For devotees, coil shocks promise performance that just can’t be matched by air-sprung alternatives. But, while there are many shock options, most of us don’t think twice about using the spring that comes with a shock, beyond making sure it’s the correct weight. Helix Coil Springs, out of Nelson, B.C., is finally giving the unassuming coil the attention it deserves with the help of some Japanese metallurgic magic.

We talked to Kevin McEvoy about what drove him to make a high-end coil company, why he thinks more riders should take the role of a coil more seriously and the science behind Alex Volokov’s 666 lb signature spring.

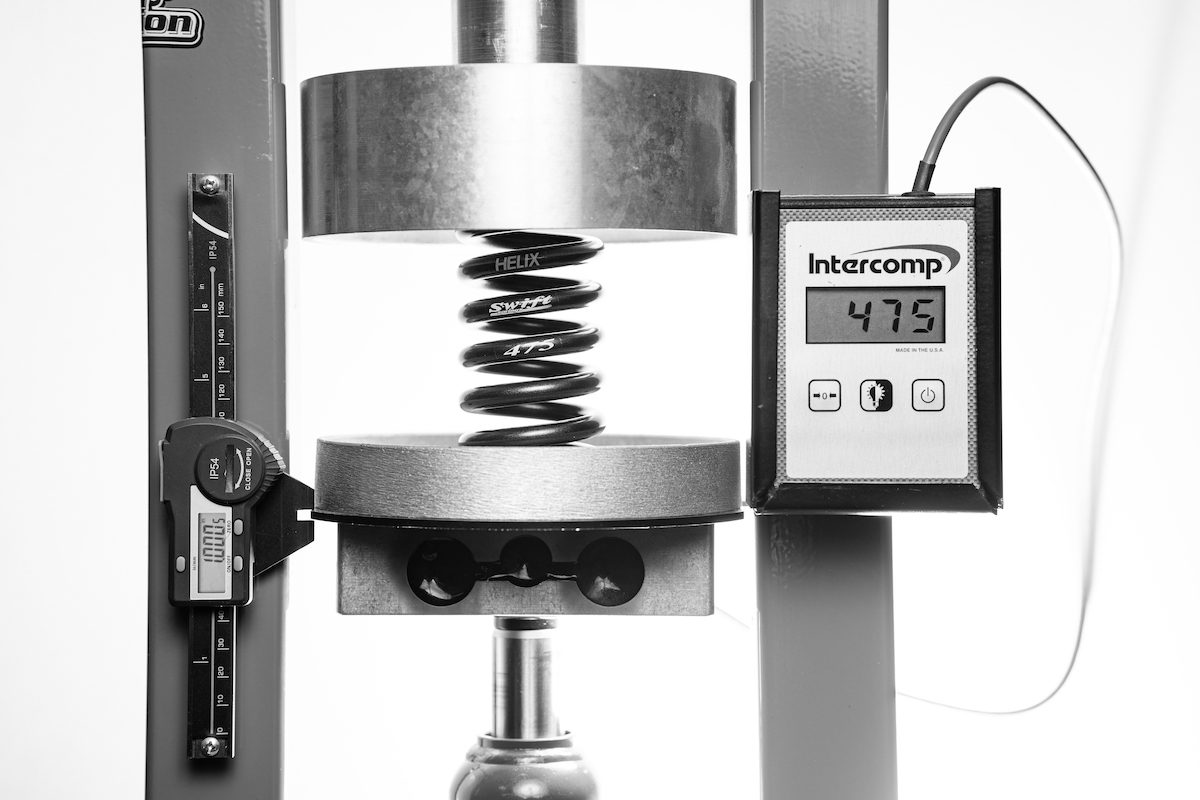

Helix checks each spring before shipping it. Photo: Dustin Lalik

Helix checks each spring before shipping it. Photo: Dustin Lalik

The unassuming coil? Or wrongfully overlooked?

Cycling, as a sport, spends a lot of money on bikes. As mountain bikers, we can spend a lot of money on shocks, even when we do so indirectly through the very expensive frames we buy. The shock at the heart of that frame is, quite directly, what controls whether the frame works as promised or …not.

McEvoy, founder of Helix and the man behind Nelson, B.C.’s Interior Suspension, says that we might not be getting quite the level of quality we assume when it comes to coil shocks. Or, specifically, the coil itself. As the service centre for several high performance brands and working with most major brands, Interior Suspension sees a high volume of coil shocks. Measuring the coils themselves as part of a service, McEvoy says, showed the spring rates weren’t always as advertised.

“There is a pretty big spectrum in quality of a coil spring. With OEM shocks, we’re seeing from 9 to 11 per cent variance in spring rate accuracy, on average.”

When you consider average spring rates on a mountain bike are 350-500lbs, or more, that’s not a minor variance. With Helix offering springs in 25-lb increments, it’s one to two entire spring rates.

“I think the bigger issue is the inconsistency and variability,” McEvoy adds. “If it was always off by the same amount every time, that’s not a big deal. You could plan for that. But with them not being consistent, that’s an issue.”

An issue that has a direct impact on the performance of these very expensive bikes we invest in.

“If you zoom out and look at how much focus we put into the bikes we’re riding and all the deferent technology on a bike. I think suspension is one of the aspects that, if I was to take your bike and really mess with your settings, it’s going to have the largest effect on how your bike performs,” McEvoy argues. “So we’re putting all this focus and energy into making these bikes as high performance as possible, but this major aspect of them is, if you look at those accuracy rates, is this wavering number that’s constantly moving.”

Helix x Alex Volokhov 666lb signature coil

Helix x Alex Volokhov 666lb signature coil

Volokhov and the 666 signature coil

That inaccuracy is, in a way, what led to the 666 lb Alex Volokhov signature spring. While Helix is new, launching just months ago after a few years in development, the Nelson-based pro freerider already trusts the brand for his coil sprung needs. That 666 lb signature spring, which is actually 666lbs, wasn’t just a random fun number.

It started with Volokhov looking for a heavier shock for events like Rampage and Dark Fest. The 700 lb coils he was using for events like Dark Fest weren’t cutting it. So he brought a bunch in to Interior Suspension and, to everyone’s surprise, most measured between 620 and 630 lbs.

“So I asked him how much stiffer he wanted. He was aiming for around 50lbs. So we settled on 666,” McEvoy says. “The idea being that a 666 lb spring that is actually accurate is going to be stiff than his his 700 pound springs.”

The devil is, as always, always in the details.

Photo: Dustin Lalik

Photo: Dustin Lalik

Taking mountain biking seriously

The apparent lack of attention to detail is mountain biking that Interior Suspension found when measuring shocks is, from a wider view, kind of understandable. Mountain biking, while growing, isn’t the hugest market. Especially when you narrow that down to bikes with coil-sprung shocks and then compare it to motor sports, where vastly more coil springs are being used.

Part of the problem is that mountain biking inverts the usual relationship between human and machine. Being based in Nelson, Interior Suspension does a lot of work on snow sports during the winter making snowmobiles the obvious comparison. The weight of a snowmobile is significantly more than the rider, whereas the weight of a bike is significantly less than the weight of a a rider.

For motorsports, suspension is designed around the weight of the machine. In Mountain biking, suspension needs to be optimized for the weight of the rider. And, compared to a thousand-pound motorized machine, a much smaller change in spring rate can have a very noticeable impact on the rider’s experience. So, while small variations in spring rate might not be as noticeable in other realms, the inconsistency McEvoy is finding in OEM springs really is important to mountain biking.

Helix’s goal is to take the lowly coil’s role in the ride experience more seriously. That mean’s designing coils specifically for mountain biking, just as shocks are designed for bikes. To do that, McEvoy and Helix looked to Japan.

Photo: Dustin Lalik

Photo: Dustin Lalik

Meet Swift: The Japanese brand take steel very seriously

To get coils made to the standards McEvoy thinks should be standard for the industry, Helix works with Swift. The Japanese brand is one of just a handful of high-end spring manufacturers in the world.

“The thing that really sets Swift apart is that they are the only spring manufacturer in the entire world, even amongst those other very high level spring manufacturers, that own their own steel mill,” McEvoy explains, adding, “The part that makes them really cool is that they describe themselves as a metallurgy company first and a coil spring company second.”

Owning the mill gives Swift remarkable control over quality and consistency of its coils, compared to brands that are building their coils from steel purchased from someone else.

“Another issue that is less talked about with coil springs is in production. The coil is wound into a coil spring. That builds up quite a bit of stress in the spring. That stress needs to be relieved through, usually a heat treatment process and a shot pending process,” McEvoy explains. “But if all those processes aren’t very tightly controlled, you can get softer and stiffer sections in the spring. Also, if a brand is buying a steel from someone else, often in spools of hundreds or thousands of feet, you can get little diameter changes throughout the spool, and little quality control issues.”

Having its own mill also gives Swift the ability to optimize the alloy it uses for different purposes. It’s HS5.TW alloy is designed specifically for off-road use.

In one final touch, McEvoy points out that the colour of the spring isn’t paint or even anodizing. Swift impregnates the pigment into the steel during the milling phase, something owning its own mill allows only the Japanese brand to do.

Kevin McElvoy. Photo: Dustin Lalik

Kevin McElvoy. Photo: Dustin Lalik

Made by Swift, made for Helix

Coils made for Helix aren’t just Swift springs, though. McEvoy worked with the brand, going back and forth for a year, to optimize Helix coils for the unique demands of mountain biking, down to the alloy used to make the springs.

“The off-road alloy is tuned, optimized to respond quickly under load, essentially to be more active,” McElvoy says. That alloy is then used to design a spring around how a shock moves on a bike.

“If you’re looking at where a coil spends most of its time in its travel, you can actually optimize the spring around that space. On mountain bikes, that’s generally around 30 per cent sag,” McElvoy explains, compared to an automotive where that number might be closer to 10 per cent. “You can also optimize it around the kind of forces and shaft speeds that a coil on a mountain bike sees.”

That makes a Helix coil a truly mountain bike specific part, not just a generic spring. All that adds onto the impressive accuracy with which Swift is able to produce shocks. Helix tests every coil before it’s sold. McEvoy says they’re seeing springs measure with 1.3-1.5 per cent of the claimed spring rate.

“Swift is also maintaining that accuracy anywhere in its travel,” McElvoy adds. “With many OEM shocks, if you test at different parts of the coil you get drastically different numbers. With Swift, you’re not getting any softer sections or quality control issues.”

Those irregularities, McElvoy points out, then interact with the kinematics of your frame. And that can happen in unpredictable ways.

ToughCast finishing touches

The final touch on a Helix spring is the adaptor. This not only lets a Helix coil work with a wide, and expanding range of shocks, but adds performance. The adaptor is made out of ToughCast, a material that works partially as a solid lubricant.

“When people call it plastic, I’m like “wow wash, it’s not plastic. This is engineered polymer,” McEvoy says with a laugh. “Truthfully, I could have chose a much cheaper material. And I did look at other materials. But for its characteristics, there’s nothing better I could find.”

The material, similar to what’s used by Push on its shocks, works with the coil’s natural rotation as it compresses instead of fighting it. This prevents binding between the pre-load collar and the spring. It also helps quiet any creaking some might experience on a coil.

A little effort to change. A lot of performance gained. Photo: Dustin Lalik

A little effort to change. A lot of performance gained. Photo: Dustin Lalik

The future is coil

If you haven’t guessed by now, McEvoy is a coil advocate, both though Interior Suspension and, now Helix.

“I’m just a massive fan. I think the feeling of reduced friction and the ability to react to small bumps is always a benefit. If you can reduce the friction in the system, that’s always.a win. There’s no downside to that,” McEvoy says. “If coil’s well set up for you, it’s pretty hard to go back, right?”

Air springs, though, are still dominant. McEvoy argues this is as much to do with convenience as the quality of performance.

“The challenge is that you need to physically change springs,” McEvoy explains “We all said weight was the big thing, but I think that’s the real reason the bike industry has favoured air suspension. Bike shops had to stock all those coil springs. All the different brands and different lengths and different rates, it turns into an inventory nightmare for the average bike shop.”

Coil, he argues, should be getting more attention for the performance gains it offers.

“I know that in B.C., especially here in Nelson, we definitely are in a more gravity oriented part of the bike world,” McEvoy admits. “But I think people are coming around. They’re not so worried about every little bit of weight and are thinking about how we can get our bikes to perform better? Feel really good, you know?”

The vast improvements in bike design, McEvoy thinks, are opening up more room for springs to, well, return.

“Now, bikes are so light that you can actually afford to add some weight to your bike if it’s going to have a significant performance increase,” McEvoy says. “I think coil suspension is one of those things.”

”I use the term weight well spent.”