Read: 3 min

The Carney government’s 2025 budget promises security and prosperity. But just days after its release, two of Canada’s largest mental-health organizations warned Ottawa is undermining its economic goals by underinvesting in mental health and addictions care.

“If you want a robust, nimble, innovative workforce, you need to make sure that they are collectively mentally healthy,” said Glenn Brimacombe, director of policy and public affairs at the Canadian Psychological Association.

“There is a net social benefit, not only to them … but in terms of what they bring as an active member to society.”

Experts said mental health is directly tied to workplace productivity and national prosperity.

“[When] mental illness affects perhaps a fifth of the population in any year … it becomes clear that mental health outcomes can have important consequences for both individual and national productivity and prosperity,” Nadeem Esmail, director of health policy at the Fraser Institute think tank, said in an email.

Patchworks and persistent gaps

In Canada, the federal government funds mental health and addiction services provided by psychiatrists and primary care providers, within hospitals, and some detox and residential programs.

But public coverage for psychologists, counselors and ongoing therapy is limited.

The Canadian Mental Health Association has criticized this funding approach, noting it creates a patchwork of care across the country.

“In the Canada Health Act, there is no requirement … to provide universal access to mental health and substance use services outside of hospitals and doctors’ offices,” a spokesperson told Canadian Affairs in an email.

“Provinces and territories make their own decisions about which services they will publicly fund and to what extent they will fund them.”

Canadian Affairs has previously reported that many provinces have not allocated sufficient funding for addiction and mental health care services.

The Canada Strong budget, released Nov. 4, includes measures to fast-track the recognition of internationally trained health-care providers, invest in health care infrastructure through a new Health Infrastructure Fund, and enhance youth mental health counseling.

However, it confirms that 2017 funding for home care and mental health will expire in 2027 and allocates no new funding for pharmacare.

The Canadian Mental Health Association says the expiry of federal agreements will create a $600-million shortfall in 2027-28 for mental health and addictions services delivered outside hospitals and doctors’ offices, including counselling, psychotherapy and addictions programs.

Brimacombe, of the Canadian Psychological Association, says a failure to adequately fund mental health and addiction care will ultimately cost the system more in the long run.

“The growing number of Canadians with issues of anxiety and depression … has health, social and economic implications to Canada — or to any country, quite frankly.”

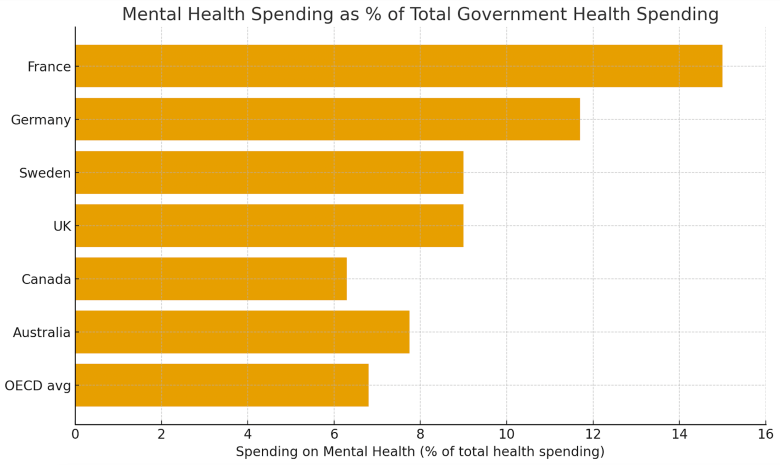

Canadians are reporting poor mental health at three times the rate seen before the pandemic. Canada also underinvests in mental health relative to other G7 countries. Nationwide, just over six per cent of health budgets are directed to mental health, compared with 9.5 to 15 per cent in other G7 countries.

Data source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), A New Benchmark for Mental Health Systems: Tackling the Social and Economic Costs of Mental Ill-Health; The Kings Fund, Mental Health 360: Funding and Costs.

Data source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), A New Benchmark for Mental Health Systems: Tackling the Social and Economic Costs of Mental Ill-Health; The Kings Fund, Mental Health 360: Funding and Costs.

Brimacombe calls spending on mental health an investment, not a cost.

“Canada’s future wealth includes investing in mental health. It’s a Gordian knot,” he said.

Work smarter, not harder

The Canadian Psychological Association is urging Ottawa to enact a Mental Health and Substance Use Health Care for All Parity Act. This act would be a companion to the Canada Health Act, making mental health and addictions services universally publicly funded.

Others say legislation alone is not enough.

“While many mental illnesses can be treated effectively, the vital issue for Canada’s health care systems is ensuring patients have access to these treatments and the practitioners that deliver them,” Esmail, from the Fraser Institute, said in an email.

Canada ranks 16th out of 28 developed countries with universal health-care systems for psychiatrists per person and 22nd for psychiatric care beds. Wait times for psychiatric care after a referral average more than six months.

Both Esmail and Brimacombe said better data and performance measurement are essential.

“Most of mental health is delivered in the community or outside of a hospital,” said Brimacombe. “We need better mental health performance indicators to tell us how the system is performing.”

Esmail noted some provinces are making better use of existing resources.

In Newfoundland and Labrador, for example, the provincial health authority has adopted a stepped-care model. Patients begin at the lowest appropriate level — self-guided tools or virtual supports — and move up to group therapy, counselling, psychiatry or hospital care as needed. The goal is to reduce bottlenecks and reach more people more quickly.

“Making better use of limited resources, with a focus on improving the availability of services over time, is essential,” said Esmail.

Related Posts