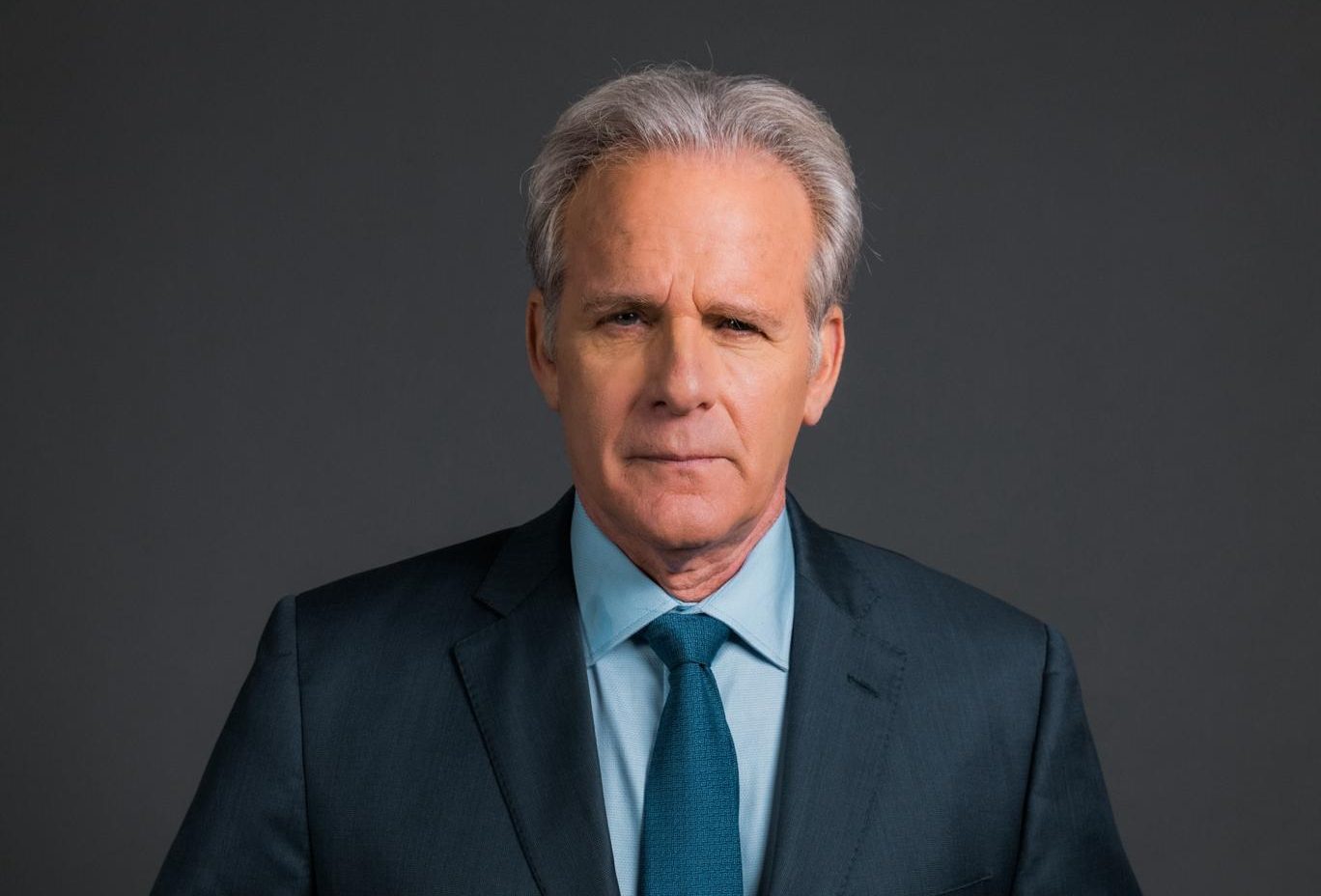

Former Israeli Ambassador Michael Oren, a diplomat, historian, and former member of the Israeli Knesset, says he has always refused to do public “gladitorial” debates when it comes to representing Israel these last two decades in public life. But the American-born statesman and author changed his longstanding practice to come to Canada this Wednesday, Dec. 3, to headline the Munk Debates onstage in Toronto. Organizers are mounting what they admit is their thorniest topic ever: be it resolved that supporting the two-state solution is in Israel’s best interest.

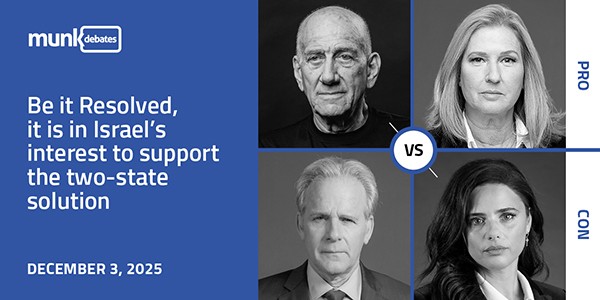

Oren is on the “no” side, together with former right-wing Israeli politician Ayelet Shaked. They’ll take on a former Israeli prime minister, Ehut Olmert, and former cabinet minister Tzipi Livni, who will be arguing for the “yes” side.

The debate is already attracting controversy for several reasons. There were no Palestinian voices invited on the program, and organizers are expecting protests, so security has been ramped up. They also had to move from their traditional venue, Roy Thomson Hall, for the first time in 15 years. But despite the sideshow, Oren believes the Munk Debates are important to reach a massive online audience with reasoned arguments, including why most Israelis oppose the two-state solution in any near future. He calls the proposal “deranged”, especially after Oct. 7, even though most Western countries, including Canada, are doubling down on the idea.

So what’s in store for Israel, Palestinians, and the Middle East? Oren joins The CJN’s North Star podcast host Ellin Bessner on today’s episode to share his take.

From clockwise from top left: the debaters include Ehud Olmert, former Israeli prime minister, and Tzipi Livni, former peace negotiator and cabinet minister, for the “yes” side vs. Ayelet Shaked, former right of centre cabinet minister, and former ambassador Michael Oren. (Submitted photo)

From clockwise from top left: the debaters include Ehud Olmert, former Israeli prime minister, and Tzipi Livni, former peace negotiator and cabinet minister, for the “yes” side vs. Ayelet Shaked, former right of centre cabinet minister, and former ambassador Michael Oren. (Submitted photo)

Related Links:

Learn more about watching the Munk debate on Dec. 3, 2025.Follow Amb. Michael Oren’s columns, his Israel 2048 organization and his books, at his website.Read Amb. Michael Oren’s praise for former Canadian prime minister, Stephen Harper and foreign minister, John Baird, during a 2013 speech in Montreal, from The CJN archives

Host and writer: Ellin Bessner (@ebessner)Production team: Zachary Kauffman (senior producer), Andrea Varsany (producer), Michael Fraiman (executive producer)Music: Bret Higgins

Support our show

Transcript:

Douglas Murray: Today, the only really acceptable form of anti-Semitism, aside from the sewers of the far right, the only real tolerated form of anti-Semitism is anti-Zionism.

Ellin Bessner: That’s some of what it sounded like last year at a high-profile Munk Debate in Toronto. That topic was whether anti-Zionism equals antisemitism. You might have heard about this particular event, maybe you even watched some of the videos later on YouTube. The “yes” side featured Douglas Murray, the British journalist whose voice you heard off the top, with his debating partner, British lawyer Natasha Hausdorff, going up against journalists Mehdi Hassan and Gideon Levy.

According to the Munk rules, the audience voted at the beginning and the end of the night, and the pro-Israel side won.

Now, scoring a debate victory in a Toronto theatre eight months after October 7th may have been on the debaters’ personal bucket list, but it likely wasn’t the main reason they agreed to come to Canada and do that Munk gig. Instead, it’s probably because their arguments were amplified way beyond Toronto and spread to a massive online audience: tens of thousands of views on YouTube, countless news articles and social media posts.

And that’s why Michael Oren, Israel’s former ambassador to the United States and a former Knesset member says he agreed to come to Canada this Wednesday from Israel to be part of possibly the most controversial Munk debate which the organization has ever staged, having 4 Israeli former politicians to debate this: “Be it resolved that supporting a two-state solution is in Israel’s best interests.”

The Munk debates were put together 15 years ago after a grant from a Holocaust survivor and former mining magnate, Peter Munk. Oren will be on the “no” side. His partner is right-wing former Israeli cabinet minister Ayelet Shaked, and on the “yes” side, they’ll face former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert and Tzipi Livni, a former peace negotiator. The others weren’t available for interviews before the debate, but Ambassador Oren was.

He knows them all, and he says he expects none of what will be said is new, except that they haven’t had this debate before inside Israel. But he wants to explain to the world why, after October 7th, the majority of Israelis feel accepting a Palestinian state is, in his words, “delusional” and “absolute insanity”, and why he feels it poses an existential threat to Israel and also why Canada and many Western countries’ recognition of a Palestinian state in September has actually backfired for the Palestinian people. The fighting has not ended despite the current Trump-brokered ceasefire in October.

Michael Oren: The blood is on the hands of these governments that stiffened Hamas’s resolve at the negotiating table because they realized they got a tailwind. They got a tailwind from Paris, from London, and from Ottawa.

Ellin Bessner: I’m Ellin Bessner, and this is what Jewish Canada sounds like for Monday, December 1st, 2025. Welcome to North Star, the flagship news podcast of The CJN, made possible thanks to the generous support of the Ira Gluskin and Maxine Granovsky Gluskin Charitable Foundation.

Michael Oren made Aliyah to Israel in the 1970s, served in the IDF. He has degrees from Princeton and Columbia. He became Israel’s ambassador to the United States in 2009 under the Obama administration. Then he was a member of the Knesset and worked in Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s office until 2019. He’s a popular author and pro-Israel columnist, and podcaster. He’s now writing a book about the circumstances surrounding the October 7th war, and he runs a new organization called Israel 2048 to create conversations about what Israel should look like on its 100th birthday.

For a preview of his arguments and a general discussion of peace prospects, Iran, Prime Minister Netanyahu’s future and possible pardon, and more, I’m joined now by the former ambassador. He was in New Jersey while he was spending the American Thanksgiving holiday period with relatives. It’s an honour to meet you.

Michael Oren: Ellin, the honour is mutual. The pleasure is mutual. Delighted to be with you.

Ellin Bessner: I would love to know why did you agree to participate?

Michael Oren: Actually I get that question about 4 times a day, by the way. So here it is. Here’s the simple answer, the peshot, as we say, in Judaism, the peshot is this: I’ve been invited to appear in many debates over the years, and I always turn it down. I find them gladiatorial. I don’t like fighting somebody on a stage for other people’s enjoyment. But this debate is qualitatively different, and it is on a subject which is of immense importance to Israel right now. It is a highly, highly topical and widely, widely misunderstood.

So, you have many governments in the world, most recently the Canadian government, recognizing a Palestinian state unilaterally. And the sort of knee-jerk, let’s say, liberal response was, “Well, why not? You know, why not have a Solomonic solution to this horrible conflict? Just divide the land and call it a day. Let’s have a Palestinian state live side by side with peace and prosperity, with the Jewish state.” And that is the reaction of many people, and I can understand that reaction. And yet the vast majority of Israelis reject that position. And explaining to the world why we reject that position, why we view the creation of a Palestinian state as not bringing peace, but bringing war. And bringing a fundamental and potentially existential threat to our state, to our communities, to our families is of utmost importance right now.

And so, I agreed to do the debate to get this message across, to speak to a large audience, and the Munk debates have a multiplier effect cause it’s not only speaking to the audience in the hall, but it’s on YouTube, it goes through social media. To explain to an incredulous world why Israel would turn down this seemingly innocuous and simple Solomonic solution of dividing the land between Palestinians and Israel, as if it hasn’t been tried. And tried repeatedly for close to 90 years, and every time with the exact same result.

Ellin Bessner: You mentioned that the audience is not just in the hall; in fact, the organizers said that their actual audience is 7000 kilometres away, back in Israel, and this is a debate they feel could not yet happen in Israel, but they want it to. What do you make of that framing?

Michael Oren: Difficult. It’s true that Israelis are not willing to hear about a two-state solution, certainly not at this time. I can speak for my own family, which I’d say is centre, centre-left family. For them, the notion of a two-day solution is absolute insanity, insanity after October 7th. At a time when the majority of the Palestinians still support Hamas, still celebrate October 7th, you should know. And I don’t know what the case that Tzipi Livni and Ehud Olmert are going to make, whatever case they make, it was one that’s not going to speak to a great number of majority of Israelis right now. We’ve heard it all before, there’s nothing new about it. Yeah,”If we don’t make two states, we’re not going to have a democratic and Jewish state.

We’ll be isolated in the world.” These, these are not new arguments.

And I’m not a debater. I haven’t debated since high school. But I will do this in order to get this message across. And, you know, they do a vote before and after, Ellin. I don’t know whether we can win that vote, and it’d be nice to win the vote, but that’s not the major objective here. But I think in addition to trying to convince people who may think otherwise, I think we’re providing important information for those who go out and defend Israel and may not have the tools, and I view ourselves as giving those tools and providing maybe some facts that people don’t know. I mean, how many people know that the Palestinians hold the world record for

people who’s been offered a state, been offered a two-state solution, has turned it down and not only turned it down, but turned it down with mass violence?

It’s quite extraordinary. How many people today know that 2/3 of the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza oppose the two-state solution? How many people know that if Hamas were to run for office today, it would still win and that the majority of Palestinians still celebrate October 7th? That these are facts that are not well known, not even to Israeli supporters in the world. So our job, something that Ayelet, and my job is, to provide tools to build a case for Israel.

Ellin Bessner: Look, there has been criticism here in Toronto and around the Munk Debate because it has 4 Israelis debating and there are no Palestinian voices. You aware of that criticism at all? Have you heard this?

Michael Oren: No, I anticipated it, not surprising in the least, but I think the thing to remember, this is an internal Israeli debate. It’s not, you know, the Palestinian voice, you know? That’s another different, that’s a different debate, and we can have conversations about other aspects of Israeli governance that divide the Israeli body politic. Most recently now, the question of ultra-Orthodox service in the military, the question of whether there should be a state or a political commission to investigate the failures of October 7th. The judicial reform program.

The two-state solution, I must tell you honestly, is one of the lesser issues that divide Israelis because most Israelis, as I said before, opposed the creation of a Palestinian state.

Ellin Bessner: Earlier, you mentioned Canada’s unilateral recognition in early September. What do you make of why Canada’s taking this position together with, you know, the UK and the EU? When Canada called for de-escalation of Israel’s fight with Iran in the summer, you called it a “perverse moral universe”, right? OK.

Michael Oren: Oh, there we go, “perverse moral universe”. Well it is a perverse moral of the universe!

I can’t speak for your Prime Minister, for your government. There’s certainly a domestic political aspect to it. There’s an ideological aspect to it. I would have liked to have seen Canada adopt a more independent position from its previous colonial masters and not seem like it’s, you know, emulating the French and the British.

Canada put down all these conditions and then didn’t live up to the conditions. They didn’t even wait for the conditions, I mean, really. It’s diplomacy as comedy. It’s diplomacy as parody. It’s diplomacy as farce. There is no Palestinian state. The Palestinian state does not fulfill any of the requirements of a Weberian sovereign state. And all that does, by the way, is to stiffen Hamas’s position at the negotiating table. That’s all, that’s all it accomplished. Basically, Canada’s position cost Palestinian dead.

Ellin Bessener: One of the things that you’re going to obviously talk about is the damage in international relations that Israel’s war has cost in terms of, well, you just mentioned a few of these capitals that have already turned their backs on Israel. Can we talk a bit about why you think it’s so important? While the ceasefire is shaky, and while things are, you know, working out in the short term in terms of Israel, Gaza and the Middle East, what Israel needs to do to establish or reestablish better relations with some countries, such as Argentina, why that’s so crucial?

Michael Oren: Well, let’s take a broad view, a historical view, OK. I’ve been living in Israel for a long time. You hear from my accent, I wasn’t born there, born actually, not far from the Canadian border, upstate New York. The Israel I came to, (and I’ll age myself by saying this is the sort of mid-70s), was a country that had no relations with China, no relations with India, no relations with the 12 states that were members of the Soviet bloc, Eastern European states, the Central Asian states. No relations with African countries. They’d all cut off relations with us after the Arab oil boycott of 1974, very few relations with South America. A friendly relationship with

the United States, but not a strategic alliance with the United States. No peace with Egypt, no peace with Jordan, certainly no peace with the four signatory nations of the Abraham Accords. Do not tell me that Israel is more isolated today than it’s ever been, because historically that’s simply false.

And in fact, I can make a case that even today, after this war, Israel is significantly less isolated than it was throughout the 1970s, 1980s, you know, into parts of the 1990s. And it was during my period in government, when I was the deputy for diplomacy in the Prime Minister’s office, we had the African countries literally standing in line to renew relations with us. This is not ancient history.

And so today, yes, we have strained relations. We have strained relations, say with France, with Britain, with several European countries. Well, Belgium and Luxembourg and Canada and the Democratic Party, it has to be said, in the United States of America. That is all true, and you cannot, I will not, you know, in any way diminish the seriousness of this, particularly with the Democrats.

Because, in Europe, governments can change. We’ve seen them change. I think there’s going to be a change in the government in Britain. There could be changes in the government in France. They may have a very different policy toward us. We’ve seen what’s happened in South America with Argentina. Let’s see what happens now with the changes of governments that are pending in Bolivia and Chile. I think the Colombian government will change, so governments can come and go and change.

The Democratic Party is a different issue. It’s very deep-seated there.

And Israel has to do its utmost to reach out and try to rebuild these, these relationships to the degree that we can, because so much of the criticism of Israel now in the West, it’s not so much in the East, it’s not about what we do, but what we are. We can create a Palestinian state tomorrow, and you’re still going to, the people are out chanting, you know, for a globalized intifada, and “we don’t want no two states, we want 48.” They’re not about the two-state solution. They’re about destroying the State of Israel. So we have to be aware of that. There’s a degree to which we’re going to be able to change that and be humble about it.

Having said all that, Ellin, even today, in the aftermath of this war, the chances of the Abraham Accords expanding and just recently expanded with Kazakhstan are very great, and we can see peace with Israel in Lebanon, peace with Israel in Syria, certainly peace with Israel and Saudi Arabia. Through Saudi Arabia, it’s not just peace with Saudi Arabia, it’s peace with the entire Sunni world, it’s Indonesia, Pakistan. I, with all due respect to our dear friends in Canada, I would rather have all of that than renewed friendly relations with Canada.

And I think that one of the reasons that these countries are seeking closer relations with us is because we’re strong, because we have stood up to their enemies as well. Their enemies are also Islamic extremism, you know, there are countries and certainly areas of the world that respect that strength, and certainly we’ve earned it. Among certainly liberal circles in the West, there’s a recoiling from military matters and understanding what it means to win against an enemy that seeks your destruction, seeks the destruction of your civilization and how complex war is. But in our area of the world, that doesn’t exist. They understand, they understand very well. So I think we’re going to rebound to a very large extent if the ceasefire holds. And I think we’ll actually expand our circle of peace, not detract it.

Having said all that, one last thought. We do have to have a policy about the Palestinians. It’s not the two-state solution. And one of the key points I’ll be making on the Munk stage is that the two-state solution is a tragedy first and foremost for the Palestinians. Beause it’s not going to happen and what it means is you can never advance with other creative ideas. And there are other ways we can provide what they know as a diplomatic horizon for the Palestinians. We can do that.

We can expand the autonomous semi-independent state that

already exists in Judea and Samaria, the West Bank. We can do many things. We can’t do it if the world keeps banging its head. Look at how the West keeps banging its head on the two- state formula. And I talked to people, I talked to people in liberal circles in the United States and elsewhere, and they said, ”Listen, we know this, we know that it’s not going to happen. But we have no choice, you know, that’s our ideology, that’s our platform.” And that first and foremost is a tragedy for the Palestinian people.

Canada’s recognition of the Palestinian state had almost nothing to do with the Palestinians. It had everything to do with Canada.

Ellin Bessner: Look, you mentioned some sort of smaller ways in order to have maybe, and I’ll use some of the words you’ve used, cantons or condominiums or a different kind of smaller regional Palestinian path to statehood. Can you show a little bit of what that would look like for our listeners who may not have heard this third way?

Michael Oren: So there are 3rd WAYS, not way. The 3rd ways. Some years ago I published an article in the Wall Street Journal called the two-state situation, the two-state reality, you know.

You get into a car in Israel, you drive up Highway 6, that’s the highway that goes up what used to be the ’67 border going north, you look to your right, you see big Palestinian cities like Qalqilya and Tulkarm, and over those cities fly huge Palestinian flags. In those cities, there’s a Palestinian government, there’s a Palestinian police force. There is already an embryonic state there. It is not a fully sovereign state. (And really can’t be because if that state can’t have an army) and it can’t make a military pact with Iran. But we can expand that autonomy, we can expand it juridically, we can expand it even physically. And we can make it more stable, we can invest in development there. So that’s very low-hanging fruit. Countries that say, ‘Oh, we can’t do that because we want a two-state solution,’ are harming the Palestinians.

There is another idea that has been around for several years, and I’m rather partial to it, and that is a Swiss model cantonization program where you have cantons, say in Hebron, cantons in Nablus that are family-based, based on the local clans, not based on national corrupt movements like Al-Fatah and the PLO or jihadist movements like Hamas. And their interests are in developing Hebron and developing Nablus. And we can live, I think, side by side with these cantons, we could be federated with these federated, we’d be in relationships with them.

Now, the original two-state formula, one of the original two-state forms of the UN from 1947, was for an economic federation between the Jewish state and the Arab state. It wasn’t a Palestinian state back then; it was an Arab state. So these ideas are not new, and we can explore them; we can be creative. But you can’t be creative if you’re taking the same formula over and over and over again that has failed consistently for 90 years.

Ellin Bessner: Many Israeli commentators have called what the relationship is now as Bibi- sitting, if our listeners have not heard this. Basically, the bear hug that the American leader has now put on Netanyahu, that Israel has lost some of its sovereignty. Are you on that page as well? And how do you see what the sort of client relationship is now with Israel and Trump?

Michael Oren: I’m on the page. I’m on the page Ellin, but in a nuanced way.

Again, I have to wear that historian’s hat. Israel, you know, we gained our independence in 1948, but very quickly it was, it was clear that we were not going to be completely sovereign, that we’re going to be highly dependent on the West and later on the United States. And beginning with our second war, the Sinai War of 1956 to ’57, for which (the late Canadian prime minister) Mike Pearson got the Nobel Prize, the United States told us to stop, and we stopped.

The Six Day War would have been an eight day war, you know, I personally had to bring American fiat to Israeli leaders saying, “Guess what, you want the war to go on, but we’ve got to stop tonight and we’ve got to stop at 8 o’clock tonight.” And Israeli leaders weren’t thrilled about it, but we stopped, each time we stopped.

Now, it’s very rare, with rare exceptions, you know: the operation against the Iraqi nuclear reactor in 1981 or against the Syrian nuclear reactor in 2007, we operated, you know, not with the coordination or even the knowledge of the United States, but it’s very rare. So there’s nothing new about Donald Trump telling us to stop in Iran. Or Donald Trump telling us to stop in Gaza.

What is different today? We have two major differences. One is that for the first time in our history, we have a foreign military force, known as the CMCC, the Civilian Military Coordination Center in Kiryat Gat, 200 American soldiers, but also soldiers from around the world, France-

Ellin Bessner: And Canada’s got somebody there.

Michael Oren: -and Canada, and Spain, for some crazy reason, they’re all there. The first time we’ve had a foreign military force on our soil monitoring our military and limiting our military. That is a major price to pay in terms of our sovereignty. For the first time in our history, we have virtually no recourse.

So, you know, historically, whenever we had a problem with the president, we’d go to the opposing party and complain. And there’s no one to complain to today. If you have problems with any of Donald Trump’s policies, you’re not going to go complain to the Democrats about it. So that puts us in a uniquely vulnerable position and a uniquely dependent position. And this is a particularly strong president. You know, President Biden, and I have a great regard for him, I worked with him and his staff. He said, ‘Don’t.’ He famously said ‘Don’t’ at the beginning of the war, and everybody did. Israel did. The Palestinians did. The Iranians did. Everybody did. Donald Trump says ‘Don’t,’ and people don’t dare.

Ellin Bessner: So how serious is this for Israel’s control, responsibility, as you like to use the word, over what goes on in its borders?

Michael Oren: Well, we always have a choice, but the choice comes with a price. For example, we have different interpretations of how to define a violation of the ceasefire in Gaza. A couple of weeks ago, we had 2 soldiers killed, 2 beautiful soldiers killed. For us, that’s a national tragedy, and Israeli public opinion expects a very strong response. From the White House was, ‘Oh, you know, there was an incident, but this ceasefire is basically holding.’ And so we have different interpretations. So at a point we may have to say to you, even to this president, you know, “As much as we respect you and appreciate your support, we’re going to have to act in a sovereign way” and I hope that, I hope that’s the case. Listen, I hope that, I think that I hope the Command Centre succeeds in its mission, which is not to limit Israel’s military response, but to rebuild Gaza as a friendly area.

Front page of The New York Times today talks about creating communities, prefab communities-

Ellin Bessner: On the Israeli-held side.

Michael Oren: …on the Israeli side. And on paper, it looks very good. Certainly, if it’s, you know, if you’re sitting in Saskatchewan it’s a good program. In the Middle East, it may not be. First of all, the question is, OK, who’s going to live there? Who’s going to voluntarily live under Israeli occupation?

You could have a situation that anybody who agrees to live in one of those prefabs will get a bullet in his head from Hamas, which is very, very likely.

And even if they do move into these communities, you can pretty much count on your watch, the time it’s going to take before the first Hamas crew comes out of there and attacks because you’re not really changing, because in the West, there’s this notion which we find very peculiar in Israel that Hamas landed in Gaza from Mars and was somehow not a product of Palestinian society. So you’re taking the same society, putting it in new houses, it’s not going to get rid of Hamas. You’re not de-radicalizing. You’re not, you know, what we would call back in the day de-Nazification. You’re not. And so you’re simply taking a society which produces Hamas and putting it in a couple of new houses. And then expecting that Hamas is not going to come out of those new houses.

Ellin Bessner: Back to the relationship with the two leaders, Netanyahu and Trump. There’s an election coming up in a year from now. Should Netanyahu be sent back to office? Is he the one that should stay at the helm during this whole reconstruction and the next steps, phase 2, phase 3, whatever it is, or is it time for him to go?

Michael Oren: Well, it’s not for me to decide. It’s always premature to eulogize Mr. Netanyahu politically. He’s the ultimate comeback kid, and I happen to live in an area of South Tel Aviv, Jaffa, where he is very popular. You don’t say a word against Benjamin Netanyahu in my neighbourhood, and he will always have a solid base. And in our multi-party system, that solid base can translate into tremendous political leverage. So I wouldn’t rule out the possibility that he’s going to run again, and I wouldn’t rule out the possibility that he will do very well in those elections.

Ellin Bessner: But Trump wants him pardoned, too. Would that help? Is that helping?

Michael Oren: Well, a pardon would certainly help, but under Israeli law, if you get a pardon, you have to admit guilt. I don’t think he’s going to do that. I don’t know.

I think there are ways out of this logjam, but it requires a sort of a modicum of goodwill on the part of the parties involved, including the justice system.

Having said all that, I write a weekly column in Hebrew for our major newspaper, Yedioth, and my column this week, it came out two days ago. I came out and called for a state-independent inquiry into the events of October 7th, which Netanyahu’s government robustly object to, but I take his argument seriously. His argument says that you can’t have an independent commission that’s staffed by Supreme Court judges who have been at war with me for years now. Can’t expect that to be objective.

I said, OK. Let’s have a state commission that’s not made up of Supreme Court judges. Israel is blessed with a great number of public figures who are morally, you know, supreme people who are smart and very, you know, what we call bipartisan or multi-partisan, and you could easily put together, I think a panel that would be naturally respected because I fear that the division in Israeli society over this inquiry or the lack of one, will be deeper than what we’ve experienced both with the controversy over the judiciary reform and the issue of a ceasefire.

Ellin Bessner: Many countries have gone through this, including Canada, (Truth and Reconciliation Commission). South Africa’s had them. Other countries after the Holocaust too, many years later, in order to heal and to be resilient and to move forward, and prepare for the next war, as you said. How long can Israel continue to still be full of turmoil and angst, waiting for the bodies, waiting for the next shoe to drop, and what would this commission do? Would this do the trick to heal them?

Michael Oren: It’s not a healing commission. It’s not about that. It’s a different commission.

Ellin Bessner: It’s an accountability commission more?

Michael Oren: And accountability is an essential part of our resilience. If we haven’t learned that very essential lesson about October 7th, Hamas taught it to us. We know from the documents that we’ve captured in Gaza, Hamas did what it did on October 7th in large measure because we were divided. And divisions within Israeli society- we can have, certainly, differences of opinion, you’re going to hear about them on the stage of the Munk debates. We can have those divisions, but we have to understand that at a certain point, those divisions become a strategic liability and a danger.

Ellin Bessner: How does he survive this, even without a commission for now?

Michael Oren: Well, you know, historically accurate, Golda Meir just lost the election afterwards. She was actually exonerated by the Agranat Commission. That placed the bulk of the blame for the Yom Kippur War surprise on October 6th, 1973, on the military and not on the political echelon. This is precisely what Netanyahu is claiming: that the responsibility doesn’t fall on him and his government, but on the military, which led him to believe that Hamas was not interested in war. Hamas was interested in, you know, Gaza development.

The reason that the issue is going to be so divisive because it pits the government against the military. And not just against the military, against the entire security apparatus, it’s the Shin Bet, it’s the Mossad. But more deeply, it cuts across right and left.

There are going to be two issues in Israeli politics coming up. One of them is Haredi service in the military. The other issue will be the state commission of inquiry. Why? Because on October 7th and afterwards, altogether something more than 2000 Israelis have been killed, tens of thousands have been wounded and terrorized. Hamas didn’t distinguish between left and right. So it’s going to cut very deeply across right and left, and the only way I think to avert that type of division, which will be again strategically dangerous for us, is to appoint a state commission of people who are greatly admired in Israel, who have standing in our society and are not members of the Supreme Court.

Ellin Bessner: Sharansky, people like that?

Michael Oren: I mentioned Elliot Key Rubenstein. I mentioned Mika Goodman from the Hartman Institute, a couple of philosophers, a couple of military people I mentioned who would be very good or not identify with right and left.

Ellin Bessner: Would you say yes if they asked you?

Michael Oren: Definitely, but I don’t want to put myself in this category.

Ellin Bessner: Now you’re writing a book about October 7th-

Michael Oren: No, can I stop you? Excuse me for interrupting, but there as of today about 700 books about October 7th. Every week there’s a new one, and they are heart-wrenching beyond belief. But there’s no book yet about this war. And this is the longest war in Israel’s history. It is potentially the most transformative war in Israel’s history, even more than 1967. It is an immensely complex war. No one has written that book. I’m aspiring to write that book.

Ellin Bessner: So the military history, taking apart the battles, the strategy, the challenges, the tunnels.

Michael Oren: That’s just part of it. It’s what’s going on in the White House? What’s going on in the Knesset? What’s going on the streets of campuses in North America? What’s happening in the UN? What is happening in Gaza? What is happening in Lebanon? What is happening in the militias in Syria and Iraq? What is happening with the Houthis? What is happening in Judea and Samaria, and what is happening with Iran? So, can you imagine the mass of this?

Now, the great challenge for me is, you know, in the past, you write a book about ’67, you can sit in an archive and look at cables. The source material for a book like this is Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp messages. It is potentially limitless, and to get an understanding of exactly what happened, why it happened, who are the decision makers…is the greatest academic challenge I’ve ever faced.

It’s also an immensely emotional challenge.

Ellin Bessner: I hear you. Thank you very much for joining us on The Canadian Jewish News.

Michael Oren: All right, take care.

Ellin Bessner: And that’s what Jewish Canada sounds like for this episode of North Star, made possible thanks to the Ira Gluskin and Maxine Granovsky Gluskin Charitable Foundation. To catch the live stream of the Munk debate, you can go to the link in our show notes. I’ll be there in the audience.

North Star is produced by Andrea Varsany and Zachary Judah Kauffman, with Michael Fraiman as the executive producer. The theme music was by Bret Higgins, and thanks for listening.