Outside, the unassuming warehouse-like building is silent.

You’d drive by CAL-2, the largest operating data centre in the Calgary area, in an industrial park northeast of the city, without ever realizing it has 26 megawatts of power capacity to run what’s inside — enough electricity for roughly 26,000 homes.

In its depths, having passed through several hallways and doors, one of its data halls is buzzing loudly from the hum of computer servers that host cloud computing (online space that stores files and other data) for some of the world’s biggest tech companies.

Over the past year, as demand for artificial intelligence has soared with the evolution of generative AI, so has the federal government and Alberta’s interest in capitalizing on the AI boom by building data centres like CAL-2.

CAL-2 is eStruxture’s 26-megawatt, highly-secure facility in Rocky View County, which surrounds Calgary to the north. (eStruxture)

CAL-2 is eStruxture’s 26-megawatt, highly-secure facility in Rocky View County, which surrounds Calgary to the north. (eStruxture)

But there’s a disconnect between the province and industry’s ambitions, and ordinary Albertans who are hesitant to agree to data centres without understanding what they’re getting into, said Sabrina Perić, an associate professor in the department of anthropology and archaeology at the University of Calgary.

On the one hand, you have companies like eStruxture, the Montreal-based operator of CAL-2. Vice-president Taylor Hammond said the company has big ambitions to grow in Alberta. It’s already begun building CAL-3, a 90-megawatt AI data centre that will have more than three times the power capacity of CAL-2, also in Rocky View County.

“The Alberta market has a cool climate. It has access to power. It has access to … both tradespeople for construction as well as skilled data centre operators,” he said.

Taylor Hammond is vice-president and head of corporate development and capital markets at eStruxture, Canada’s largest data centre operator. Behind him, is a rendering of CAL-3, a 90-megawatt facility set to begin operations in 2026. (Rebecca Kelly/CBC)

Taylor Hammond is vice-president and head of corporate development and capital markets at eStruxture, Canada’s largest data centre operator. Behind him, is a rendering of CAL-3, a 90-megawatt facility set to begin operations in 2026. (Rebecca Kelly/CBC)

On the other hand, you have Rocky View County’s council, which in September voted 6-1 to reject a plan for an AI data centre complex (which would have been operated by eStruxture), citing concerns about its proposed location and potential impacts on neighbouring farmers.

“I think data centres do have a public perception problem, and I think there are many Albertans who are beginning to realize not only the question of where is the power coming from for these data centres … but I think the other big question is water,” said Perić.

In an interview with CBC News at CAL-2, Hammond said the industry is being “painted with a broad brush.” That perception, he said, may come from other data centre providers who consume a lot of water and power, and create noise or drive up electricity rates for those near the facilities.

“If you take a look at the site that we’re sitting in today, you’ll notice that it’s quiet, it’s clean, it’s not consuming water,” said Hammond.

Not all data centres have to use water, but there’s a trade off

Data centres have been criticized for their massive water usage, primarily because of the liquid cooling systems many facilities use to keep servers from overheating.

Mid-sized data centres can consume more than one million litres of water a day for cooling purposes, according to a U.S.-based study from June. That’s equivalent to the daily water use of 1,000 households. Often, it’s potable water drawn from municipal utilities.

But a centre like CAL-2 doesn’t use any water in its cooling system, according to Hammond. The building instead relies on air cooling, which in the winter can mean pulling in the cold Alberta air. The only water this facility uses is for sanitation and humidification, Hammond said.

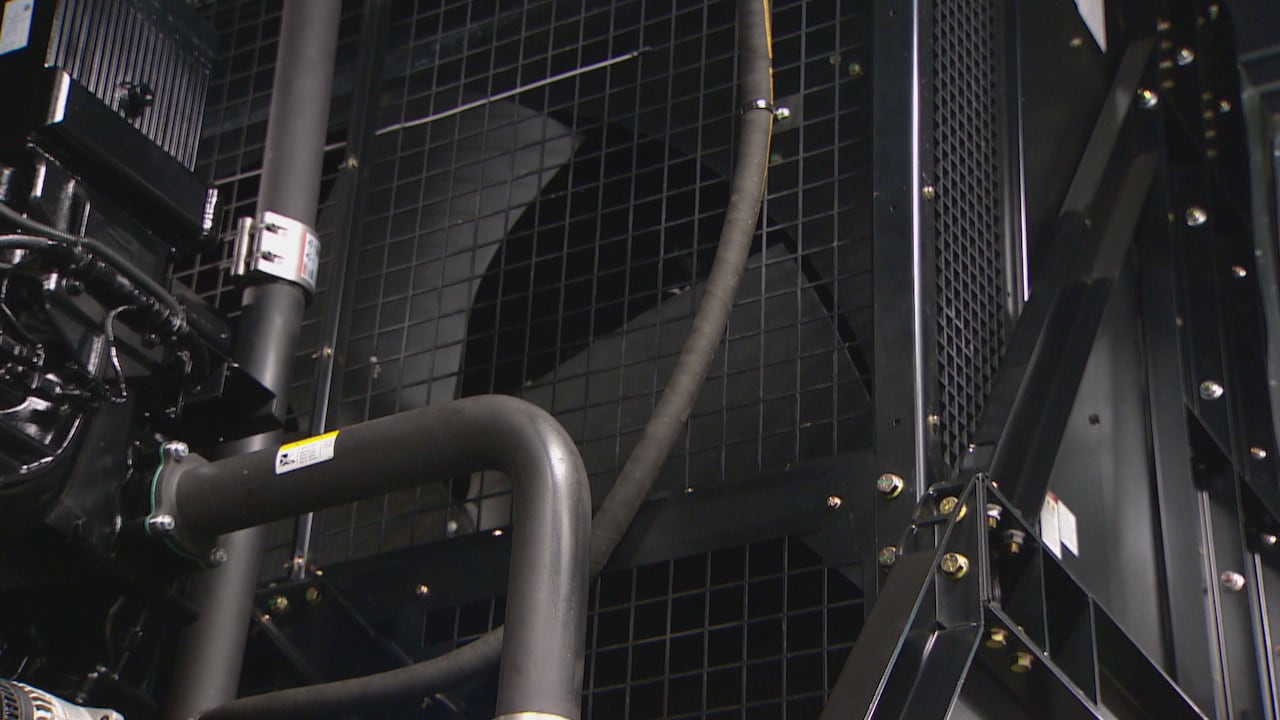

CAL-2’s air cooling equipment, pictured on the left, brings cool air into the data hall’s storing racks of computer servers. (Rebecca Kelly/CBC)

CAL-2’s air cooling equipment, pictured on the left, brings cool air into the data hall’s storing racks of computer servers. (Rebecca Kelly/CBC)

But the future CAL-3 data centre, with its massive campus, will host AI servers that need to run bigger workloads, making them hotter, which in turn require more effective liquid cooling methods combined with air cooling. Still, eStruxture said CAL-3’s closed-loop piping systems will be filled with a pre-mixed glycol solution, and “water will not be used, consumed or evaporated in the data centre cooling process.”

A rendering of CAL-3, which will have three times the capacity of CAL-2 and host AI servers. (eStruxture)

A rendering of CAL-3, which will have three times the capacity of CAL-2 and host AI servers. (eStruxture)

But less water consumption doesn’t necessarily make for a greener data centre, said Noman Bashir, a computing and climate impact fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. With different cooling techniques, he said, comes a trade-off.

“Air-based cooling is less energy efficient than water-based cooling, so if you are avoiding water usage you are stressing the energy … demand and incurring more energy usage,” he said.

WATCH | Cooling data centres requires massive amounts of electricity:

The AI data centre boom is coming to Canada — and it’s thirsty

In a place like Alberta where water is a scarce resource, Bashir said it may make more sense to go with the less energy efficient option and optimize the cold climate.

The task of making data centres more sustainable, Bashir said, is complex and requires companies to make hard trade-offs.

Bigger data centres, more energy demand

The 26-megawatt CAL-2 facility is considered a mid-capacity data centre. Thirty years ago, it would have been considered huge.

Now, with generative AI fuelling demand for bigger and better facilities, the 90-megawatt CAL-3 will be considered a hyperscale data centre. It will be the largest in Alberta once it’s running, drawing power from the provincial grid.

According to Synergy Research Group, the number of hyperscalers now accounts for 44 per cent of the worldwide capacity of all data centres. Looking ahead to 2030, the research firm projects that hyperscale operators will make up the majority of data centres.

A car drives past a building of the large Digital Realty Data Center in Ashburn, Va. (Leah Millis/Reuters)

A car drives past a building of the large Digital Realty Data Center in Ashburn, Va. (Leah Millis/Reuters)

“If we are talking about the current pace at which we are trying to scale AI models and the demand and apply it everywhere, it would be very hard to do that sustainably in U.S.,” said Bashir.

But Canada may have an advantage in that it’s just now looking at building out hyperscalers with massive power needs.

“Sometimes when you adopt a technology a bit later, you may be able to skip a generation or two,” Bashir said.

Alberta currently has no data centres of that size, but many of the proposed projects are pitching to be hyperscalers.

And while the province has no electricity from its grid to allocate to these projects at the moment, Alberta is planning to incentivize companies to generate their own power.

At CAL-2, servers are stored in cabinets (server racks), with each cabinet capable of supporting up to 20 kilowatts of electrical load. Cabinets that hold AI servers can reach from 100 to 150 kilowatts and are expected to become even denser as technology evolves, according to eStruxture regional manager Norbert Mazur.

A backup generator ensures that if the provincial grid connection ever fails, the data centre can keep the lights on and servers running. The cost of not having a redundancy plan could mean big losses for tech companies as websites, IT applications and commerce would be disrupted from even a few seconds of an outage at a data centre.

A backup generator on-site ensures CAL-2 has an uninterrupted power supply to keep the servers running. (Rebecca Kelly/CBC)

A backup generator on-site ensures CAL-2 has an uninterrupted power supply to keep the servers running. (Rebecca Kelly/CBC)

In Alberta, many proposed projects that have suggested their own power generation have planned to rely on natural gas. To make data centres more sustainable, Bashir said renewable and low-carbon energy methods would be key, including small modular reactors.

Hammond said those are on eStruxture’s radar, and something the power team is actively planning for.

Still, cleaner technologies and power generation methods may not be able to counteract the overwhelming demand for AI infrastructure over the coming years, Bashir said, invoking an economics principle called the Jevons paradox.

“If you make something more efficient, the net demand for it does not go down; instead, it goes up. And that is the case with the AI,” he said.

“Purely from the environmental standpoint, your energy usage is going to go up, and that energy will come, at least in the short-term, from gas-based generation resources.”