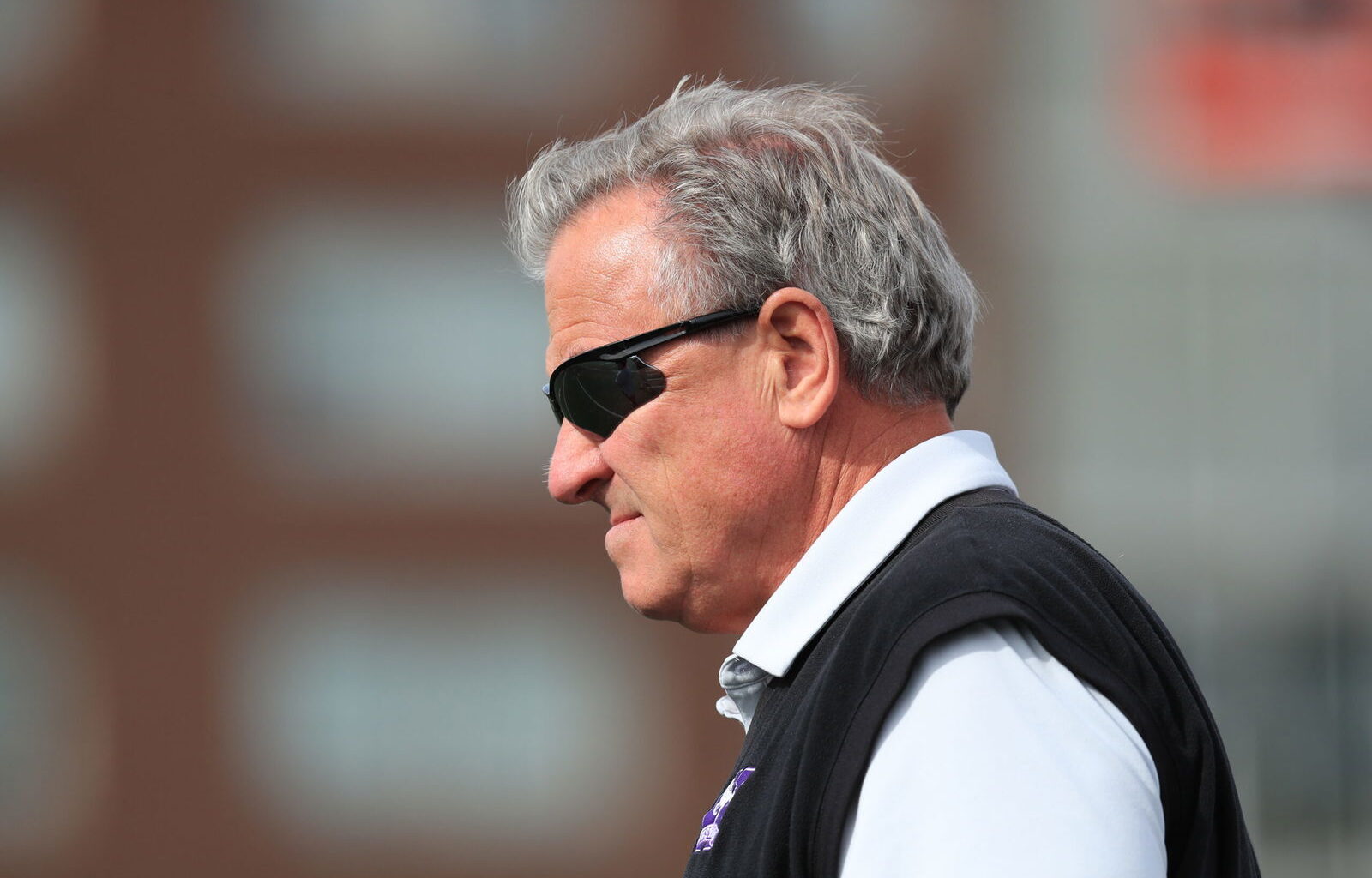

Photo: Bob Butrym/3DownNation. All rights reserved.

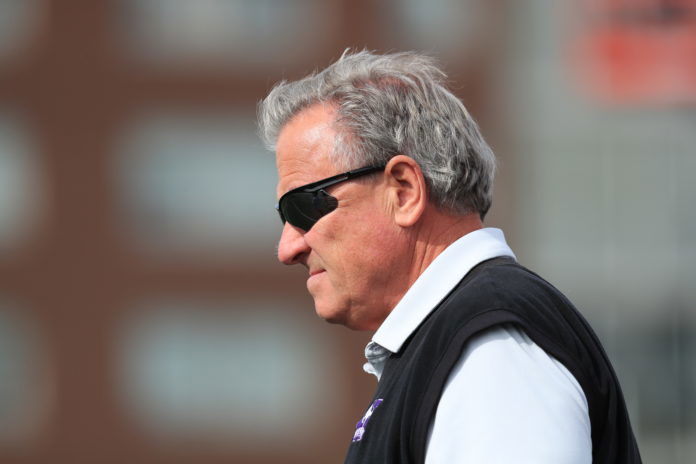

Photo: Bob Butrym/3DownNation. All rights reserved.

Greg Marshall may be retiring as the Western Mustangs’ head football coach, but don’t confuse his departure with disillusionment.

Despite mounting financial challenges across the post-secondary education landscape, the 66-year-old believes that university athletics remains on solid footing in Canada.

“I think we’ll get through this period,” Marshall said. “The funding (challenges), a lot of it’s coming from the change over and the lack of the number of international students that we’re now allowed to bring onto campus. It’s impacting our community colleges, impacting the university, and the first things that are going to get cut are the ancillary services like athletics. We have to find ways around that.”

Cuts to athletic departments across the country have become a looming threat in recent years. Last month, McGill University in Montreal made the most radical decision yet, announcing it would cease operation of 25 different sports next year due to concerns over financial sustainability.

While football was not one of the sports affected, Marshall believes the loss of any program is a blow to the university experience as a whole.

“There are different sports that have different competitive levels. We try to provide a great student-athlete experience for our football athletes. If we think that that student-athlete experience is good, why wouldn’t we try to have that for as many students as possible?” he said.

“I’m not saying that you’re going to fund every program the same. There are some programs that are going to need more funding, but if you can provide that for your football student-athletes, wouldn’t that be good for track and field? And for Ultimate Frisbee, and for other sports, to have as many students who are at your university have that really neat student-athlete experience? Some schools will say, ‘Well, we’re just going to focus on these sports,’ then you’re limiting the experience to just a few.”

McGill’s announcement was met with fear that it could be a canary in the coal mine for other schools. In Ontario alone, nearly half of all universities have been operating at a deficit in recent years, including notable institutions like Waterloo, Queen’s, Wilfrid Laurier, and Guelph. All have made cuts to other aspects of campus life as a result, with athletics providing an easy scapegoat if further trimming is needed.

Football remains U Sports’ most high-profile sport, but it is also the most expensive endeavour for most schools. In 2023, Simon Fraser University in British Columbia axed its NCAA football program, drawing a national outcry. However, the fervour has since died away, and that decision sets a dramatic precedent for any school tired of experiencing a lack of both on-field and financial success.

Western is better positioned than most to avoid any cuts as a perennial powerhouse at a reasonably financially stable school. However, much of the team’s success is still reliant on outside funding, as they attempt to maintain the standard of excellence shared by other top programs.

“A big part of my job is fundraising. We need to go out and secure donors and support to make sure that we keep our football program strong,” Marshall explained. “A school like Laval has kind of set the bar and changed university sport and made it so you better be willing to hire coaches and be able to provide athletic awards to your student-athletes in order to compete with the best schools across the country.”

The costs to keep up in that arms race are only growing, and external factors could soon dump more expenses at the door of football programs across the country. After the Canadian Football League announced that it will make radical changes to its field dimensions beginning in 2027, U Sports has said it will engage stakeholders to decide whether to follow suit.

While the university game is under no obligation to mirror the professional one, moving the goal posts and shortening the field could ease logistical challenges for the schools that share facilities. Marshall is generally in favour of the CFL’s new rules, but acknowledges that implementing them could be a lot to ask for the schools that don’t have professional roommates.

“The one thing I will say is that with university sports, it costs money to move goal posts, so that might take a while. They might sit back and wait and see how it plays out in the CFL before the universities agree to spend the money to move the goal post back and change,” he said.

“Changing from 110 to 100 (yards), that one doesn’t make any sense to me. 10 yards is just not going to create that much difference in offence, and all it’s going to do is create expenses, because all of our fields, most of them have sewn-in lines. I didn’t see much in that one, but I do really like a lot of the other rules.”

Marshall has coached collegiately since 1984, save for a three-year stop with the Hamilton Tiger-Cats. He also won the Hec Crighton Trophy as a running back with Western during his playing days. He marvels at the modern player, noting that these changes and challenges come at a time when U Sports athletes are reaching new heights on the field.

“I think there’s been that natural progression over 40 years. The training techniques, the preparation, how they are coached in minor football and high school football — we’re just seeing better athletes,” he explained. “Not that I didn’t think that I was pretty good in my day and that I could still play now, but the reality is that the players are getting bigger and stronger and faster and more athletic and understand the game more. The game has evolved. It’s certainly more complicated and cerebral than it was 40 years ago.”

As a result, modern players are demanding more from their university experience. South of the border, players in the NCAA are now able to profit off their name, image, and likeness, while the introduction of the transfer portal has sparked unprecedented player movement. While U Sports hasn’t been professionalized to nearly the same extent, the organization recently relaxed its own transfer policy to match the culture shift in amateur athletics.

Some coaches have struggled to adapt to this generation of players, falling out of alignment with students who have a greater understanding of their worth. Even as he steps away, Marshall doesn’t appear to harbour any of that resentment and savours the relationships he’s built with players of every era.

“Yes, everyone’s changed, but I see in our athletes not a huge difference from what it was back when I played,” he said. “They’ve changed, but they’re still motivated. They’re still academically motivated, athletically motivated. They want to do well.”

“The one common thing in coaching throughout my whole time is that I got to coach and interact with some amazing young men. You see that transformation when they come in as 17- or 18-year-old boys, and they’re a little nervous, they’re a little afraid, they’re intimidated, and then to see them grow and develop into young men. And then into fathers and husbands and all those other great things, and go on to be doctors and lawyers and teachers and all sorts of careers. That’s pretty rewarding at times.”

It is that development that makes sports valuable beyond the dollars that schools pour into their programs. Despite modern challenges, he sees a future for Canadian university athletics that is as strong as ever.

“I still believe that what we do in the experience that our students have playing varsity sports is absolutely worthwhile,” Marshall said. “We’re creating some really great people by exposing them to university volleyball, university football, and university basketball, all those sports.”