Is Europe in decline? 2025 was certainly a rough year. Europe is divided and struggling to concert its position both on financial support for Ukraine and trade policy (Mercosur). On trade policy and energy, the EU accepted a humiliating beating by Trump. Given the Russia threat, the weakness of Europe’s defenses leave it little option but to try to stay in Trump’s good graces.

The story on the American economy, including AI, has soured over the course of 2025. But here too the sense of Euromalaise persists, with the German economy locked in polygloom and storm clouds gathering over France’s public finances. All of this adds to the questions posed in the summer of 2024 by the publication of the Draghi report, which crystallized, amplified and legitimized European Angst.

Adam Tooze is a distinguished, prolific historian — I think I was introduced to him by The Wages of Destruction, about the German economy during World War II — who has also been a leader in the newsletter/Substack revolution. His Chartbook is essential reading. Given some of his recent writing about Germany, plus Trump’s declaration that Europe is effec…

Read more

8 days ago · 918 likes · 228 comments · Paul Krugman

It is really the long-run perspective of the Draghi report to which we owe the “decline” meme. The report warned of a European economy that is falling behind in key sectors due to a lack of investment in R&D. Draghi, as the strategic representative of European capital that he is, made the case for a European version of “state-capitalism” light. Put the politics, the geopolitics and the economics together and you have the makings of a deep funk. So much so, that the funk itself demands attention.

Some are not buying it. Most notably Gabriel Zucman in Le Monde, who insists: ‘The idea of a sclerotic Europe facing an American El Dorado has little basis in fact’. Thomas Piketty backed him up, demanding “Il faut sortir de l’auto-dénigrement” – we must leave self-denigration behind!

Zucman and Piketty insist that the funk is so deep that Europe can’t see straight any more. According to their data, labour productivity per hour is actually higher in Europe than in the US.

This is an eye-catching claim which, as far as I am able to establish, depends on your data source. As Zucman’s piece makes clear he is basing his claim on data from the International Labour Office (ILO):

According to statistics from the International Labour Organization, GDP per hour worked, the standard measure of productivity, is $81.80 in the US, $83 in Western Europe and $71.10 across the EU. And there is little sign of European “sclerosis”: Over the past 30 years, productivity has increased at roughly the same pace in Europe as it has in North America.

These do indeed show that output per hour worked – the best measure of labour productivity – in the most advanced parts of Western Europe has been consistently above that in the US. This means that higher US output per worker and overall GDP are explained by longer working hours and greater growth in the employed population. No European decline, therefore. Simply different choices about work-life balance and labour force.

However, if you look at other data sources you get a different story. If you go to the OECD database on hourly labour productivity or the AMECO data base (that Draghi and the ECB use) the US-European productivity gap looks less dramatic than the public narrative might suggest, but nevertheless real.

Source: OECD

The difference between the ILO, OECD and AMECO data would seem to be explained by the numbers for labour input. If you count relatively higher labour input you end up with relatively lower output per hour.

Let us say, for sake of argument, that Europe’s technocratic elite are not simply talking their own book and cooking up a crisis. Let us assume that the OECD-AMECO data used by the majority of economic research are showing us something real, then the situation looks like the one described here by the Banque de France. In productivity per hour worked Europe is diverging from the US in the wrong direction and making up for it by working longer (A story we also see in the UK).

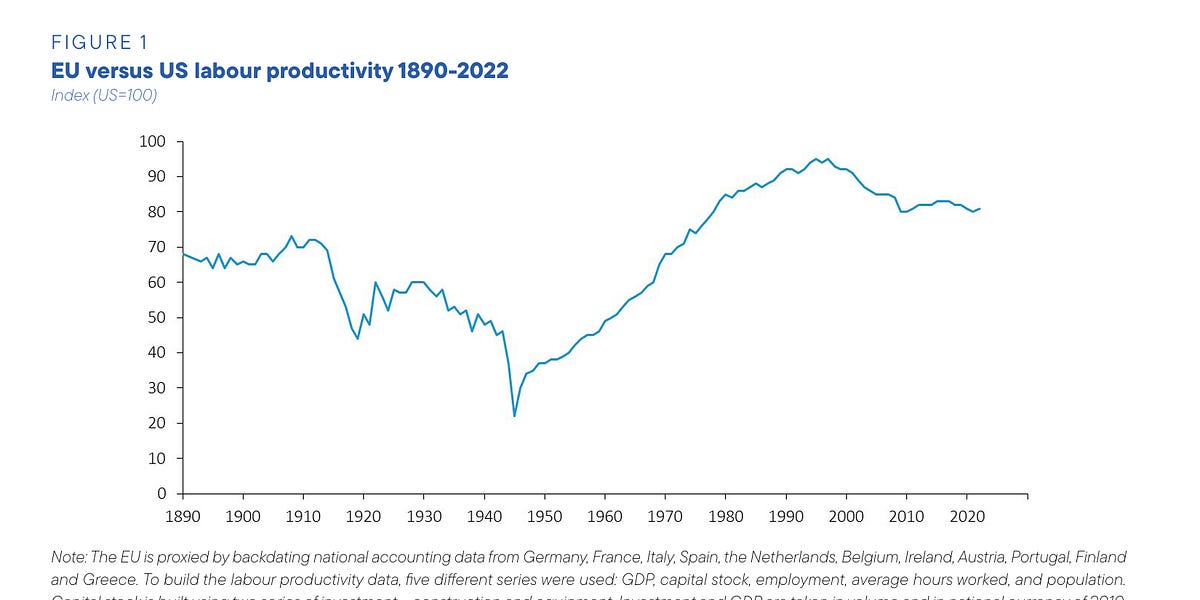

But granted there is downward divergence, one question you might ask is whether “decline” is really the proper term to describe the graph at the heart of the Draghi report. If we go back to the Draghi report the key image is the one below. This is the basis for the “declinist” view.

Is “decline” the right word to describe what we see here? I would say, not. Decline implies some kind of persistent movement in a downward direction. That is not what we see, even over the long run.

Up to the 2000s there was a period of convergence. This was followed by a period in which the US reasserted a significant lead. But that was too short to constitute decline. Furthermore, Europe’s economies were actually growing fast in the 2000s. From the 2010s, the gap leveled out and we have now been living with it for 15 years without much further deterioration. Perhaps, the real message is that we are on the brink of a cliff and decline is about to set in hard. But that is a future projection rather than a current diagnosis.

Beyond labour productivity per hour a further question we might ask, is how far labour productivity differences are explained by greater levels of investment in the US. With more capital per worker you would expect higher productivity. But that does not come for free. It involves depriving yourself of consumer goods to “make room” for investment. So the real measure of economic performance is so-called Total Factor or Multi-Factor Productivity. If Europe has not been working much or investing much that too is part of the social bargain and may be an acceptable bargain so long as Total Factor Productivity remains high – call it “slouching towards Utopia” (Brad de Long)

Source: António Dias da Silva, Paola Di Casola, Ramon Gomez-Salvador and Matthias Mohr, ECB.

But on TFP measures too the picture does not look rosy for Europe. Clearly a substantial difference built up between Europe and the US driven both by “doing things better” and greater levels of investment. But again, this has been a persistent gap over more than 15 years (I will come back to the COVID experience below).

So something real is going on, though it may not fit well with a decline emplotment. And we can go further than that: If we dig a bit further into the data there is a wide measure of agreement that difference in the national averages is driven by the outperformance of super star firms above all in the tech sector. America’s most highly rated big firms (above all in tech) are head and shoulders above all their competitors, whether European or American, in terms of innovation and R&D investment.

Source: Oyun Erdene Adilbish et al, IMF.

It is not the US economy as a whole that is outperforming Europe, but its leading tech firms.

Source: Banque de France

But the corollary of that finding is the reality we all observe, which is that if you are not in that favored, dynamic and rapidly growing upleg of America’s K-shaped economy, things are distinctly uncomfortable and you might actually prefer the European social bargain – even the European social bargain in its current frayed and dilapidated form.

To drive this point home, consider the recent past: the COVID shock.

Between 2019 and 2024 productivity between the US and Europe diverged again quite sharply, first during the pandemic itself and then with the impact of the Ukraine war after 2022. This has, no doubt, added to the current EU funk. The last few years have been rotten.

But is this surprising? The US “labour market policy” consisted in 2020 of letting unemployment rip and then handing out cash checks. Unsurprisingly, labour productivity surged. By contrast, the Europeans spent huge quantities of money in supporting short-time working schemes that are, in effect, officially underwritten low productivity. Remember this?

Source: Washington Post

So perhaps the best way to think of the comparison is to abandon the stark separation into European v. US economy and to see the US superstar tech firms on the one side, call it California, and Europe and the rest of the US economy perched more or less comfortably on the downleg of a K-shaped OECD economic bloc.