Biology professor Raffaela Lesch says racoons are beginning to show some physical traits of domestication, but it likely won’t happen for a few thousand years.

Toronto’s garbage-raiding mascot may be evolving in a way that is better suited to its biggest fans.

A new study found raccoons in cities are evolving based on their proximity to humans, developing shorter snouts that make them look cuter.

The study’s aim was to explore how human environments trigger traits of “domestication syndrome” in these masked mammals, as domesticated animals like cats and dogs commonly share anatomical and morphological traits like floppy ears, white patches, smaller brains and reduced facial skeletons.

Raffaela Lesch, assistant professor of biology at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock and the study’s co-author, called this the Neural Crest Domestication Syndrome hypothesis.

“We’re not agreeing that this is the perfect explanation, but it’s the best one we have so far that basically suggests that selection for tameness that these animals undergo when they coexist with humans might have an impact on the development when they’re embryos, and that basically alters all these traits that we see in domesticated animals,” Lesch said.

Researchers out of University of Arkansas at Little Rock combed through nearly 19,500 photos of the masked mammals, comparing the length the snouts between rural and urban raccoons across the United States in the process. Through this, they found a 3.56 per cent snout reduction in urban raccoons.

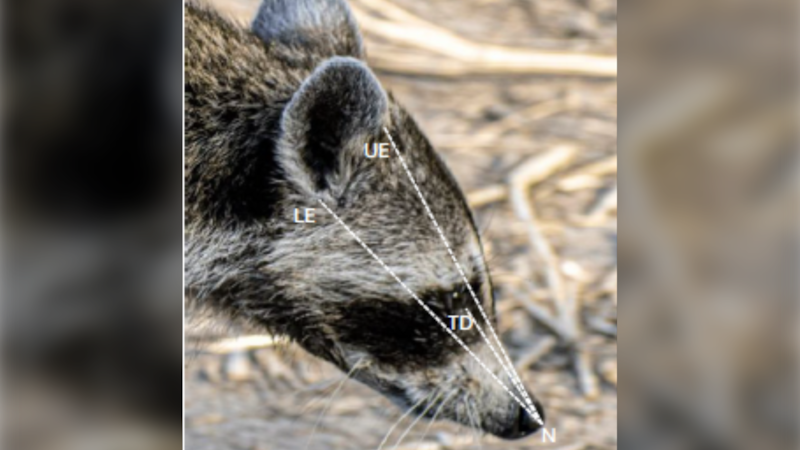

Raccoon snout measurement An example of the snout and skull length measurements researchers calculated for the study. (Frontiers in Zoology)

Raccoon snout measurement An example of the snout and skull length measurements researchers calculated for the study. (Frontiers in Zoology)

“I would expect that to hold truth across the entire population range,” Lesch said, when asked if the findings would also apply to Toronto’s trash pandas.

While the findings are interesting for Suzanne MacDonald, a York University professor who has been studying urban raccoons for more than 10 years, she has not seen the same sorts of changes in Canadian raccoons.

“In the United States, raccoons are hunted (sometimes for food) and that means there is ‘selection pressure’ on those raccoons, where the ‘cuter’, short-snouted animals may be less likely to be killed and thus more likely to survive and pass on their short-nosed genes to their babies,” MacDonald said in an email.

So, does a raccoon make for a great pet?

Even though raccoons may be looking more like cuddly critters, Lesch stresses the point of their study was not to say raccoons may fill the role as man’s next best friend.

“They’re not. We’re arguing that they (raccoons) might be in the beginning stages of domestication, which takes so many generations, like thousands of years,” Lesch said.

“We don’t have a pet sitting in front of us right now, this is still a wild animal that is adjusting to human environment and potentially on the pathway to domestication.”

Kerry Bowman, a bioethics and environmental ethics professor at the University of Toronto, underscores how raccoons make for difficult pets, pointing to their destructive qualities and propensity to bite.

Though Bowman has nothing against the raccoon, he says they don’t really provide a mutually beneficial relationship for humans as a pet in the same way that a dog or cat does.

“Dogs are tremendous, you’re bonding to humans and you’ve got a lot of emotional and psychological benefits. And, if you look at human history, the fact that dogs were kind of alarm calls at night was very useful to us,” Bowman explained.

“(Cats) really helped control rodent populations of rat and mice around people as well, so I don’t see with raccoons—I don’t see the reciprocity there.”

While they’re dubbed as Toronto’s mascot, Torontonians are barred from owning a raccoon as a pet, as the City of Toronto has listed them as a prohibited animal to keep (on a temporary and permanent basis).

The City of Toronto says they have received more than 17,000 service requests pertaining to raccoons this year, primarily for cadaver removal and injured or distressed raccoons.

Correction

A previous version of this article included a statement that said Canadians cannot hunt raccoons because they are a protected wildlife species. However, in Ontario, those with a valid small game or trapping licence can hunt raccoons at night.