Listen to this article

Estimated 5 minutes

The audio version of this article is generated by text-to-speech, a technology based on artificial intelligence.

Advocates working with victims of conjugal violence on Quebec’s North Shore say more work needs to be done to ensure tools and measures to help victims are adapted to the realities of the region.

In 2022, the provincial government introduced the use of electronic tracking bracelets to ensure the safety of victims of intimate partner violence.

The tracking equipment is composed of a bracelet for the offender and a mobile device application that allows the victim to monitor the suspect’s movements with an alert sounding if the accused is within a certain distance.

According to government data, in the period since the program’s implementation in May 2022 up to the end of September of this year, 1,270 bracelets were issued with a deterrence rate of just over 96 per cent.

The government says the findings show the anti-proximity bracelets are an “effective means of protection for victims,” but some advocates say while a useful tool, the bracelets have their limitations in the province’s remote regions.

Meanwhile, a 2022 study by Quebec’s Public Security Ministry shows the Côte-Nord has the highest rates in the province when it comes to infractions committed against a person in a conjugal context.

Small communities, reliability issues on North Shore

Louise Riendeau, a spokesperson for the Regroupement des maisons pour femmes victimes de violences conjugales — a Quebec advocacy group with a network of shelters for women, says one issue is that not all regions of Quebec have good cellular or internet coverage which can impact the reliability of the device.

The other challenge is that the bracelets aren’t necessarily adapted to the realities of small communities like those on the North Shore, where it can be difficult to avoid close proximity.

“When you’re in a village where there’s only one road that everyone has to use, it’s quite possible that an offender will pass near their victim’s house and therefore trigger alerts,” Riendeau said.

She said in those circumstances, it can actually become more of a disturbance than a protective measure.

Marie-Hélène Talbot, head of the regional Crime Victims Assistance Centre (CAVAC), told Radio-Canada’s Côte à Côte earlier this week that tracking bracelets can not only help victims feel safe again but help them regain some freedom.

Still, none are currently being used in Quebec’s Côte-Nord region, she says, adding it’s not the measure most frequently used for offenders in the area.

Change of directive for probation officers

Both Riendeau and Talbot expressed further concern for the safety of victims after learning of recent changes in directives for probation officers regarding the frequency of follow-up visits with offenders and victims.

Under the new measures, according to the Public Security Ministry, probation officers can reduce check-ins for offenders to once a month, down from twice a month, whereas follow-up visits for victims will no longer be imposed to prevent a feeling of revictimization.

Talbot said bracelets have been used in the past in the region and will probably be used again, but she fears that a lack of regular follow-ups can impart victims with a false sense of security.

She evoked the scenario where a woman is in an area with poor cellular coverage and the offender is aware of that fact. The offender may be feeling out of sorts but hasn’t seen their probation officer in a month.

It can be more dangerous for victims when they think they are safe, but they aren’t, Talbot said.

“We need to ensure that the feeling of security is legitimate.”

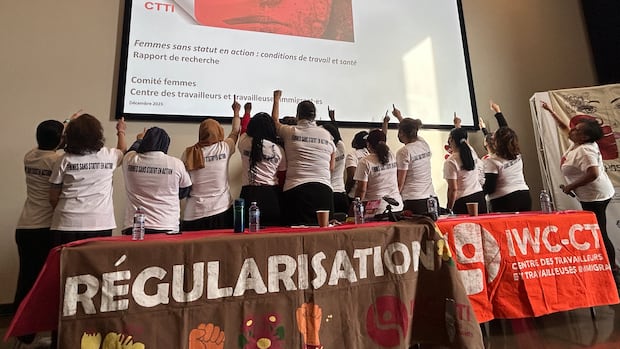

WATCH | Study finds undocumented women workers targets of abuse:

Undocumented women workers in Quebec face rampant exploitation, report finds

A new report by Montreal’s Immigrant Workers Centre highlights challenges facing undocumented women workers, from wage theft to sexual harassment.

Advocates say that in a context where monitoring bracelets can’t always be used, visits with probation officers are essential — even for victims.

The worry is that without systematic contact with victims, probation officers might miss some red flags that could indicate an increased risk, such as the victim entering a new relationship.

“It’s therefore important to be able to talk to victims and have that information, to make sure that the measures that have been put in place are effective and will succeed in protecting them,” Riendeau said.

In an email to CBC News, Quebec’s Public Security Ministry said probation officers should use their own discretion when deciding on the frequency of their visits with clients.

The ministry, however, specified that a reduction in visits should not occur if it is “likely to jeopardize public safety, particularly in the presence of a significant and present risk of violence,” it reads.

The ministry said the measures are meant to reduce probation officers’ workload and allow them to focus on cases requiring more attention, without impacting the safety of victims.

Furthermore, while follow-up visits with victims are no longer imposed, the ministry said victims are free to reach out to a probation officer at any time.

WATCH | Polytechnique expands scholarship program to 14 women in memory of 1989 tragedy :

14 female engineers awarded scholarships in honour of École Polytechnique victims

For the first time, Montreal’s École Polytechnique awarded post-graduate engineering scholarships to 14 women, the same number killed at the institution on Dec. 6, 1989. The Order of the White Rose was created in memory of the 14 female engineering students shot and killed in the anti-feminist attack.