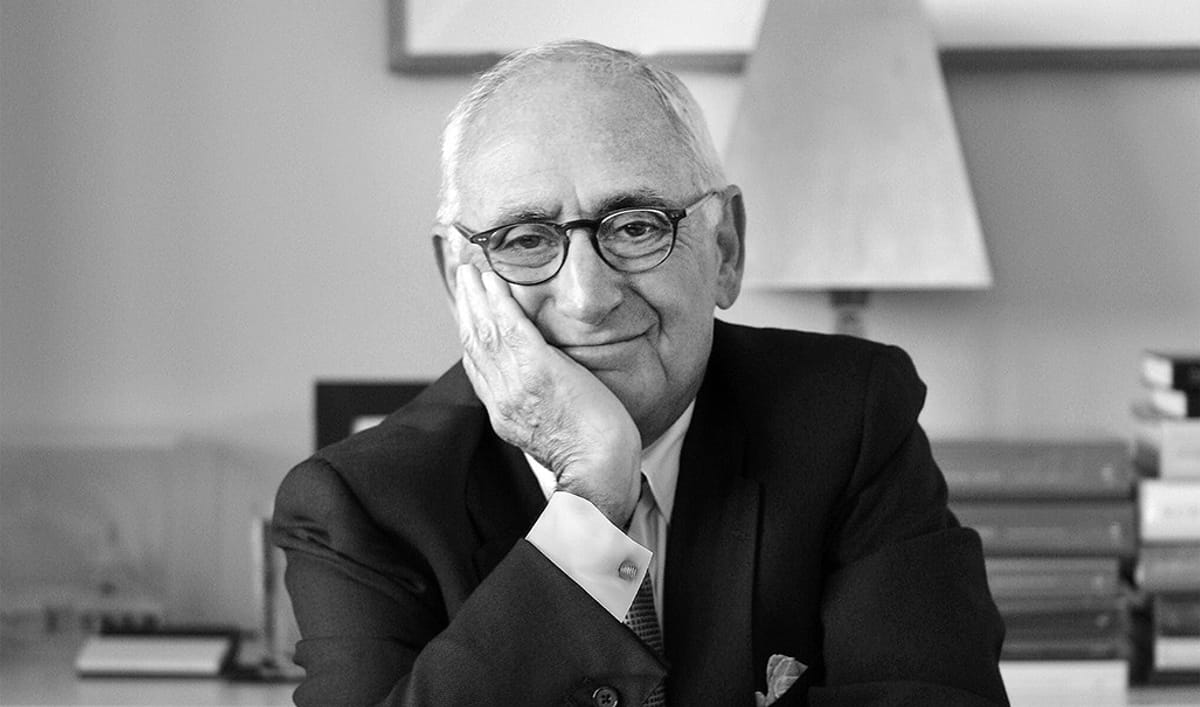

Robert A.M. Stern. Image courtesy of Yale University

As the architectural community reacts to the death of prominent American architect and educator Robert A.M. Stern, we reflect on the career of the self-described ‘modern traditionalist’ and his impact on the design, teaching, and discourse of architecture.

Tributes and memories

One week after prominent architect and educator Robert A.M. Stern passed away at 86, tributes have poured in from across the architectural community.

“The sad news of Bob Stern’s death last Thursday marked the end of an era in architectural culture in New York,” said Rosalie Genevro, former executive director of the Architectural League of New York. Stern became the youngest-ever president of the league’s board in 1973. “Certainly, Bob was known and influential far beyond the boundaries of the city, but his passion for architecture was formed here, and the projects that grew out of his instinctive attraction to New York’s genius loci, and lifelong curiosity about and advocacy for it, will form a major part of his legacy.”

A visionary architect, educator, and thinker, his influence shaped generations and redefined the dialogue between tradition and modernity. — Ma Yansong on Robert A.M. Stern

“Well known for his energy, he seemed to be everywhere at the same time,” Yale University said in memory of their former architecture dean. “Someone once claimed that she spotted him on East 65th St. in New York City at the same time someone else was certain she saw him walking up Chapel Street in New Haven. Knowing him, they said it was always possible that he was at two places at the same time.”

Prominent architects have also expressed sadness at Stern’s passing. MAD Architects founder Ma Yansong shared photographs with Stern at Yansong’s Yale graduation, while Deborah Berke, Stern’s successor as Yale architecture dean, wrote that “he was principled, he was generous, and he was fun. For him, nothing was more important than architecture and architectural education, and nothing was more fun than talking about design with a martini in hand.”

The modern traditionalist

Such thoughts and tributes shared about Stern, including by Archinect readers, underscore the unique philosophy Stern brought to the profession. Emerging from his education at Yale as a postmodernist, he would later describe himself as a champion of “modern traditionalism,” who sought to “put back into architecture what orthodox modernism had taken out of it,” and “reinventing and reinvigorating the free-spirited modern classicism that had been erased from history books by strict modernists.”

RAMSA sought an approach that “looked to the future while incorporating architectural history and the complexities of place as a dynamic and essential foundation for design.”

Stern worked for over five decades to bring his architectural philosophies to cities in and beyond the United States. In Philadelphia, Stern designed the Comcast Center as a prismatic glass curtain wall office tower that echoes the proportions of the classical obelisk, while in New York City, Stern’s 15 Central Park West scheme was praised as recapturing the “spirit of New York’s great pre-war apartment houses.” In Texas, Stern designed the George W. Bush Presidential Center clad in brick and Texas Cordova Cream limestone along classical principles of colonnades and enveloping wings surrounding a central courtyard.

Stern delivered on his philosophies through the vehicle of Robert A.M. Stern Architects (RAMSA), which he founded in 1969. Established from the beginning as a “departure from the modernist conventions of the 1960s,” RAMSA sought an approach that “looked to the future while incorporating architectural history and the complexities of place as a dynamic and essential foundation for design.” Today, the New York City firm employs over 200 people on projects across all typologies and geographies.

Tour Carpe Diem by Robert A.M. Stern Architects. Image courtesy of CTBUH.Yale’s galvanizing dean

Tour Carpe Diem by Robert A.M. Stern Architects. Image courtesy of CTBUH.Yale’s galvanizing dean

Stern’s achievements in practice were matched by those in academia. Having previously taught at Columbia University, Stern returned to Yale in 1998 to take on the role of architecture school dean at the university from which he earned his master’s degree in architecture in 1965. The appointment was not without controversy. The committee tasked with choosing the dean feared that Stern’s defence of historical architectural styles would be too backward-looking to attract students if Stern were to seek to sculpt the school’s teaching along his own architectural philosophies. When Stern was introduced to the faculty as the new dean, some left the announcement in protest.

Instead, in the words of former Yale president Richard Levin, Stern arrived at the position with the aim of making Yale a “wide-open arena for discussion, where every interesting approach to architecture was tested and debated.” Levin, who ultimately hired Stern for the role, added that Stern was “the smartest, most intellectual, and most articulate architect I had ever encountered.”

We’ve enthusiastically continued that approach at the school. Discussion, along with commitment to excellence and heartfelt hospitality, continue to shape how we teach architecture at Yale. — Deborah Berke on Robert A.M. Stern

Throughout his tenure as dean from 1998 to 2016, Stern sought to bring a diverse range of prominent architects to the school as visiting critics and speakers. Among those were Philip Johnson, Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Norman Foster, Deborah Berke, and Bjarke Ingels. Stern also revived the school’s student-led journal Perspecta, started the architecture magazine Constructs, and oversaw the creation of a historical archive for architecture at the university. Stern also championed the use of modern tools for students and faculty in their work.

“Bob loved an informed opinion and a rigorous debate,” Stern’s successor Deborah Berke told Yale for its tribute to Stern, one which described him as a ‘galvanizing dean’ for the school. “We’ve enthusiastically continued that approach at the school. Discussion, along with commitment to excellence and heartfelt hospitality, continue to shape how we teach architecture at Yale.”

Robert A.M. Stern. Image credit: Peter Aaron/OTTOPraise and controversies

Robert A.M. Stern. Image credit: Peter Aaron/OTTOPraise and controversies

Stern’s embrace of ‘modern traditionalism,’ and the initial unease created by his appointment as Yale’s architecture dean, speak to Stern’s willingness to engage with controversial and emotive issues. In 2013, Stern wrote a foreword for Léon Krier’s book Albert Speer: Architecture 1932-1942; a book which attracted criticism from critic Michael Sorkin, asking “why bother to defend Speer as an architectural talent?” After Stern’s death, Archinect readers continued to debate Stern’s decision to write a foreword for the book. The same year, Stern also refused to sign a petition to grant Denise Scott Brown a joint Pritzker Prize with Robert Venturi, saying that while he backed the principle, he objected to the petition’s use of the word “demand.”

Bob Stern has brought classicism into the public realm and the mainstream of the profession, reinvigorating it for generations to come. — Michael Lykoudis on Robert A.M. Stern

Such controversies did not stop Stern from being honored with a long list of architectural accolades. The AIA made Stern a fellow in 1984, while in 2017, the AIA and ACSA jointly honored Stern with their Topaz Medallion. A fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences and a member of the American Academy of Arts & Letters, Stern has also been given various honors by organisations such as the Architectural League of New York, Sir John Soane’s Museum, and the American Academy in Rome.

In 2011, the University of Notre Dame honored Stern as the 2011 laureate of the Richard H. Driehaus Prize. At the time, Notre Dame dean and prize chair Michael Lykoudis said: “More than any other practicing architect today, Bob Stern has brought classicism into the public realm and the mainstream of the profession, reinvigorating it for generations to come.”