![]() An international study led by researchers from Australia’s La Trobe University and the University of Cambridge has challenged the classification of one of the world’s most complete human ancestral fossils, raising the possibility of a new human species. Pictured: Dr. Jesse Martin. Credit: La Trobe University

An international study led by researchers from Australia’s La Trobe University and the University of Cambridge has challenged the classification of one of the world’s most complete human ancestral fossils, raising the possibility of a new human species. Pictured: Dr. Jesse Martin. Credit: La Trobe University

When paleoanthropologists finally freed the skeleton called Little Foot from its stone prison in South Africa, they believed they were meeting an old acquaintance. Instead, they may have uncovered a stranger.

After decades of excavation and debate, a new analysis argues that Little Foot — one of the most complete hominin fossils ever found — does not belong to any known species. If the claim holds, it suggests that early human evolution in southern Africa was even more crowded, and more surprising, than scientists assumed.

“This fossil remains one of the most important discoveries in the hominin record and its true identity is key to understanding our evolutionary past,” said Dr. Jesse Martin of La Trobe University, who led the new study.

A Fossil that Refuses to Fit

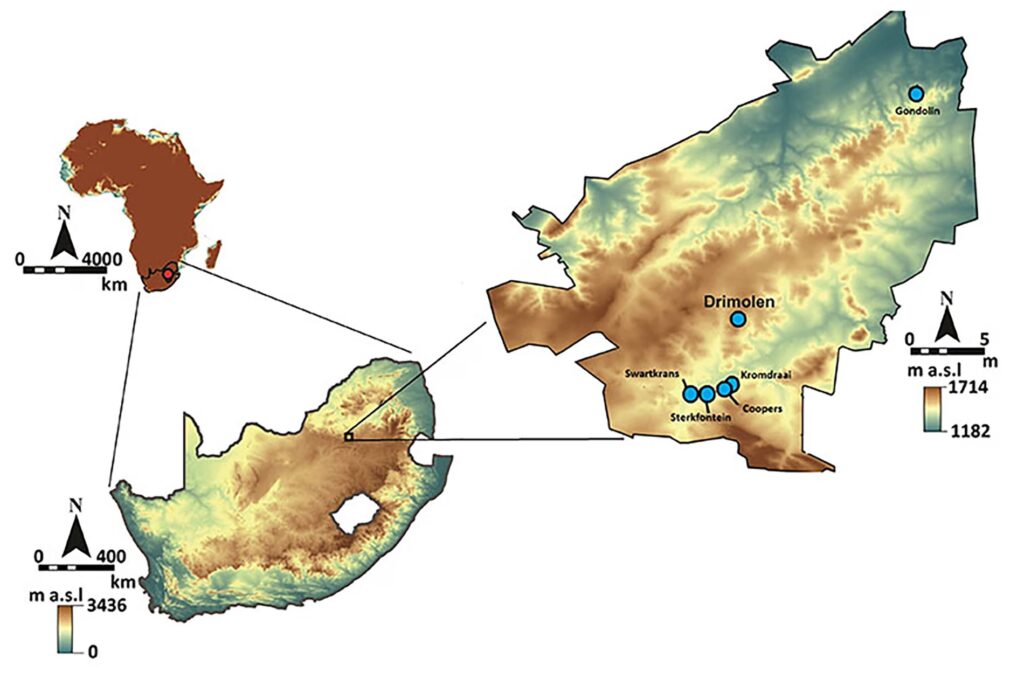

Little Foot, a specimen formally known as StW 573, comes from the Sterkfontein Caves near Johannesburg, a UNESCO World Heritage site often called the “Cradle of Humankind.” The fossil earned its nickname from four tiny ankle bones discovered in the cave in the early 1990s. Those bones eventually led to a spectacular find: an almost complete skeleton embedded in rock.

It took more than 20 years for paleoanthropologist Ronald Clarke and his team to excavate the remains. When the fossil was unveiled in 2017, Clarke argued that it belonged to Australopithecus prometheus, a species name proposed in 1948 by anatomist Raymond Dart for South African fossils he believed were unusually large-brained and behaviorally advanced.

Most paleoanthropologists later rejected that idea, concluding that A. prometheus was not meaningfully different from Australopithecus africanus, the classic species Dart had described in 1925 from the famous Taung Child.

A map of the site where Little Foot was discovered. Credit: La Trobe University

A map of the site where Little Foot was discovered. Credit: La Trobe University

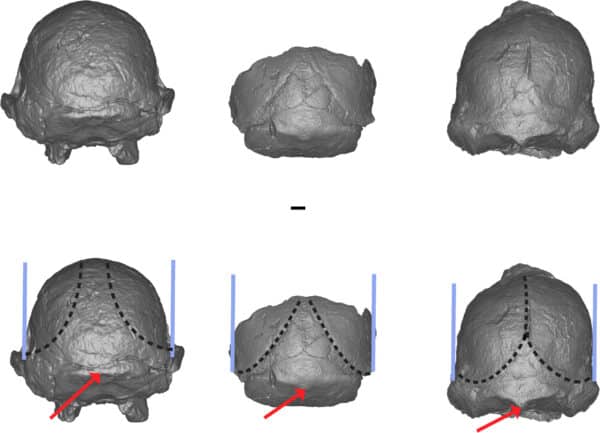

The new study, published in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology, challenges both camps. Martin and his colleagues compared Little Foot’s skull in detail with other fossils from Sterkfontein and Makapansgat. These included the fragmentary skull known as MLD 1 — the type specimen for A. prometheus. Their conclusion was very straightforward.

“We think it’s demonstrably not the case that it’s A. prometheus or A. africanus. This is more likely a previously unidentified, human relative,” Martin said.

Even More Unique

The team focused on a part of the skull that usually changes very slowly over evolutionary time: the back of the cranium, where the head meets the neck. Using high-resolution 3D scans, they documented multiple differences between Little Foot and both proposed species. It shows a longer nuchal plane, a pronounced bump at the back of the skull, and distinct patterns where skull bones join.

“The bottom back of the skull is supposed to be fairly conserved in human evolution,” Martin told The Guardian. “If you find differences between things in the base of the cranium . . . those differences are more likely to represent different species”

The study reminds us that the only fossil ever assigned to A. prometheus looks, anatomically, much more like A. africanus than like Little Foot. That means A. prometheus probably should not exist as a separate species at all, the authors note — a point many researchers have argued for decades — while Little Foot stands apart from both.

3D models of the backs of the skulls of a known A. africanus, MLD 1, and Little Foot. Credit: American Journal of Biological Anthropology, 2025.

3D models of the backs of the skulls of a known A. africanus, MLD 1, and Little Foot. Credit: American Journal of Biological Anthropology, 2025.

A crowded past of hominins

For much of the 20th century, paleoanthropologists assumed that human evolution unfolded as a simple sequence, with one species replacing another in a tidy progression. That view began to fracture in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, as new discoveries piled up. In East Africa, fossils show that Australopithecus afarensis — Lucy’s species — overlapped in time with at least two other hominins. In southern Africa, Australopithecus africanus appears alongside early members of the genus Homo. Farther north, in Eurasia, modern humans later shared the landscape with Neanderthals and Denisovans, sometimes interbreeding with them.

“We think it’s normal for us to be the only ones, but really our situation is aberrant,” Martin said in an interview with IFLScience. “We know from the history of other life forms that being the only survivor of a genus is not a good sign for a species’ survival.”

Sterkfontein itself is revealing in this aspect. Fossils attributed to A. africanus, early members of the genus Homo, and the enigmatic Homo naledi all come from nearby caves, sometimes separated by only a few hundred meters. Adding another species to the mix would reinforce the idea that southern Africa was a long-term experiment in human evolution, with different lineages adapting (sometimes) in parallel to shifting climates and landscapes.

Professor Ron Clarke from Wits University is shown with skull of Little Foot (StW 573). Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Professor Ron Clarke from Wits University is shown with skull of Little Foot (StW 573). Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

The researchers stopped short of formally naming a new species. They argue that the honor should go to Clarke and his collaborators, who spent decades excavating and analyzing the fossil. “It is more appropriate that a new species be named by the research team that has spent more than two decades excavating and analysing the remarkable Little Foot specimen,” the authors wrote in the paper.

Even Little Foot’s age remains unsettled. Some dating methods place the fossil at around 3.7 million years old, while others suggest it could be closer to 2.6 million. That uncertainty makes its place in the human family tree even harder to pin down.

What is clear is that Little Foot no longer fits comfortably into existing categories. Instead of clarifying a tidy evolutionary sequence, it complicates the story — adding another branch where scientists expected a straight line.

As Martin put it to IFLScience, “When it comes to human diversity, specifically in South Africa, the story gets more complex every time you put a trowel in the ground.”

The findings appeared in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology.