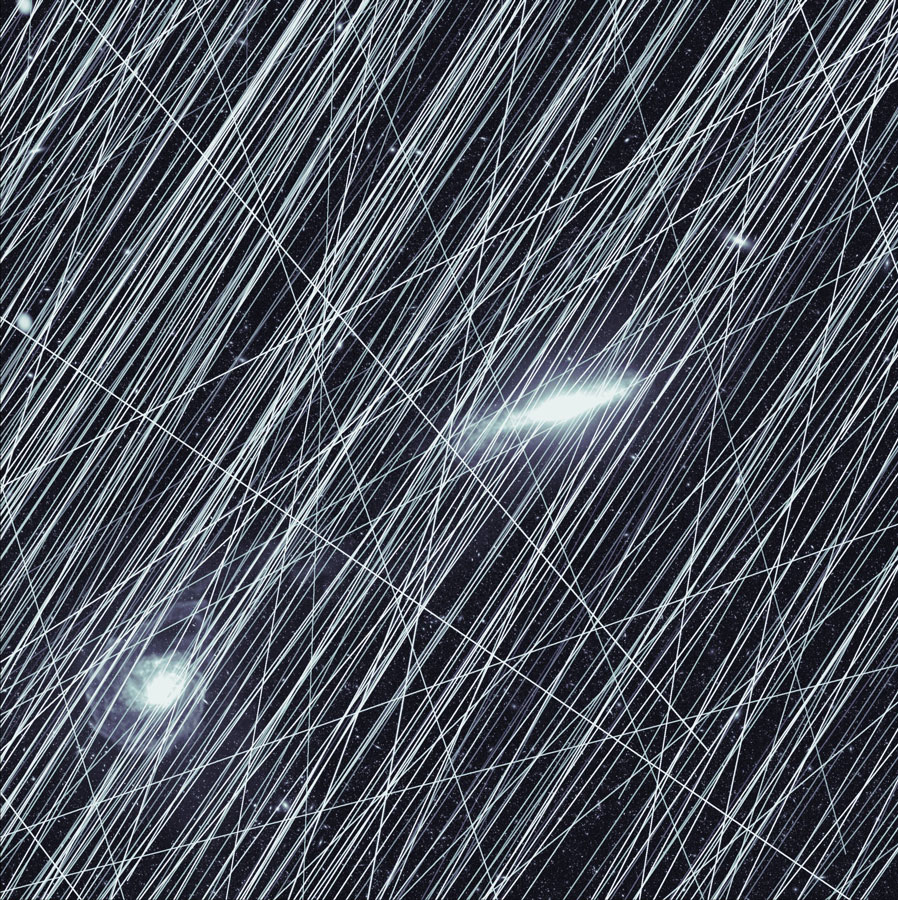

According to one study, more than 95% of images from space telescopes risk being compromised by satellite light trails.

Over the past five years, Earth’s orbit has become unrecognizable. The number of active satellites has grown at an unprecedented rate, transforming the sky. So far the most evident impact has been that of the light trails that appear in astronomical images taken from the ground: they are the reflections of the Sun on moving satellites.

But a new study published on Nature reveals an even more surprising fact: even space telescopes are starting to “suffer” this invasion.

Hubble too. For millennia man has scanned the sky. For less than seventy years, however, we have begun placing instruments directly beyond the atmosphere, concentrating them above all in low Earth orbit, within 2,000 kilometers of the surface. One of the symbols of modern science also orbits in this crowded neighborhood: the Hubble Space Telescope.

For 35 years, Hubble has revolutionized astronomy thanks to its position about 500 km from Earth. But now that same orbit is populated by thousands of satellites, most launched in the last five years.

Orbital traffic. Between 2018 and 2021, 4.3% of its images showed at least one satellite-induced streak. Things have gotten worse: in 2021 there were around 8,000 active satellites, today they exceed 13,000, not counting debris, wreckage and stray components.

To understand how much this “orbital traffic” will interfere with space telescopes, the study simulated several scenarios using a public database of artificial objects in orbit. The simulations range from moderate assumptions – 10,000 satellites – up to an impressive one million, a figure close to the total launch requests already submitted by companies around the world to the International Telecommunications Union.

Simulation. It is unlikely that there really are a million, but according to the authors the most realistic figure for the future is still gigantic: around 560,000 satellites, equal to the sum of the mega-constellations already announced (each made up of over 1,000 units). Using this population as a model, the team took real Hubble images from 2023–2024 and calculated how many times a satellite would cross the field of view at the time of the shot.

The estimate is alarming: with 560,000 satellites in orbit, almost 40% of Hubble images would be contaminated by at least one trail.

The other telescopes involved. Hubble isn’t the only one. It might seem that telescopes further away from Earth – such as the James Webb Space Telescope, which is 1.5 million kilometers away – are safe. It’s partly true. But other observatories, such as NASA’s SPHEREx (launched in 2024 and positioned at 700 km altitude), would be much more exposed: over 96% of its images would include a light trail.

The simulations also include the next low-orbit telescopes: China’s Xuntian, expected in 2026, and the European Space Agency’s ARRAKIHS, expected in 2030. The expected average number of trails per single exposure is impressive: around 2 for Hubble, 6 for SPHEREx, 70 for ARRAKIHS and 90 for Xuntian.

The real damage. To truly evaluate the scientific damage we need to understand how bright these trails are. And this is difficult to estimate: satellites have many reflective surfaces, sunlight hits them from different angles, and they often perform unpredictable maneuvers.

Furthermore, companies rarely share precise information about their designs or the behavior of their vehicles. Despite these limitations, Alejandro S. Borlaff and his team concluded that the brightness of the trails would be much higher than the minimum detectable threshold, therefore inevitably invasive. Satellites do not reflect light only from the direct Sun. Even that reflected from the Earth and the Moon contributes to the contamination: it is weaker, but not negligible. And all of this doesn’t even consider another controversial category: highly reflective satellite designs meant to illuminate urban areas or provide “sunlight on demand.”

What to do. Make satellites dimmer, share precise data about their trajectories, conduct tests and simulations of how they reflect light, and support a global network of observatories to monitor satellite pollution. Borlaff’s working group proposes three additional recommendations for protecting space telescopes:

«Prevention», i.e. placing commercial satellites at lower altitudes than space telescopes to drastically reduce the risk of interference. «Elusion», i.e. creating an open and precise archive of the orbits of all artificial objects, updated in real time. «Correction», i.e. digitally eliminating or reducing the effects of trails in scientific images.

The International Astronomical Union is working on SatChecker, a tool for predicting the passage of satellites. But for space telescopes the data precision must be a few centimeters, not kilometers as is the case today with TLEs (Two-Line Elements). This requires much closer collaboration from commercial operators. And even if all countermeasures were adopted, the night sky would still be profoundly transformed.