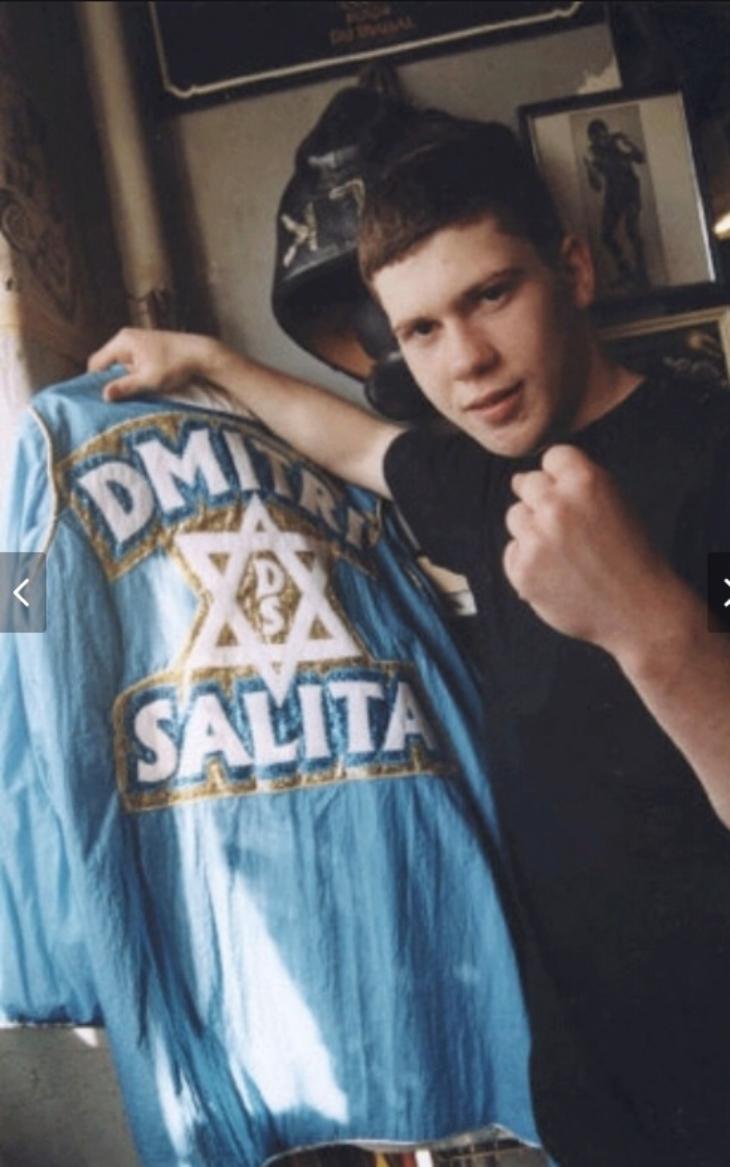

The year was 2000. Dmitry Salita, a young Jew and immigrant from Ukraine, was making his ways up the ranks in boxing. After training under the legendary Jimmy O-Pharrow at Starrett City Boxing Club in Brooklyn, home of many top boxers, Dmitry was invited to compete in the under-19 U.S. national championships.

The only problem? The final was going to be held on Shabbat, and Dmitry is an Orthodox Jew.

“Shabbat is a show of trust in the fact that God runs the world, and we honor that fact by not doing certain things on Shabbat, even if they are very important to us,” Dmitry said.

If Dmitry won his fights, he was going to have to box at 2 p.m. that upcoming Saturday, well before Shabbat ended.

“They said I would be disqualified if I didn’t compete,” he said. “I had a lot of talented boxers in my weight class. I told myself, ‘Let me take it one day at a time.’”

“They said I would be disqualified if I didn’t compete,” he said. “I had a lot of talented boxers in my weight class. I told myself, ‘Let me take it one day at a time.’”

Throughout the week, Dmitry kept winning his fights and made it to the semi-finals and it looked like he was going to be told to compete on Shabbat. In an interview, sports journalist Dylan Hernández asked him, “What can we expect from you in the finals?”

He replied, “I won’t box in them. It’s at two in the afternoon on Saturday.”

Dylan then said to Dmitry, “Let me see what I can do for you.”

And just like that, “the time of my fight was changed,” Dmitry said. “My trainer, Jimmy, said the Lord works in mysterious ways. I had no idea how it happened, and I still don’t.”

Dmitry went on to compete in and win the U.S. national championship. He was then invited to fight in the New York Golden Gloves at Madison Square Garden, which was going to be on a Friday night.

“Then, they changed it to Thursday, and I won,” Dmitry said. “I got the Sugar Ray Robinson Award for outstanding boxers. I turned professional.”

He signed the first professional contract in sports stating that none of his fights would be scheduled on Shabbat or Jewish holidays.

Dmitry started working with Bob Arum, a promoter who also worked with George Foreman, Manny Pacquiao, and Oscar De La Hoya. He signed the first professional contract in sports stating that none of his fights would be scheduled on Shabbat or Jewish holidays.

“I have gratitude for the fact that there is such a day that has helped generations of Jews stay connected to our faith,” he said. “I believe this is one of the greatest gifts God has given us.”

Humble Beginnings

Dmitriy and his family left Ukraine in 1991, after the fall of the Soviet Union, and during the second wave of Soviet Russian Jewry emigrating to the U.S. In the Ukraine, they had experienced antisemitism.

“My father would get passed over for promotions because he was Jewish,” he said.

Dmitry and his family, who were not religious, moved to Flatbush, Brooklyn. It wasn’t easy; they were on food stamps and welfare. At the age of 13, he discovered boxing and dove right into it, training with peers at Starrett City Boxing Club who would go onto become world champions.

“My own challenges as an immigrant fueled me,” he said. “I was around kids who had similar financial challenges like I did. We came from different communities and backgrounds, but we found boxing – and I found my people.”

Dmitry was not among other Jews at the boxing club.

“They say the thinnest book in the library is the one on Jewish athletes,” he said. “Jews were the most dominant ethnic group in boxing in the 1920s and 1930s. After the 1940s, though, it really thinned out.”

Discovering His Judaism

The young boxer started doing very well, making his way into the championships. It was clear he had talent. At the same time, he was discovering his Judaism. While he’d always believed in God, he wasn’t traditionally observant. Then, all that changed.

“When I was 14 years old, my mother had breast cancer and was sharing a room in the hospital with a religious lady,” he said. “This lady’s husband came to visit her. We spent the entire day together. They took my information and gave it to a local Chabad rabbi, Rabbi Zalman Liberow of Chabad of Flatbush. Between the difficulties of immigration and school and my mom being sick, I decided I would go there.”

Dmitry found meaning in it and took on religious observance. He asked his rabbi for a blessing.

“He said, ‘I suggest you write a letter to the Rebbe,’” Dmitry said. “The letter I got back was, ‘You will be successful in what you do and have influence over people but do your job according to Torah.’ My rabbi told me, ‘For you, this means you can’t box on Shabbat.’”

Dmitry told his rabbi, “This is a very big request. It’s impossible,” but he trusted in God.

And so, he ended up not having to box on Shabbat throughout his entire prestigious career. At one point, he was invited to the White House and met President Bush and President Obama.

Now, after an accomplished career in boxing, Dmitry is not only a proud husband and father, he is also a successful promoter. He currently represents more than 30 boxers, including world champion Claressa Shields. He works hard and travels for his job, always praying three times a day, keeping kosher wherever he goes, and attending a Jewish class once a week.

“My ultimate goal, professionally, is to continue to grow my business and find meaning in what I do,” he said. “I feel that everybody’s talent is a divine expression. You have to use it responsibly to make the world a better place and influence it in a good way.”