A fossilized dinosaur embryo discovered inside a fossilized egg in southern China is reshaping scientific understanding of avian evolution. Preserved for more than 70 million years and left unexamined in a museum collection for over a decade, the embryo—nicknamed Baby Yingliang—has emerged as one of the most complete non-avian dinosaur embryos ever found.

What stunned researchers wasn’t just the pristine condition of the fossil, but the embryo’s curled position, which mirrors the pre-hatching posture seen in modern birds. This behavior, known as tucking, is controlled by the central nervous system and is considered vital for a chick’s survival during hatching.

The discovery, featured in iScience (Cell Press), presents the first direct fossil evidence of this posture in a non-avian dinosaur. The implications are profound: traits once thought to be exclusive to birds—instinctive, complex behaviors embedded deep in their embryonic development—may have originated in their dinosaur ancestors.

Once Forgotten, Now a Key to Evolution

The egg that housed Baby Yingliang came from a fossil trove unearthed during construction near the Shahe Industrial Park in Jiangxi Province, a site known for producing numerous Cretaceous-era specimens. Donated to the Yingliang Stone Natural History Museum in 2000, it sat largely ignored until 2015, when staff noticed bones peeking through a hairline fracture in the shell.

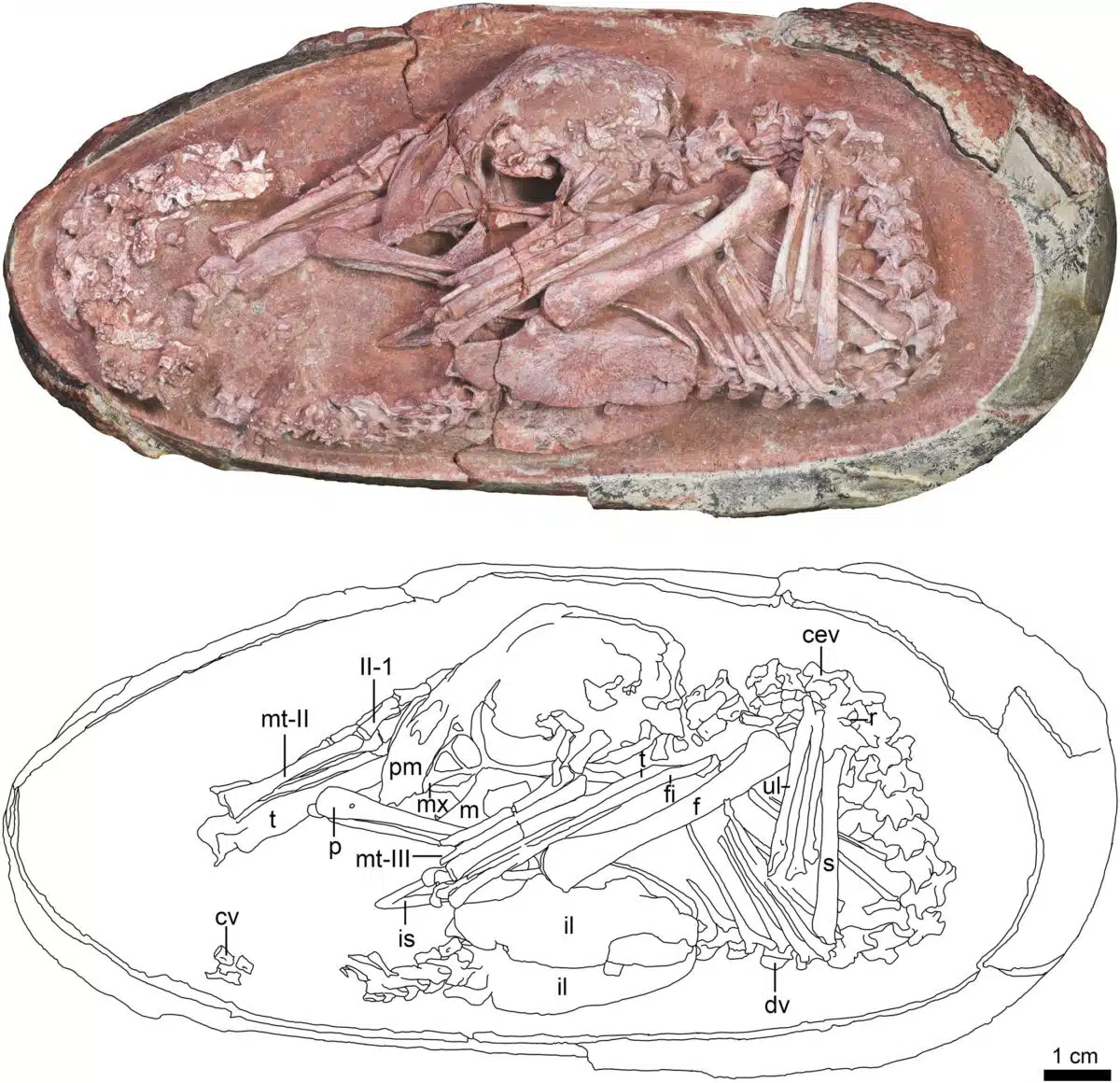

Oviraptorid embryo (Baby Yingliang) inside an elongatoolithid egg. Credits: Cell/Xing et al., 2021

Oviraptorid embryo (Baby Yingliang) inside an elongatoolithid egg. Credits: Cell/Xing et al., 2021

Detailed analysis revealed a remarkably preserved oviraptorosaur embryo—belonging to a group of feathered, beaked theropods closely related to birds. The embryo, curled within its 17-centimeter egg, displayed a tucked posture: head tucked toward the body, spine curved along the shell, limbs folded tightly. This arrangement had previously only been observed in bird embryos approaching hatching.

The research team, including scientists from China, the UK, and Canada, documented the fossil in high-resolution and compared it to bird embryos and other dinosaur finds. Their findings, published here, identified the same biomechanical pattern that ensures proper hatching in birds—suggesting the behavior predates avians.

Tucking Behavior Not Just for Birds

Modern birds perform tucking movements to align themselves optimally within the egg prior to hatching. If that movement fails—whether in the wild or in artificial hatcheries—hatchlings often do not survive. Until now, this behavior had been considered an avian innovation.

Reconstruction of a close-to-hatching oviraptorosaur dinosaur embryo, based on the new specimen “Baby Yingliang”. Credits: Lida Xing

Reconstruction of a close-to-hatching oviraptorosaur dinosaur embryo, based on the new specimen “Baby Yingliang”. Credits: Lida Xing

The posture seen in Baby Yingliang challenges that assumption. This is the first evidence that non-avian dinosaurs may have practiced this same neural-muscular movement, extending the origin of pre-hatching coordination far deeper into evolutionary history.

The oviraptorosaur group, which thrived in the Late Cretaceous period, shares several physical traits with birds, including feathers, beak-like jaws, and brooding behavior. These findings reinforce a growing body of fossil evidence suggesting that the biological and behavioral foundations of birds were already well established in certain dinosaurs.

Fossils Offer Rare Glimpse Into Dinosaur Embryology

Dinosaur embryos are extraordinarily rare, and those preserved with fine skeletal detail and intact postures are even rarer. The preservation quality of Baby Yingliang suggests the egg was rapidly buried—possibly by a landslide or flood—shortly after it was laid. Such conditions would have protected the fossil from erosion and decomposition, locking it in a snapshot of Late Cretaceous life.

The Ganzhou region in Jiangxi Province, where the fossil likely originated, has yielded an unusually large number of well-preserved oviraptorid fossils, including nests and eggs. Yet until now, none had shown an embryo in such a clearly defined, behaviorally significant position.

In-ovo late-stage embryos of non-avian and avian dinosaurs. Credits: Cell/Xing et al., 2021

In-ovo late-stage embryos of non-avian and avian dinosaurs. Credits: Cell/Xing et al., 2021

Scientists involved in the study cautioned that while the evidence is compelling, this remains a single specimen. To fully confirm whether tucking behavior was widespread among theropods, more fossils in similar conditions will need to be studied using high-resolution imaging and computed tomography.

A Deeper Evolutionary Legacy

The posture preserved in Baby Yingliang doesn’t just reveal how some dinosaurs developed inside the egg—it pushes the evolutionary origins of bird-like behavior further back than previously known. If future finds confirm similar patterns in other species, it could prompt a re-evaluation of how much of modern bird biology is inherited from deep time.

This discovery also underscores how little we still know about the developmental biology of dinosaurs. While feathers, hollow bones, and brooding behavior have long been linked to dinosaur-bird evolution, the realization that deeply programmed behaviors like tucking may also be inherited opens a new dimension to evolutionary research.

The find strengthens the link between birds and dinosaurs—not just through bones or feathers, but through instinct. That subtle curl inside the egg, replicated over millions of years, might be the evolutionary whisper connecting the ancient oviraptor to the modern sparrow.