It’s late summer and UM researcher David Babb is sharing his packing list for his 24th trip to the Arctic. He has the essentials: ski goggles for when the snow blows up, GPS in case he gets separated from the research ship, warm socks, boots, gloves—and lots of them.

“When you’re out on the ice,” explains Babb [BScPhG(Hons)/2010, MSc/2014, PhD/2024], in the living room of his Winnipeg home, “you’re a long way from a warm spot where you can dry off your gloves.”

While this sea ice scientist and alum has prepped for Canada’s remote North many times—this cruise is different. Historic, even.

It’s the first time Canada’s research icebreaker will sail the country’s northernmost waterways. Only now has melting sea ice from climate change opened these particular waters to explore by ship. And it couldn’t come soon enough for scientists wanting to survey a region that holds a lot of intrigue.

This area in the Canadian Archipelago is expected to be the last place on the planet to have sea ice intact. Scientists predict this final melting could happen as early as the coming decade.

A Research Associate with the University of Manitoba’s Centre for Earth Observation Science, David Babb packs up his gear within days of his excursion aboard the CCGS Amundsen research icebreaker // Photo by Katie Chalmers-Brooks

On Sept. 4, Babb embarked for four weeks aboard the CCGS Amundsen during this first-ever cruise of the Queen Elizabeth Islands and western Tuvaijuittuq. He says it’s crucial that science have a baseline. Only then can they effectively monitor the effects of a warming climate.

“Canada is in a bit of a unique situation because the last ice will be in Canadian waters. As a country, and as Canadian scientists, we have a responsibility to make sure we understand this area and are able to guide any future mitigation efforts in this region—what we could do to try to help stabilize this environment in the future,” says Babb, who was a Chief Scientist on the ship.

UM’s David Babb and Lisa Matthes, from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, gather in the ship’s bridge to discuss planning as Co-Chief Scientists // Photo courtesy Amundsen Science

There’s been very few observations from this area throughout history.

Babb calls this area “dramatically understudied” compared to other parts of the Canadian Arctic. To date, there’s been a long-serving weather station there, which does hourly readings, but has allowed for only the occasional research sampling. This is the first time a full complement of Arctic experts—roughly 40 scientists—have surveyed the location from multiple angles, around the clock.

They headed north from Resolute Bay to Eureka Sound, up to Nansen Sound and Greely Fiord, and to the surrounding fjords, accessing the area that contains some of the oldest sea ice left in the Arctic. Wind and ocean currents push ice across the Arctic Ocean to this spot, creating a pile up, and the conditions to keep it frozen the longest.

The Amundsen, which doubles as Canada’s Coast Guard ship, becomes home base for scientists venturing onto the ice for sampling, or travelling via helicopter to survey nearby icebergs and ice islands // Photo courtesy Amundsen Science

Scientists create mathematical models to predict sea-ice melt but measurements taken in the field provide greater accuracy, Babb notes. Estimates differ on how soon this ice could disappear.

“Some peer-reviewed papers predict as early as the 2030s. Some predict by the middle of this century. This is one of the most contentious [topics] in the sea-ice community,” says Babb.

On this trek, the thickest ice they found was more than 7 metres. But it wasn’t in abundance.

“We had a very tough time finding older, thicker sea ice. Early on we thought maybe the ice in this area isn’t as thick as what we had expected, and maybe the warming had gone further than what we had expected,” says Babb, upon their return.

“There is still thick sea ice, but just not as much of it as we would have expected.”

A three-time UM alum, David Babb found his passion for Arctic sciences while still in high school, when he was invited aboard the Amundsen ship as part of the outreach program Schools on Board // Photo by Clement Soriot

Knowing what’s happening in this part of the Arctic—in the Tuvaijuittuq Marine Protected Area and southern areas of the Queen Elizabeth Islands—will also inform how to protect ice-dependent species like polar bears and seals, which are expected to migrate here for refuge as ice disappears elsewhere.

“Some people suggest that polar bears can adapt to a more terrestrial life. Other people don’t agree with that,” says Babb.

David Babb, in the bridge, planning the ship’s schedule // Photo by Clement Soriot

A better understanding of what’s happening to ice-cover will also inform shipping routes as the Arctic opens up to cargo transport, with longer ice-free stints every year, creating new pathways to Asia, Europe, Africa and the Americas. Just south of the region the Amundsen sailed is the Northwest Passage.

And even further South, on the shores of Hudson Bay, researchers at UM’s Churchill Marine Observatory (CMO) are working with the local community to monitor environmental impact amid new interest in Churchill’s port—Canada’s furthest north and only deep-water seaport reachable by train.

This November, researchers mimicked diesel spills in CMO’s pools, which pull in water from Hudson Bay. They want to know how the microbe community responds to the contaminant and detect it using satellite technology.

On the Amundsen, too, they tested satellite technology, to see how accurately it was reading characteristics of the ice they were seeing first hand.

“Of course, in the Arctic, we can’t always be there in person, so we rely a lot on satellites,” says Babb.

The Amundsen in front of the glacier at the end of Otto Fiord // Photo by Alexander Normandeau

“It’s about as far away as you can get from humanity.”

The team aboard the ship included a dozen UM members, along with scientists from other Canadian universities and agencies, and collaborators from Norway. UM researchers measured contaminants like mercury in the ice, and profiled the microbiology in the area. Members of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans looked at how the ice thickness affected its innate ability to absorb carbon emissions.

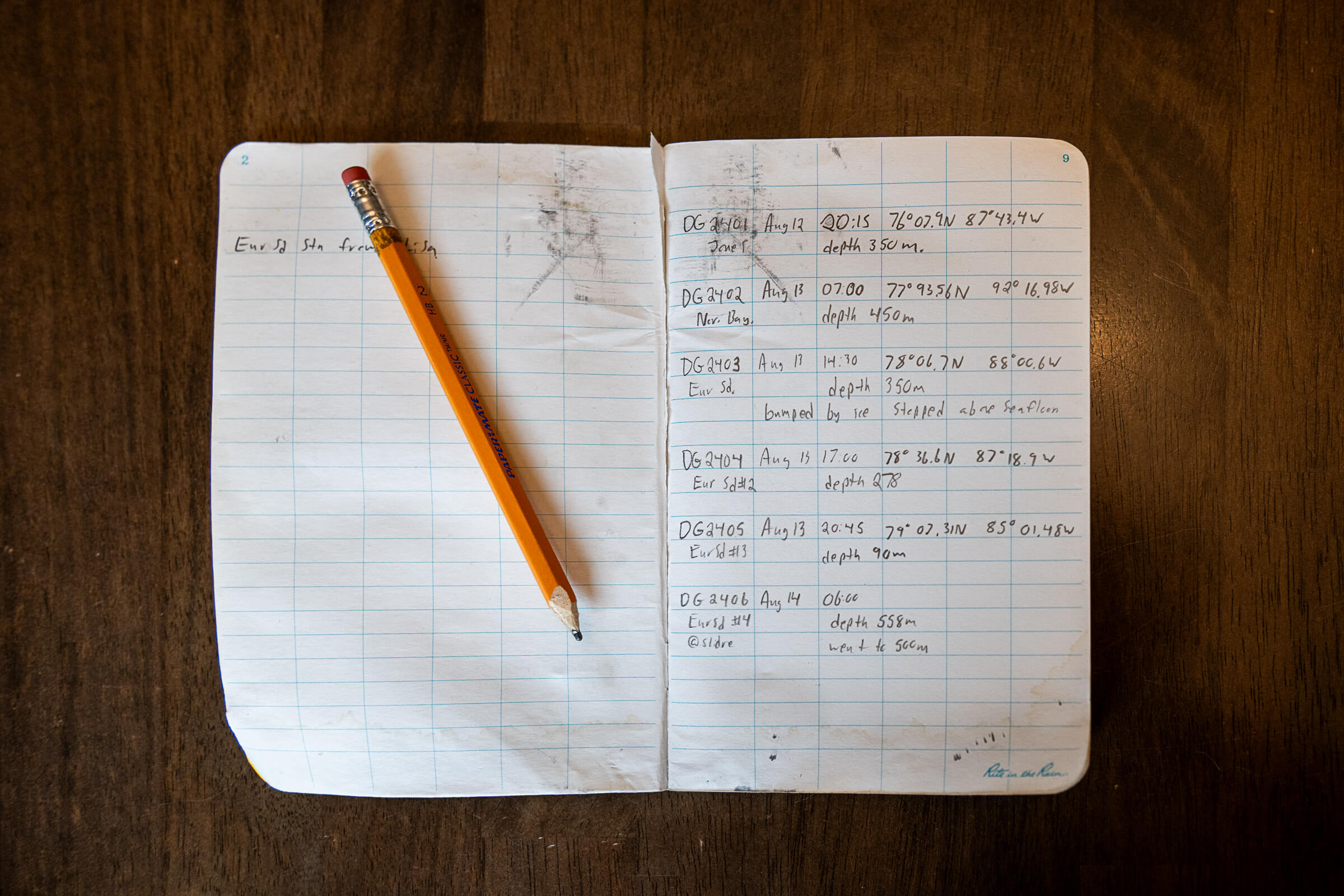

David Babb is never without his field book, where he tracks coordinates and observations // Photo by Katie Chalmers-Brooks

This fieldwork provided a snapshot for the scientists, but they also left behind moorings that they’ll recover data from a year from now, which will reveal a more fulsome story. And they deployed remote GPS beacons on the ice, about the size of a milk carton, to track how the ice drifts. These devices send coordinates hourly, showing how ice is moving south from the Canadian Arctic Archipelago towards the Northwest Passage.

While there wasn’t an abundance of thick sea ice, Babb says he was surprised by the quantity of thinner ice still intact that time of year.

“I was shocked at how much ice was still in the area during the end of summer,” says Babb. “It just reaffirmed that it’s not as open as we expect it to be. And there is still quite a bit of variability in the ice conditions along the Northwest Passage.”

This kind of knowledge will help inform design requirements of shipping vessels wanting to operate in these waters. The area, too, has additional challenges for a ship captain, given it’s largely unmapped, only a few hundred metres deep and home to frequent shoals.

Members of the ice sampling team get to work at sunrise // Photo by Clement Soriot

This first historic cruise, which wrapped up Oct. 2, is the start of a new and important conversation for Canada, says Babb. It was a long time coming and UM is at the forefront.

“The analysis and the work from a project like this will be in progress and published and analyzed for years to come—it’s an interesting first step. We’re just at the beginning.”

UM is home to scientists, students and scholars who respond to emerging issues and lead innovation in our province and around the world. Creating knowledge that matters is among the priorities you’ll find in MomentUM: Leading Change Together, the University of Manitoba’s 2024-2029 Strategic Plan.