Stanford University researchers say they have developed a nanoscale optical device that could shift the direction of quantum communication.

Unlike today’s quantum computers that operate near absolute zero, this new approach works at room temperature.

The device entangles the spin of photons and electrons, which is essential for transmitting and processing quantum information.

“The material in question is not really new, but the way we use it is,” says Jennifer Dionne, professor of materials science and engineering and senior author of the paper.

“It provides a very versatile, stable spin connection between electrons and photons that is the theoretical basis of quantum communication.”

She notes that electrons typically lose their spin too quickly for reliable use.

Twisted light and quantum spin

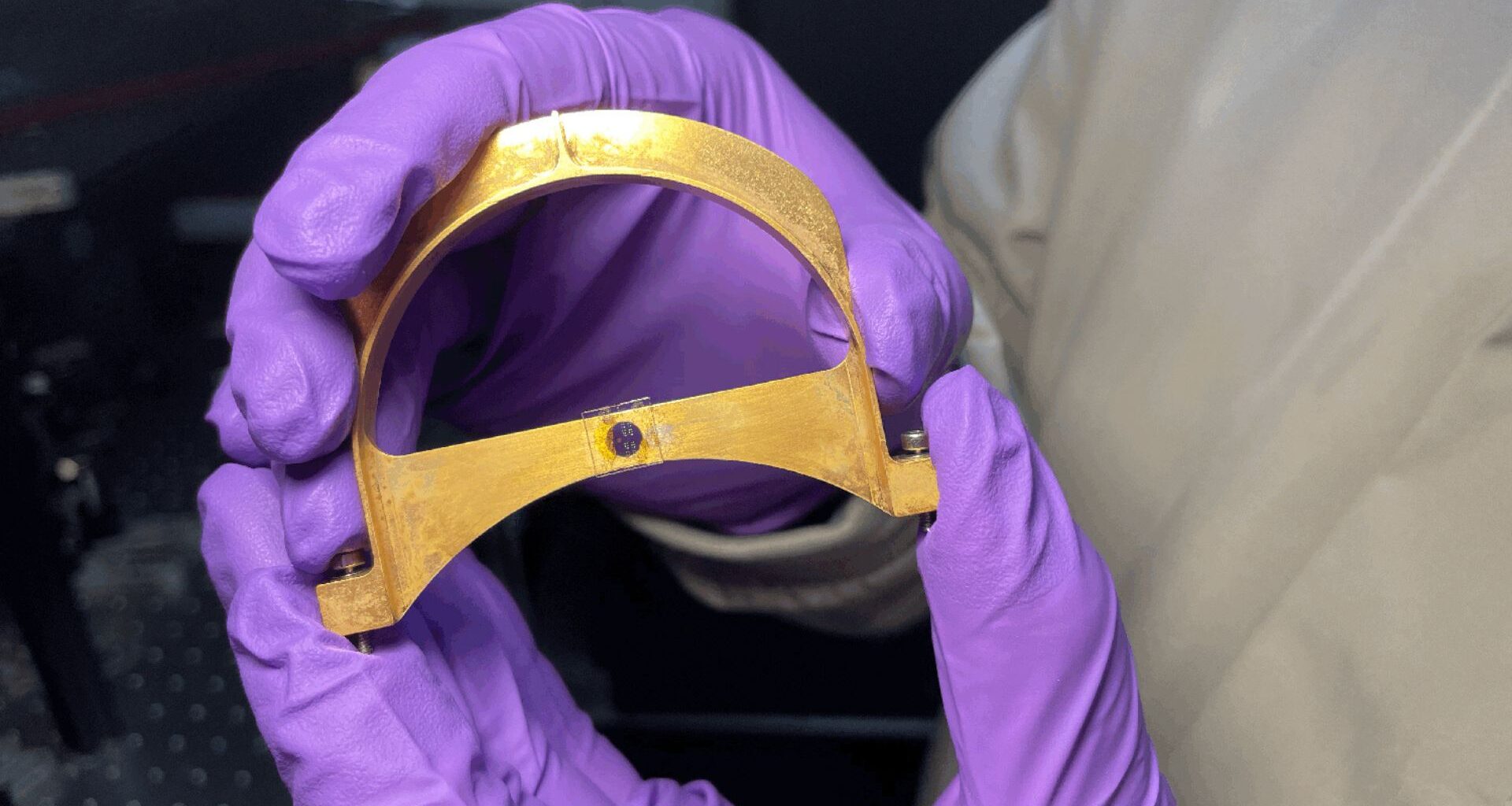

The device combines a patterned layer of molybdenum diselenide placed on a nanopatterned silicon chip.

The material belongs to a class known as transition metal dichalcogenides, which are known for their strong optical responses.

“The Silicon nanostructures enable what we call ‘twisted light,” says Feng Pan, a postdoctoral scholar and the study’s first author.

“The photons spin in a corkscrew fashion, but more importantly, we can use these spinning photons to impart spin on electrons that are the heart of quantum computing.”

Dionne explains that the patterns created on the chip are extremely small.

“The patterned nanostructures are imperceptible to the human eye, about the size of the wavelength of visible light,” she says.

Pan adds that this twisted light can entangle with electron spins to create qubits, which serve as the building blocks of quantum communication.

The spin of a qubit functions much like the zeros and ones in traditional computing, but with far more complexity.

Smaller and more practical

Traditional quantum systems must remain extremely cold to avoid decoherence, which causes qubits to lose their quantum behavior.

That requirement makes existing systems large, expensive, and limited to specialized laboratories.

The Stanford researchers believe their design moves the field closer to practical and accessible quantum technology.

Room-temperature operation reduces cost and complexity. The researchers say this could eventually drive applications in secure communications, artificial intelligence, advanced sensing, and computing.

Pan says the functional pairing of TMDC materials and silicon was a key factor. “It all comes down to this material and our Silicon chip,” he says.

“Together, they efficiently confine and enhance the twisting of light to create a strong coupling of spin between photons and electrons.”

Dionne and Pan are now working to improve the device and are testing other material combinations that may offer stronger performance.

They are also studying how the platform could connect to larger quantum systems.

That transition will require new light sources, detectors, interconnects, and other supporting hardware.

“If we can do that, maybe someday we could do quantum computing in a cell phone,” Pan says. “But that’s a 10-plus-year plan.”

The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.