simulations can move beyond pattern recognition to become a genuine tool for scientific discovery—helping us trace how the elements that formed life itself emerged within our galaxy,” Hirashima added.

The supercomputer galaxy

To pull this off, the researchers harnessed Fugaku, Japan’s powerhouse supercomputer, alongside the University of Tokyo’s Miyabi system and Flatiron Institute’s Rusty cluster. On Fugaku alone, they used 148,900 nodes, equivalent to over 7 million CPU cores, running a total of 300 billion particles. That’s much more than any galaxy simulation before it.

The AI surrogate handled the local fireworks: each time the model detected a star on the verge of exploding, it sent the surrounding region to a set of “pool nodes” for the neural network to process independently. The AI predicted how gas and dust would evolve in the next 100,000 years and fed those results back to the main computation—without slowing the whole system down.

In a conventional setup, simulating 1 million years of galactic time might take 315 hours. With the new method, it took just 2.78 hours. That means simulating a billion years—roughly the span of a spiral arm’s slow rotation—can now be done in about 115 days, instead of 36 years.

The simulation scaled smoothly across tens of thousands of processors and maintained efficiency even at the highest resolution. In total, it achieved a 100× speedup and used 500× more particles than any previous galaxy-scale model.

A new kind of cosmic microscope

Because this AI-assisted framework bridges massive differences in time and space, it could be applied to other complex systems—from predicting climate dynamics to modeling turbulent ocean flows or even plasma physics.

“The issue of small timestep is common in any high-resolution simulations, not only in galaxy simulations,” the authors wrote. “The technique of replacing a small part of simulations with deep-learning surrogate models has the potential to bring benefits in various fields.”

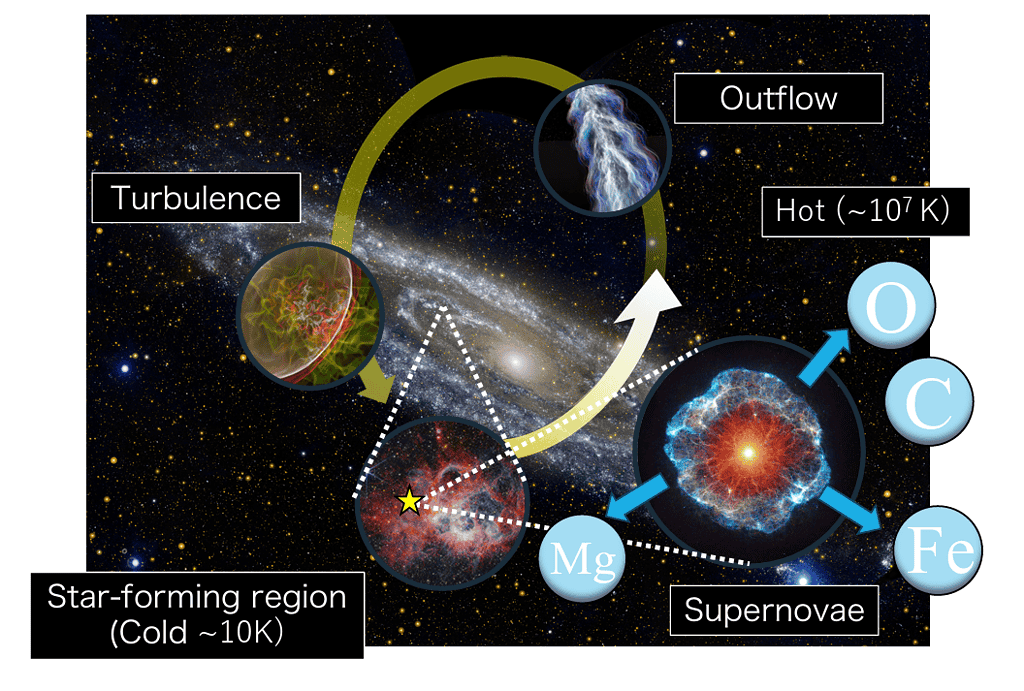

Material circulation in a galaxy. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech, ESA, CSA, STScI.

Material circulation in a galaxy. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech, ESA, CSA, STScI.

For astrophysics itself, the ability to follow each star’s story offers a map of how matter is recycled through generations of stellar births and deaths. Inside the study, a NASA-sourced diagram shows this cosmic cycle of supernovae seeding new stars with oxygen, carbon, magnesium, and iron. In a sense, every simulated explosion now helps reveal how the Milky Way built the ingredients for planets like Earth and the life that arose on them.

The researchers’ next steps involve scaling the model further, possibly including the effects of cosmic radiation, black hole accretion, and intergalactic gas inflow. With AI now woven into the very fabric of simulation, galaxies may soon become not just subjects of study but living laboratories where the universe’s history can be replayed in silico.