LISTEN | Why we must demand more from architecture :

Ideas54:00Pt 1 | Master of his own Design: Conservations with Frank Gehry

Frank Gehry, arguably the world’s most famous architect, has died at 96. A rebel in his field, he never stopped creating sensual, sculptural buildings which rejected the cold minimalism and glass boxes of Modernism, and the ornate flourishes of Postmodernism.

Gehry became an international celebrity in his late 60s for designing the now-iconic Guggenheim museum in Bilbao, Spain. And with his global fame came the nicknames that Gehry hated almost as much as he seemed to hate the media.

“The damn word, Star’chitect. That was invented by the press. Who would call themselves a Star’chitect? So the press invents a name and then they use it to disparage somebody with,” Gehry told IDEAS producer Mary Lynk in 2017, when he was 88.

LISTEN | What does mortality mean to an artist who can’t stop creating? :

Ideas54:00Pt 2 | Master of his own Design: Conservations with Frank Gehry

Despite his antipathy toward journalists, Lynk had the rare opportunity of spending time with Gehry over a couple of days at his Los Angeles studio. In time the media-wary architect opened up to Lynk.

“There’s one guy who doesn’t even think I’m an architect. He calls me: artist manque. He only likes simple boxes, it’s strange…and I like the guy too, I have fun with him,” Gehry says of a critic he told Mary he will not name.

“He just can’t get over it. I’m sort of an aberration that he wants to obliterate. If he could do it without having to go to jail, he’d do it,” he said, laughing.

WATCH | How architecture made Frank Gehry weep:

Frank Gehry talks about a building that moves him to tears (videographer Andy Hines)

Frank Gehry talks about a building that moves him to tears (videographer Andy Hines)

Gehry was born in Toronto, in 1929, with the name Frank Owen Goldberg. His first wife feared the potential impact of antisemitism on his career, and convinced him to change his last name. It was a common tactic back then, but something he’s embarrassed by.

He struggled for much of his life, from a tough childhood, lifelong therapy sessions to being the perpetual outsider in the world of architecture, a rebel who shuns conformity at any cost in a field that some purists refuse to call an art.

In a two-part series on IDEAS, the renowned architect delved into his life, the influences on him, his family, his personal demons and facing his own mortality.

“Well, I can’t deny that I think about it. Miraculously I’m still walking and swimming and working. I have a lot of friends that hit my age [88] that aren’t here anymore. I was close to Milton [Wexler] all through the years. He told me keep working. He lasted till 98, so that was a good role model, and Philip Johnson as well kept telling me, just keep working, don’t you dare stop. So I think that kind of encouragement from two people I really loved and respected and they’re kind of mentors, I figure skyrocket. That’s how you go out.”

Here is an excerpt from Frank Gehry’s conversation with Mary Lynk.

Why are you more drawn to the company of artists than architects?

I think it was circumstantial maybe. Maybe it would have happened anyway, but when I started working in L.A., something I was doing pissed off the other architects and I couldn’t ever figure it out. There were a bunch of artists who used to come to the job site who I knew their work. I didn’t know them. I was kind of amazed that they were interested in what I was doing so early in my work life. And they started inviting me to their social stuff and we became friends and they were very positive and supportive, whereas the architecture world thought I was crazy or something.

On the walls of Frank Gehry’s office there are several nods to his birthplace, Toronto. Even though Gehry moved to L.A. when he was 18, tucked between art, drawings, architectural models and photos are a slew of framed jerseys of hockey legends, including Matt Sundin, number 13 and a photo of Maurice ‘the Rocket’ Richard, number 9. (Andy Hines)

On the walls of Frank Gehry’s office there are several nods to his birthplace, Toronto. Even though Gehry moved to L.A. when he was 18, tucked between art, drawings, architectural models and photos are a slew of framed jerseys of hockey legends, including Matt Sundin, number 13 and a photo of Maurice ‘the Rocket’ Richard, number 9. (Andy Hines)

I think sometimes it’s like the word Schadenfreude, you know, the German word about when people fall from grace because of jealousy. You were doing something different and architecture sometimes has a movement and you were always jumping the sides of the movement.

I felt comfortable in my own stuff. I understood curiosity and creativity and that it was valuable and that one could explore and one could have a signature. I mean, it was obvious to me when you write your name, somebody else writes their name, you can tell the difference. And hanging out with the artists gave me some confidence in that because they were doing that. I mean. I didn’t copy their work or anything but there was a feeling of whatever they were doing it was different than what the other people were doing and it was really them and they were in touch with it. And there was mutual support in the early days. They then got jealous and did all that stuff later.

You had an issue later with Richard Serra when he said that you can’t have art with plumbing.

Well, I love Richard Serra’s work and I always loved talking to him and we collaborated on a few things but somehow I said the wrong thing or did the wrong thing. I don’t know what I did.

I don’t think you’re the only person with Richard Serra to lose a friendship.

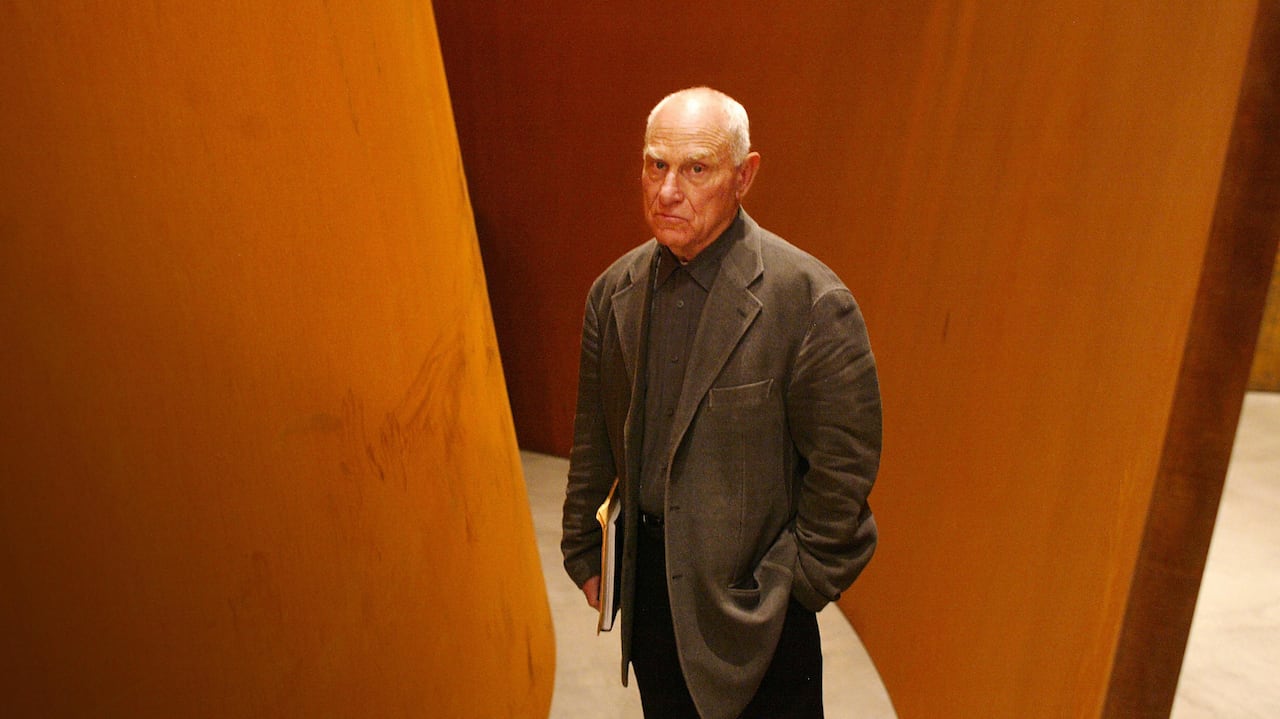

U.S. sculptor Richard Serra in front of one of his most famous works ‘The Matter of Time,’ a series of massive steel ribbon sculptures that curl and weave through the main gallery in the Guggenheim and Bilbao, the museum, designed by Frank Gehry. Serra is adamant in arguing that architecture is not art. (Rafa Rivas/AFP via Getty Images)

U.S. sculptor Richard Serra in front of one of his most famous works ‘The Matter of Time,’ a series of massive steel ribbon sculptures that curl and weave through the main gallery in the Guggenheim and Bilbao, the museum, designed by Frank Gehry. Serra is adamant in arguing that architecture is not art. (Rafa Rivas/AFP via Getty Images)

It’s important, the relationship with a person you’re creating with because I mean you are very creative and there’s a strong artistic element. We’re not gonna call you an artist. We know all that debate between whether architecture is art.

Oh, architecture is an art.

Are you an artist then?

Well, I don’t like to draw the line, so I always say I’m an architect because I don’t want to get into the discussion. I know that’s loaded but when you let that go, in the culture we’re in and you don’t demand that the level of art or whatever an artist does bring your persona into the project like an artist does. You’re giving up. That’s why all the buildings in around the world all look the same, ’cause they’re they’re just giving up.

It’s generic too and is it greed? I mean you look at city cores and they’re all the same and you know what kills me, you have this beautiful architecture, a lot of these museums that are iconic, and these houses. But one percent are for the public. The average person lives in just banal, right? How can we make architecture for everybody?

Well, you have to understand that it’s available, that there are talented people prepared to make it better. But they don’t demand it, and so they accept it. It’s denialism. That’s why I did the chain link years ago. Everybody didn’t understand why I was doing that… I tried to find a material that was the essence of that, that people hated, and I found chain link that was being used, that was being produced ubiquitously all over the world, and they couldn’t make enough of it — and everybody hated it…

WATCH | Deciding to take a leap of faith:

Frank Gehry on why creatives must take risks. (videographer Andy Hines)

Frank Gehry on why creatives must take risks. (videographer Andy Hines)

Do you like chain link? Do you think esthetically it’s beautiful?

I think the way it’s used it’s not. But I did a little shopping thing here where I hung them as curtains and it’s beautiful. They move in the wind and let the light through. There’s nothing wrong with it. Except it’s got a bad rap. And so I thought that’s a sort of a metaphor for how our cities look like they do. People hate it but they don’t do anything about it.

Is it because they don’t realize that architecture is important that you are affected by the buildings that surround you?

If you’re a household that’s living on the margins and, you know, got to put two kids through college and food on the table and I mean I’ve been there myself struggling, you don’t think about art or architecture, you think about survival. So I think we’re asking a lot of people to think about the art of architecture.

Download the IDEAS podcast to listen to this conversation.

*This two-part series was produced by Mary Lynk.