Arash Darbandi, a photographer from Ahvaz in southwestern Iran, told the Ukrainian outlet that he arrived in St. Petersburg on a tourist visa and supported himself by taking photographs of passersby.

“I took photos of anyone who was dressed in colorful clothes. If they liked the photo, they paid me 1,000 rubles ($10-11),” he said.

Although trained as a petroleum engineer, Darbandi said photography had been his main livelihood.

He acknowledged knowing that Russia was at war with Ukraine but said the conflict initially felt distant. That changed after an encounter with police that led to his detention.

According to Darbandi, he was arrested following an altercation with a police officer and taken to a military facility on Ligovsky Prospekt.

He said authorities gave him a stark ultimatum: prison or the battlefield.

“They told me that I either had to go to prison for three to five years, or go to the war for one year,” he said.

When he objected and argued that deportation should be the maximum punishment for a foreigner, he said officers replied: “This is Russia, and you must go to war.”

Iran emerged as one of Russia’s key military backers since Moscow launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Tehran has been accused of supplying Russia with hundreds of Shahed-series attack drones, which have been widely used against Ukrainian cities and infrastructure.

Western governments and Kyiv say Iranian-made drones have played a central role in Russia’s aerial campaign, a charge Iran has repeatedly denied or downplayed.

Self-harm to avoid war

Darbandi said he was held in barracks for months before being sent to a training center near Belgorod.

Fearing deployment, he said he deliberately injured himself, breaking his arm, but was still not exempted from service despite Russian law.

“I had never even held a knife,” he said, stressing he had no military background.

He described training as minimal and coercive, saying recruits were treated as expendable.

“They didn’t treat us as humans; they only saw us as expendable and just wanted to send us to the front so that the Russians could live safely,” he said.

Darbandi said foreign nationals—including Iranians, Africans, Arabs, Kenyans, and Colombians—were segregated from Russian soldiers.

“Foreigners have no rights at all; at any moment, they can take whatever they have,” he said.

He said he was later wounded during a Ukrainian drone strike and captured after being left without assistance for days.

Reflecting on his situation, Darbandi said he feels guilt over his forced participation and urged others not to cooperate with governments he accused of exploitation.

“Never help countries like Russia, Iran, and countries that support terrorists. Please stop the war.”

The account has not been independently verified. Iranian, Russian, and Ukrainian officials have not publicly commented on the case.

Recruitment drive in Tehran

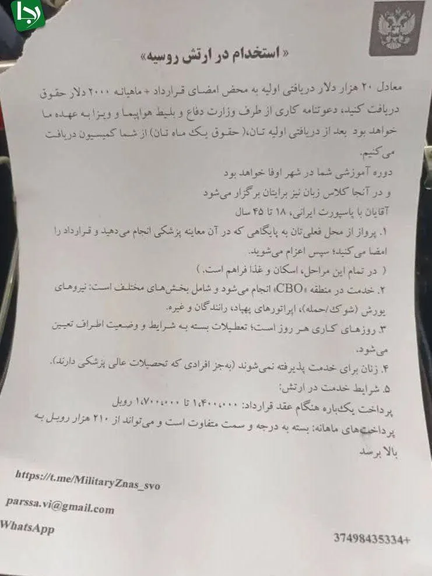

Earlier this month, flyers circulated near the Russian Embassy in Tehran that invited men to enlist in the Russian army for promises of dollar payments and contracts “directly under the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation.”

The Russian embassy denied any connection to the leaflets.

The flyers targeted men aged 18 to 45 and offered starting bonuses of $15,000 to $18,000 and monthly salaries of $2,500 to $2,800, along with free housing, medical care, and military uniforms.

Tehran-based outlet Rouydad24 said the leaflets directed readers to a Telegram channel that had published multilingual posts in Persian, Russian, Arabic, and English, describing the campaign as a “state-supported initiative.”

The Iranian report compared the flyers to similar alleged recruitment efforts in India, Nepal, Sri Lanka and several African countries, which foreign media have described as part of Moscow’s drive to attract foreign fighters amid heavy losses in Ukraine.