In a world first, scientists in Germany have successfully recorded tiny oil droplets hovering within a flowing liquid, and even drifting upstream against the current, defying typical fluid behavior.

Captured under a microscope by a research team at the Technical University of Darmstadt (TU Darmstadt) in Germany, the oil droplets’ striking behavior points to a previously unknown fluid phenomenon.

The scientists, led by Steffen Bisswanger, a PhD candidate at TU Darmstadt and head author of the study, believe that the discovery may be particularly relevant for process engineering, analytical chemistry and microfluidic applications.

“The phenomenon of droplets being held in place or even moving upstream was previously unknown and has now been documented and explained for the first time,” Bisswanger explained.

A surprising phenomenon

For the study, the researchers relied on the Ouzo effect to create oil droplets for a laboratory experiment. The Ouzo Effect is the clouding that occurs when water is added to anise-flavored spirits.

The phenomenon causes essential oils to create tiny droplets that turn the drink milky white without added surfactants. By injecting an alcohol-oil mixture into water inside a narrow flow channel, the team generated microscopic oil droplets.

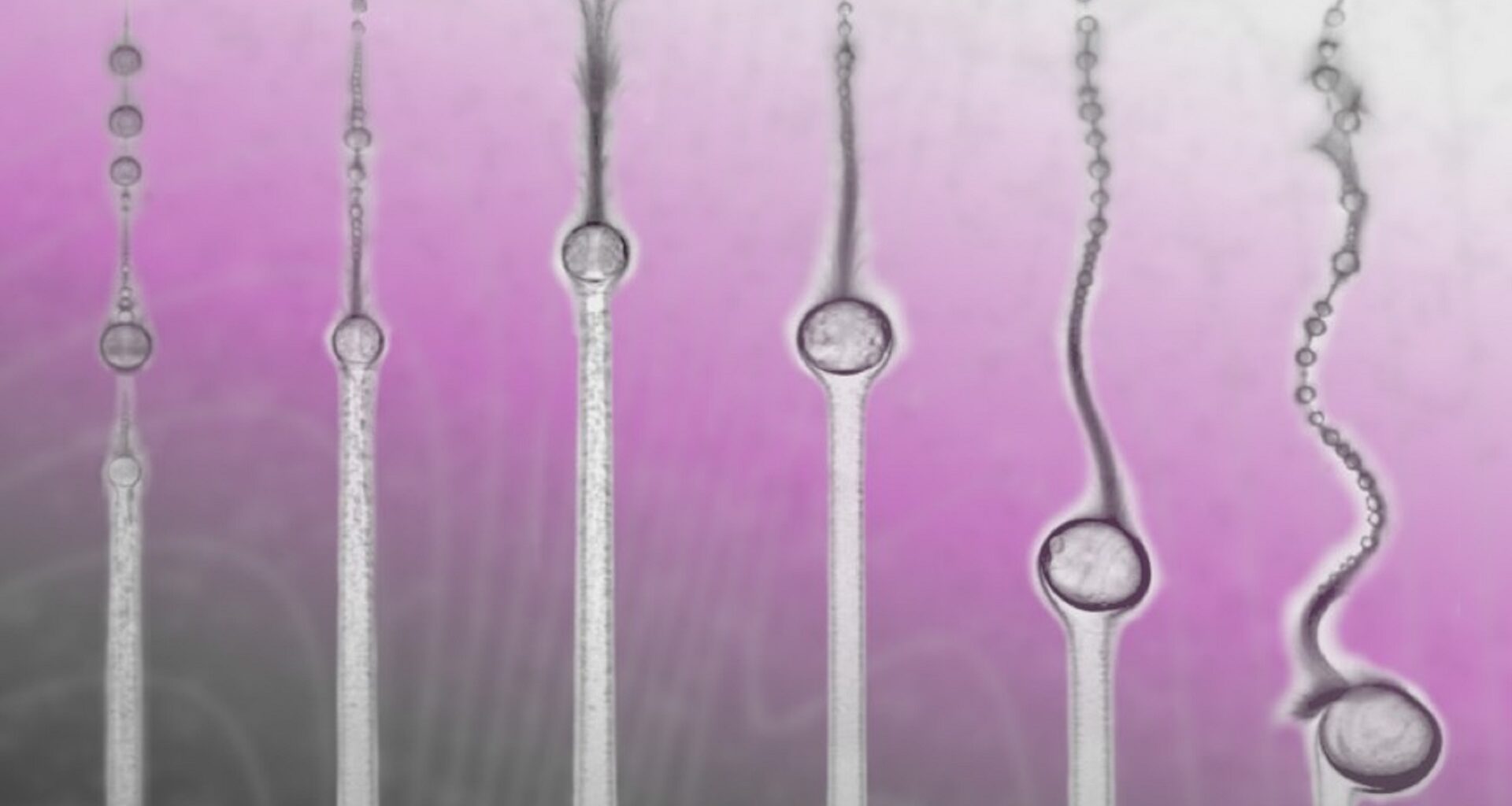

They then used high-speed cameras to observe how the droplets behaved under flowing conditions and found that they could resist the flow, remain stationary, or even move upstream.

“The force that holds the droplet in place results from a difference in surface tension at its upper and lower ends,” Bisswanger elaborated in a press release.

He explained that the equilibrium allowing the droplet to hover depends on its size and position, as well as the flow rate and the type of liquid moving through the channel.

“A general conclusion is that Marangoni stresses can reverse the motion of droplets through channels, where the surrounding liquid is a multi-component mixture,” the researchers said.

Unexpected flow dynamics

Although the phenomenon can only be observed at microscopic scales and under carefully controlled experimental conditions, its impact could extend beyond lab settings.

According to the researchers, the effect could also become visible at larger scales, such as in emulsions, liquids in which countless tiny oil droplets are distributed in water.

Steffen Hardt, PhD, a professor of nano- and microfluidics at TU Darmstadt, noted that in such systems the observed effect could take place billions of times at once in a single container, and potentially lead to the formation of complex patterns.

“The phenomenon we observed and described could also be used to extract tiny droplets or bubbles from a liquid for analysis,” Hardt concluded. The project was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

The discovery could also open new possibilities in analytical chemistry. The team suggested the effect could be used to selectively trap or extract tiny droplets or bubbles from flowing liquids, a potentially useful tool for lab-on-a-chip systems, chemical analysis and diagnostics.

The results have been pre-published online in the journal Soft Matter. The issue is expected to follow at the end of January 2026.