Joshua Lederberg, Nobel laureate and president of Rockefeller University, is well known in biology circles. Not so his wife, Dr. Esther Lederberg – whose name was drowned in the annals of the history of biology. And yet her work is critical to the practice of cutting-edge medicine and serves as a scaffold for modern genetic discoveries.

Joshua Lederberg won the Nobel Prize for discovering that bacteria can mate and exchange genes through bacterial conjugation, sharing the prize with George Beadle and Edward Tatum. Tatum had hired Esther as his teaching assistant, where she was instrumental in Tatum’s success; however, her own work was consigned to oblivion, at least in terms of recognition. Among her discoveries, Esther isolated the Lambda phage, a bacteriophage that infects E. coli, a discovery crucial to modern understanding of gene regulation and DNA replication and instrumental in developing genetic engineering tools. The lambda phage is also an important vector for delivering gene therapy for bacterial infections, and is currently being investigated as a treatment vector for cancer.

Despite these and other stellar discoveries, and unlike other co-Nobelist spouses, like Mme. Curie and Gerti Corie, Esther’s career and discoveries were eclipsed by her husband’s.

Never offered a tenured teaching spot, textbooks either ignore her work or attribute her accomplishments to her husband. Even as the role of women became more recognized, hers was downplayed. And yet, without her contribution to the field of genetics, modern medicine would have been short-changed.

The seeds and shoots

Born into an impoverished Orthodox Jewish household in 1922, Esther Miriam Zimmer learned Hebrew as a child and parlayed her knowledge into conducting the family Passover Seder (services), to the delight of her grandfather. Her father, David Zimmer, immigrated to the US, settling in the Bronx, where he ran a print shop.

Science was not on her radar then, and she initially considered studying French or literature before switching to biochemistry, against the advice of her teachers, who felt that, other than in botany, women struggled to get careers in the sciences (likely because of the pioneering work of Nobel laureate Barbara McClintock). Esther graduated from Hunter College, a pre-eminent women’s college of the day (which also graduated Nobel Laureates Rosalyn Sussman Yallow and Gertrude Elion), before winning a fellowship at Stanford University, where she earned a Master’s Degree in genetics. The fellowship was financially negligible, so, occasionally forced to eat frogs’ legs left over from laboratory dissections, she supplemented her income with free accommodation in exchange for washing her landlady’s clothes.

The Discoveries Begin

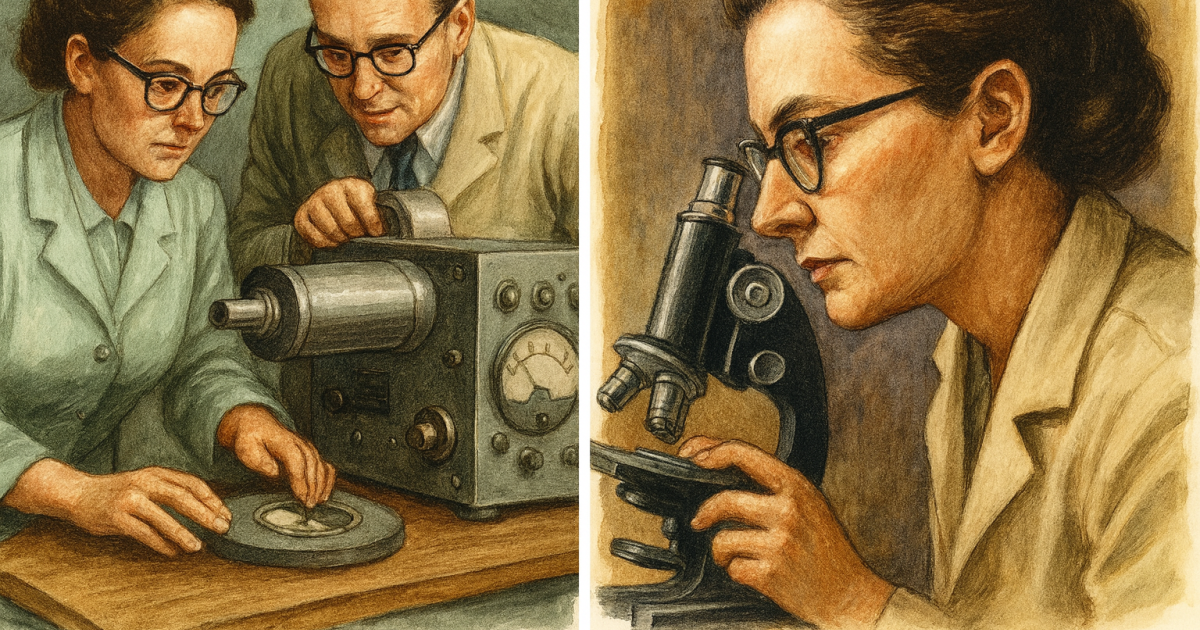

While at Stanford, she met her husband-to-be when he wrote to ask her about her work on the red bread mold Neospora crassa, researchhe later capitalized on. In fact, her seminal paper on the topic is heralded on his website. She married Joshua and followed him to the University of Wisconsin, where he was appointed to the faculty. There, Esther began her doctorate, which she earned in 1950, supported by a United States Public Health Service Fellowship. It was there that Esther discovered the lambda phage and the E. coli fertility factor. This F-factor, the first plasmid discovered, is a bacterial DNA sequence that fosters gene transfer to other bacteria, a process called conjugation.

At Wisconsin, she worked and published with Joshua on various projects, including the genetic mechanisms of specialized transduction, which later earned him the Nobel Prize. Jointly, they devised the first successful implementation of replica plating, which addresses the problem of reproducing bacterial colonies en masse, and is used to isolate and analyze bacterial mutants and track antibiotic resistance. Biographer Rebecca Ferrell believes that Esther invented the replica plating technique, inspired by her father’s printing press, which involved pressing a plate of bacterial colonies onto sterile velvet, then stamping them onto plates of different media, depending on the traits the researcher wished to observe. In 1956, the pair were honored by the Society of Illinois Bacteriologists with the Pasteur Medal for this and other work.

Sentenced to Anonymity

When Joshua returned to Stanford as head of the genetics department in 1959, Esther came along. Women faculty at Stanford were a rarity in those days, and Esther, along with two other women, had to petition the dean for greater representation. Eventually, she was appointed research associate professor, an untenured spot, and then senior scientist. After she and Joshua divorced, things got worse. In 1974, she was essentially demoted to a short-term, renewable adjunct professorship, dependent on her securing grant funding.

Some accounts suggest that after her foundational discoveries of the F factor and the lambda phage, Joshua stopped her from conducting additional follow-up experiments. By the time he won the Nobel Prize in 1958, the research centers that recruited him saw Esther as his wife and research assistant rather than an independent scientist, and, slowly, he, too, began to marginalize her.

The Matilda Effect

“What [Esther] Lederberg did was spend decades investigating the way micro-organisms share genetic material, trailblazing work at a time when scientists had little sense of what DNA was. So did her first husband…Yet far more people have heard of him than of her, a disparity that some experts attribute to a phenomenon known as the Matilda Effect. … the bias that has led to female researchers being “ignored, denied credit or otherwise dropped from sight” throughout history.”

-Katy Steinmetz, Time Magazine

Esther cast Joshua’s early efforts to stymie her research in a more benign light, but hard evidence of discrimination against her persisted. In 1966, she was excluded from writing a chapter in Phage and the Origins of Molecular Biology, a commemoration of molecular biology. According to the science historian Pnina Abir-Am, her exclusion was “incomprehensible” because of her important discoveries in bacteriophage genetics.

Esther’s contributions were also overlooked by the Nobel committee. Instead, the credit for this and other discoveries, notably her replica plating, is given to her famous husband, or, at best, to Dr. and Mrs. Lederberg. In this respect, Esther is likened to Lise Meitner and Rosalind Franklin.

Postumous Post Script

By the time of her death, Stanford had engaged in some corrective history, elevating her posthumously to the rank of Professor emeritus and noting her role as director of the Plasmid Reference Center at Stanford Medical School, which she ran from 1976 to 1986.

“STANFORD, Calif. – Esther Miriam Zimmer Lederberg, PhD, professor emeritus of microbiology and immunology at the Stanford University School of Medicine, whose more than half-century of studies opened the door for some fundamental discoveries in microbial genetics.”

And yet, she was revered by her colleagues:

“She was one of the great pioneers in bacterial genetics. Experimentally and methodologically, she was a genius in the lab.” – Stanley Falkow, PhD, Professor in Cancer Research.