If you look at pro racer’s bikes or ads in magazines (ours included) the future of drivetrains look to be headed in a very battery-powered direction. But when I look at my local trailhead the reality is a little different. Sure, there are some wireless bikes. But there are still a lot more good old mechanical derailleurs heading out onto the trails.

That had me thinking: what if the future of drivetrains isn’t wireless? Or, more specifically, what if it isn’t just wireless? So I talked to three small, but growing brands pioneering a new space for mechanical drivetrains. All three look very different than your usual, mass-produced derailleur. All three are repairable and, to greater or lesser extents, broadly compatible. And all three boutique derailleurs are mechanical. Crucially, all three see space for a derailleur that is just wireless.

The players: A veteran, the tinkerers and a fresh face

The three derailleurs on the table today are Vivo’s Enduro II, Madrone’s new Jab and Ratio’s simply titled Mech.

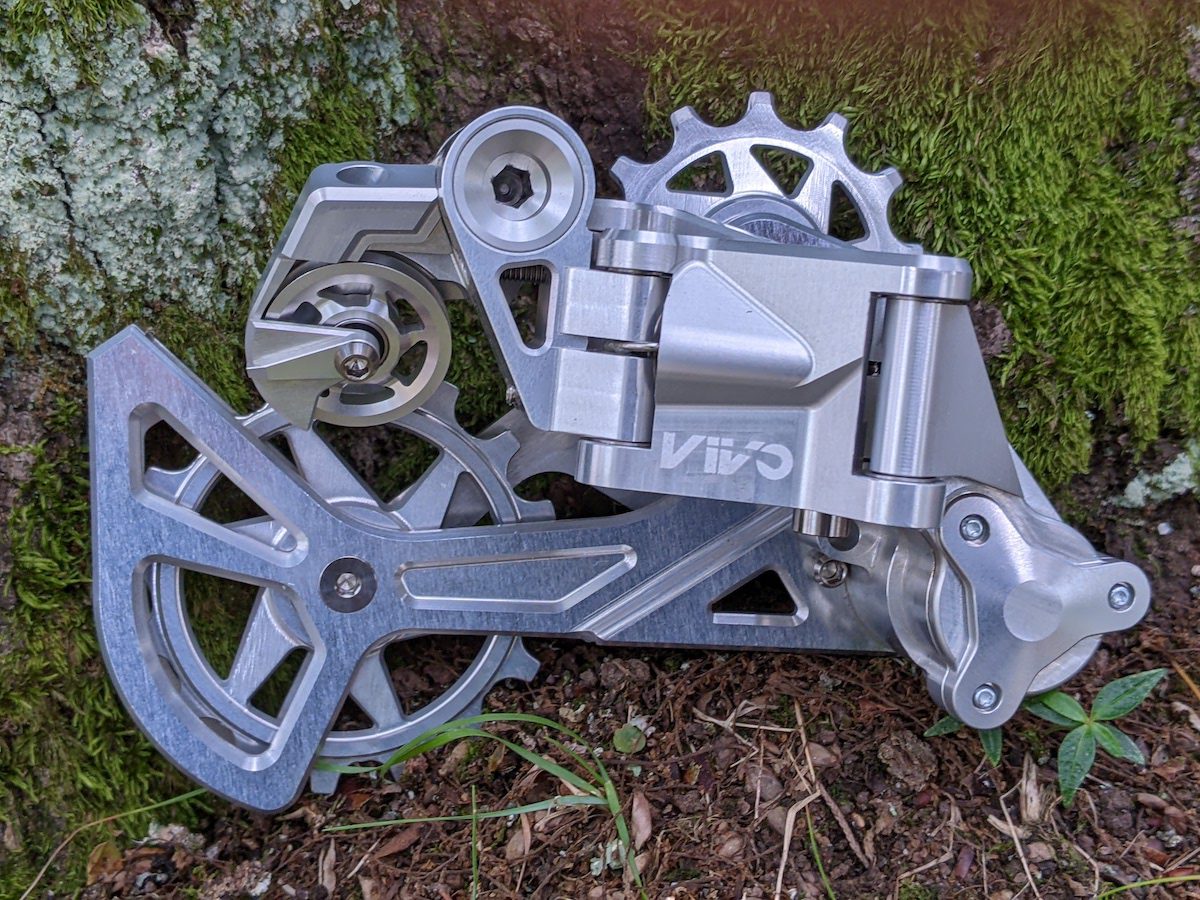

Vivo Artisan is run by John Calendrille, bringing 30 years of experience designing derailleurs, mechanical and electric, for numerous major brands as well as under his own brand. Enduro II, and its companion F3 shifter, are assembled by hand in New York, numbered, and fully rebuildable.

On the other side of the pond, Ratio Technology launched the Mech off the back of more than five years of offering upgrade kits for derailleurs and shifters, mostly SRAM, as well as a some other small components. The Mech covers a broad range of uses and compatibility using a modular design and is manufactured entirely in the U.K., mostly by Ratio in the Lakes District.

Back in the U.S.A., Oregon-based Madrone quickly launched from offering SRAM repair kits in 2023 to launching the Jab, it’s broadly compatible derailleur. While the Jab is one derailleur, there are multiple configurations to cover a wide range of compatibility (and colours) from gravel to mountain bike and some weird spaces in between.

Why take on the drivetrain giants?

From the outside, taking on the giants of drivetrain manufacturing seems like signing up for some mix of a David and Goliath style battle, and a wildly complex technical challenge. But all three brands have found and opened up a similar space for their own creations. It should be noted that Italy’s Ingrid Components has also played a roll, if a slightly different one, in opening up this space for high-end boutique derailleurs.

The final form of each derailleur reflects the initial driving motivation of each brand.

Vivo’s wish list

“I wanted to design my own part without any compromises, without any restrictions. Just total freedom to create what I wanted,” says Calendrille. “When you design for other people, you come up with your dream product and they want to change this, they want to change that,” the Vivo founder says, adding that the need to design for mass production requires some form of compromise, and often a shift to permanence over an ability to repair.

From his years designing for others, Calendrille had a laundry list of features he wanted to incorporate into the Enduro II that challenge the disposability of a mass-produced, difficult to repair derailleur.

“I wanted a derailleur that’s rebuildable, super robust, using the best materials like 7075 aluminium and titanium. I wanted cartridge bearings at the pivot points. A robust clutch mechanism. Oversized pulleys.”

Madrone turns lemons into lessons

In Oregon, Aaron Bland ended up creating one of the more brightly coloured derailleurs out of frustration. Madrone started with repair kits for SRAM AXS derailleurs and, at some point, Bland realised they learned so much about what wasn’t working that they ended up knowing how to make one that does work.

“There wasn’t an intention to make derailleurs,” Bland says. “So we were well versed in these weak points and failures. It was just more and more clear that, if we can make all the parts, we can take care of customers completely and we control our own destiny. It just seemed natural.”

Bland adds that the major player’s myopic focus on electronics also opened up space for Madrone on two fronts.

“SRAM and Shimano have kind of moved beyond continuing to refine the mechanical derailleur. So it leaves this opening for us to come in and really deliver something that, well, our goal is to make the world’s best mechanical derailleur,” Bland explains, adding that, with mechanical shifting, “The reliability is kind of hard to deny. There’s a certain reliability that you just can’t achieve with electronics.”

An uncharacteristically sunny day for shooting the Ratio Mech

An uncharacteristically sunny day for shooting the Ratio Mech

Ratio weathers the storm

For Ratio, based in the wet U.K. Lakes District, choosing mechanical over electronics was a simple product of their environment.

“We ended up struggling quite a lot with those SRAM derailleurs getting exposed to water and salt in the winter and just going bad. So we don’t necessarily think electronic is the answer,” says Tom Simpson, co-founder of Ratio. “So the brief was to make a mechanical derailleur that was as accurate and repeatable as electronic, but with the serviceability that comes with it being mechanical. Making all the replacement parts and making it so you can take it apart easily.”

Along the way, Ratio’s added simple features to demystify the rear derailleur and make it easier for us end users to keep it running smoothly.

“We do appeal to the nerdier sort of cyclists, but all the same it’s a massive underestimate. People are much more capable than you might first assume, particularly if you give them certain support,” Simpson explains.

He thinks that helping riders understand their bikes better can counter the perception that electronic systems are simpler.

“All you need to do is explain which direction they turn the little adjuster and, lo and behold, it’ll work perfectly and they’ll be totally happy.”

A Vivo Enduro II, in pieces

A Vivo Enduro II, in pieces

Right to repair versus a black-box

One common theme from all three is that a high-end, expensive part should not be disposable. If riders are going to invest in an expensive derailleur, it should be repairable. It should last, like a set of fancy hubs, for years. If a hub can travel from bike to bike, why not a derailleur?

Calendrille, who has experience designing for mass production, says he can understand why most derailleurs end up the way they do.

“The major brands, they’re making 10s of 1000s of units. When you put something like that into production you have to change the way the parts are manufactured and then assembled in a permanent fashion. That is quick and cost efficient. They’re not prioritising a rebuildable product. It’s more like a disposable product.”

With the move to electronics, Bland says, “People are getting fed up with planned obsolescence and the throwaway derailleur. Not only is it a throwaway, high cost item. It’s also e-waste, which is a real bummer. That’s the worst thing for a landfill.”

While disposability is the byproduct of simplicity (“pins get riveted because thats the fastest and most reliable way for a robot to smush metal down and hold it in place”), Bland explains that low product volume gives them more freedom.

“It’s actually kind of easy to design for repairability,” the Bland argues, adding that Madrone is part of the right to repair movement. “That ethos is part of how we want to create products and support them.”

Madrone is even offering a refurbish program where, if you don’t want to repair your Jab or wait for it to be repaired, you can sell it back to Madrone to offset the cost of buying a new (or new refurbished) one. The goal is to create a circular supply chain where as little is thrown out as possible.

Ratio Mech is broadly compatible. It’s also designed to be easy to understand and use as possible. Like a barrel adjuster that shows you which way to turn it to move the derailleur the direction you need.

Ratio Mech is broadly compatible. It’s also designed to be easy to understand and use as possible. Like a barrel adjuster that shows you which way to turn it to move the derailleur the direction you need.

Tearing down the walls of compatibility

Ratio and Madrone are challenging another convention wisdom, one major brands have spent years teaching us: That drivetrains should be walled gardens of compatibility.

Will Weatherill is an engineer at Ratio, whose simply titled Mech, in their words, “rails against” brands dictating narrow compatibility.”I think the classic example was when, and SRAM and Shimano both did it, when they went from 11 speed electronic to 12 speed electronic, and you weren’t allowed to use your shifters anymore. It’s a little bit insulting, isn’t it? You’re telling me that you can’t get those old shifters to talk to that new derailleur?”

Both the Jab and Mech are already broadly compatible. Across 11, 12 and, for Mech, 13-speeds. Across brands, even mixing brands. In part, that addresses riders frustration that their “old” parts are considered useless once something new comes out.

“Our whole ethos is that the parts that you have, there’s nothing fundamentally wrong with them,” Simpson says. “As long as you can keep updating the wear parts. There are big draws to updating cassettes with better shifting and a new chain.”

Weatherill adds that Ratio doesn’t want this to be a half-measure to keep parts out of the bin. “We’re happy that the Mech doesn’t compromise performance in any particular set up. That it really is compatible and we’re not just bodging it.”

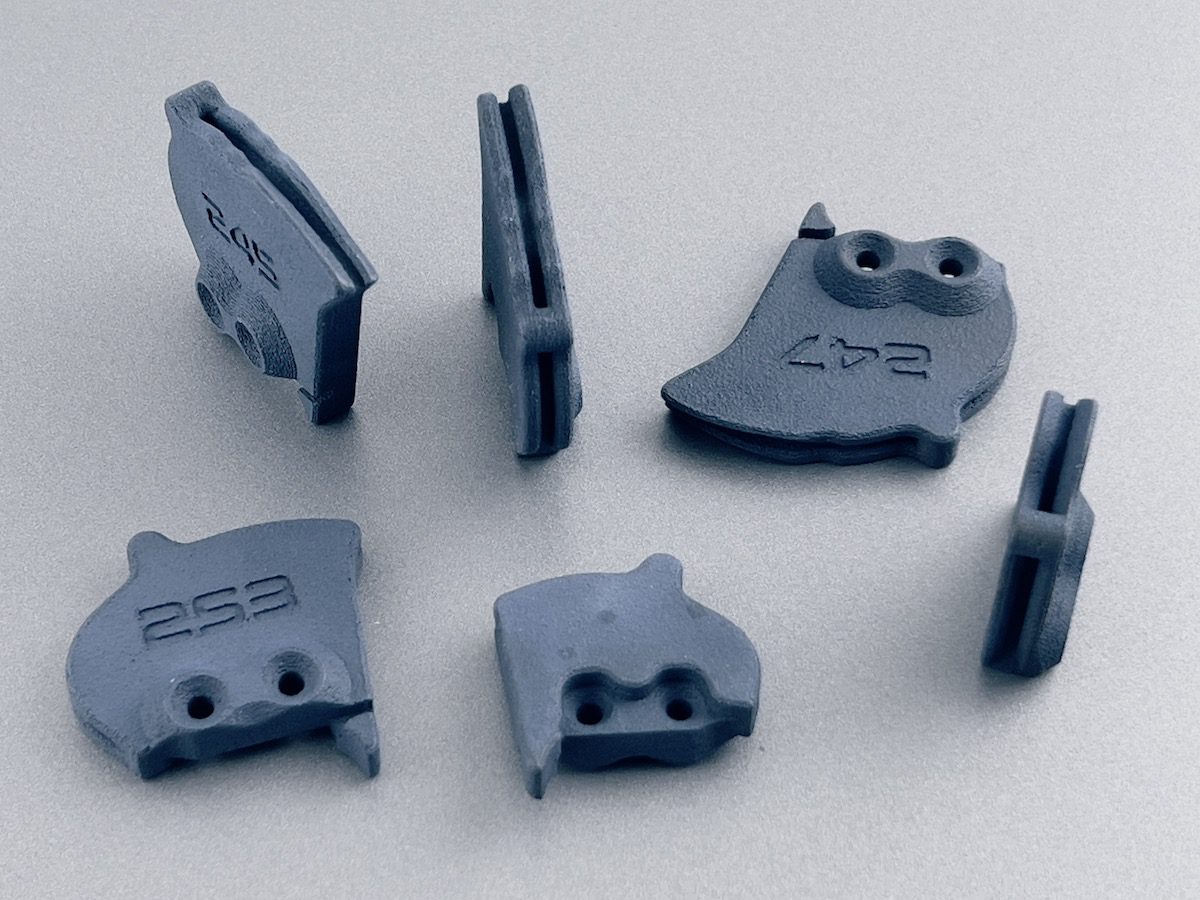

Madrone fins for different pull ratios and compatibility

Madrone fins for different pull ratios and compatibility

Future-proofing as a guard against disposability

Part of the challenge of compatibility and disposability is that you can’t know what comes next. People will only want to invest in buying, maintaining and repairing a boutique derailleur if they’ll still be able to use it when the next cool thing comes out. That mean’s being compatible with new shifter combinations and new cassettes, even new numbers of sprockets.

Both Ratio and Madrone take a similar approach to future-proofing, almost as a bi-product of compatibility. One of Ratio’s earlier products was an upgrade to the fin on SRAM derailleurs that guides the cable from the housing to the B-knuckle. They realised that by changing the fin shape they could adjust the cable pull ratio and make, say, a SRAM derailleur work with Shimano shifters.

More importantly, I’d argue, is that this allows both brands to continue developing fins to work with more drivetrains, both existing and yet-to-be-released. Ratio even sells an upgrade kit to turn 11-speed SRAM road shifters into 12-speed shifters, and another to go from 12- to 13-speeds.

Vivo Enduro II on a very nice Unno

Vivo Enduro II on a very nice Unno

Back to the future of boutique drivetrains

This trio of new derailleurs opens, or re-opens a space for boutique parts that was closed for a couple of decades by the major brands. Back in the 90s, resplendent anodised and CNC’d parts hung off bikes with pride. What caused those alternatives to disappear?

“The perception is that Shimano just kind of crushed everyone when they came out with the latest generation of XTR,” Calendrille recalls. “Shimano puts out a phenomenal product, and they put out a great product in the 90s with that XTR, and that just kind of put a damper on those early CNC derailleurs.”

Since then, the wide availability of 3D modelling, advancements in CNC machining and 3D printing have helped re-open a space for outside players to be competitive.

“That’s all helped make it feasible for little guys like myself and the other guys out there to create a complex product,” Calendrille explains, adding that his ambitions are necessarily to challenge the giants head-on. “Making something that’s better than Shimano is really difficult. I don’t even know if you can get there. As far as manufacturing, they’re just so advanced with the materials and the processes.”

So why are more brands like Vivo, Ratio, Madrone and Ingrid popping up?

“I think there’s just a lot of crazy people like myself that love bike parts so much that they want to create a derailleur from scratch. Which is a hard and crazy thing to do but, for people that love parts like myself, that’s what we do,” says Calendrille. He adds that the other half of the equation, demand, is also returning.

“I also think that in the marketplace a lot of consumers are looking for something different. They’re looking for something that’s not made by the 1000s. Something rebuildable, something super high quality.”

Bits of Madrone’s very modular Jab

Bits of Madrone’s very modular Jab

Is the future of shifting mechanical?

After talking to all three brands, I think that the future of shifting should be at least partially mechanical. Electronic shifting does have a place, and does have loyal fans. But it shouldn’t be the only option. All three of these boutique builders are creating product worthy of high-end bikes. They’re just cable driven, not battery powered.

Let me clarify something. When I saw “boutique,” all three of these are, despite their intricate construction and small production numbers, are less expensive than your average, even cheap wireless derailleur. All three are notable for being beautiful. That all three are beautiful and functional is, to me, more important. And all three are incredibly repairable and, as mentioned, stunningly machined.

Which brings me to the final point. At that price, they are repairable. They can be upgraded to work with future bikes. For less than a wireless derailleur, they are not disposable.

Above all else, before preferences for batteries or cables, I hope these drive the future of shifting by proving that derailleurs don’t have to be disposable. That they can be repairable, modular and adaptable. That three are notable for being beautiful is one thing. That all three are beautiful and functional is, to me, more important.