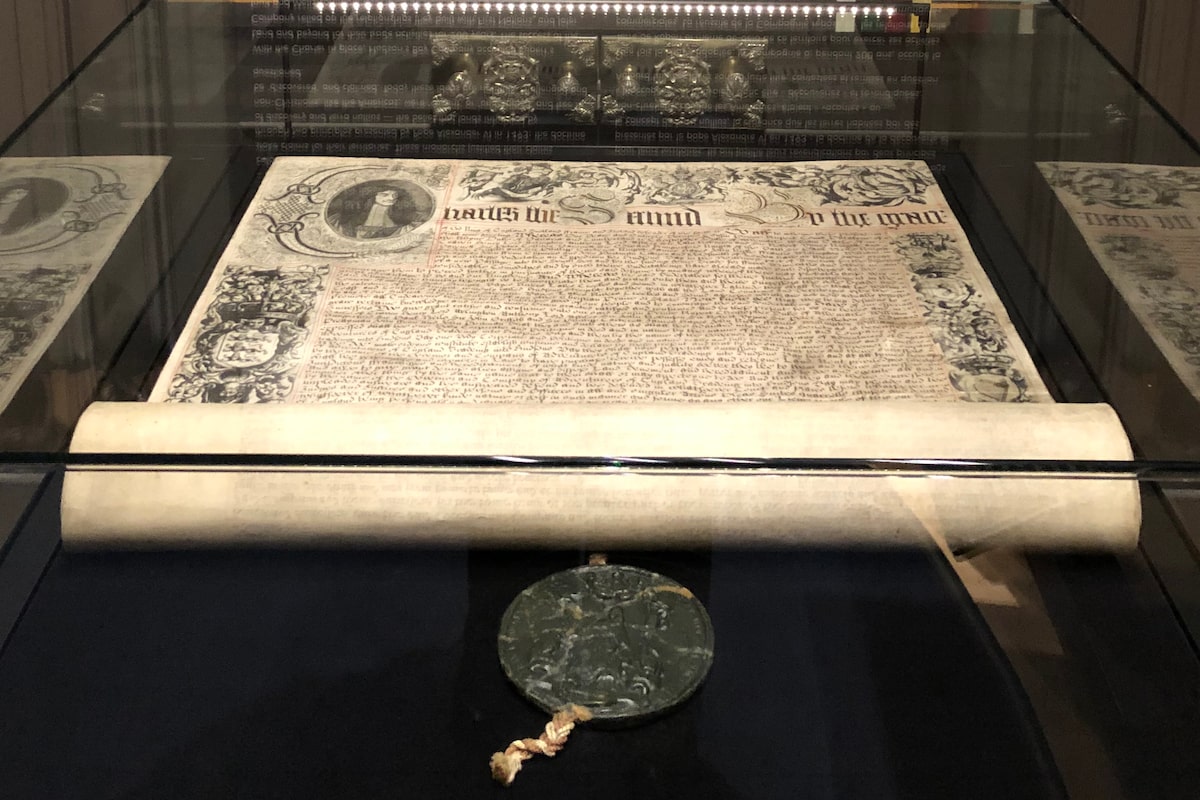

The billionaire Weston family presented a $12.5-million offer for the 1670 royal charter that launched the Hudson’s Bay Co., with plans to donate it to the Canadian Museum of History.HO/The Canadian Press

In presenting their $12.5-million offer for the 1670 royal charter that launched the Hudson’s Bay Co. – a one-of-a-kind document that played a major role in Canada’s history – the billionaire Weston family urged those overseeing the sale not to allow the artifact to go up for bidding at auction.

The deal, announced on Wednesday, would see the Westons’ holding company, Wittington Investments Ltd., buy the charter “for immediate and permanent donation” to the Canadian Museum of History, pending court approval.

That would ensure an “important article of the Canadian origin story” remains in the country and accessible to the public, Wittington’s managing director of strategy, Ryan Markle, wrote in a June 18 letter to the financial adviser and the court monitor overseeing the process.

This was also a concern raised by historians when news of the document’s possible sale emerged in the spring, as the retailer prepared to sell off assets to pay back its lenders. Struggling with mounting losses and $1.1-billion in debt, Hudson’s Bay filed for court protection from its creditors in March.

Mr. Markle also suggested that Wittington might not be willing to participate in an auction process, which had initially been contemplated as part of the Hudson’s Bay insolvency.

“Given its historical significance, Wittington is of the view that the Charter belongs in the Museum and should not be the subject of a standard auction or commercial realization process, and it is not its intention to trigger one with this offer,” he wrote, adding that Wittington’s offer represented certainty for Hudson’s Bay’s creditors, who are owed millions. “There can be no assurance that this offer will remain available if Wittington is not comfortable with the process to be followed in respect of the Charter.”

At a hearing in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice in Toronto on Thursday, lawyers for Hudson’s Bay asked the judge to establish a deadline of Aug. 21 for any party who wants to declare their intention to oppose the approval of the Wittington deal. A hearing into the motion to approve the deal is set for Sept. 9.

“The Charter obviously is a very significant document and has historical significance for all Canadians,” Justice Peter Osborne said at the hearing. He added that he did not want the motion to be brought before the court on short notice, to give adequate time for all parties who are interested in the fate of the document to consider the materials. That includes Indigenous groups, cultural institutions and government representatives.

The Globe and Mail first reported on plans for the auction in April, revealing that the charter was listed in a confidential memo sent to potential bidders for the Hudson’s Bay assets. Part of that memo, which was obtained by The Globe, advertised the retailer’s collection of art and artifacts, and compared the value of the document to the U.S. Declaration of Independence and the Canadian Constitution.

Robert Heffel, vice-president of Heffel, the company running the auction, declined to comment on the loss of the charter, the sale’s lead item.

Mr. Markle wrote that Wittington’s offer price exceeded the most recent appraisal value for the charter. “It is highly uncertain that any other buyer would pay the same or more than Wittington is offering on the same timeframe, let alone commit to donating it to a Canadian public cultural institution with a concurrent significant financial donation,” he added, referring to $1-million the Westons have pledged to give to the museum. Those funds would facilitate a consultation process with Indigenous groups on how the charter would be shared and presented.

The charter is written on parchment and includes the wax seal of King Charles II. It was previously displayed at the Hudson’s Bay corporate offices in Toronto.

The document granted exclusive trading rights to the Hudson’s Bay Company, covering a swath of land within the drainage basin of Hudson Bay. Relying on the doctrine of terra nullius, the charter claimed the land without the consent of the Indigenous peoples who already resided there.

It is difficult to assess how much a one-of-a-kind historic document like the charter would be expected to achieve at auction, said Rob Cowley, president of art auction house Cowley Abbott. He called the Westons’ offer price “very generous,” and added that in Canada it is quite rare to see a piece acquired for greater than $10-million.

“It certainly places it in the stratosphere. I think it’s deserving,” said Mr. Cowley, who was not involved in consultations on the deal.

Values ascribed to other significant historical documents have varied widely.

A manuscript copy of the 13th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, abolishing slavery in that country and signed by Abraham Lincoln, was sold at auction for US$13.7-million in June. An “Authorized Edition” of the Emancipation Proclamation, also signed by president Lincoln, sold at the same auction for US$4.4-million.

An original printed copy of the U.S. Declaration of Independence sold for US$2.4-million last January. One of less than 100 in existence, most of which are held by institutions and never come up for sale, the document was estimated to fetch between US$2-million and US$4-million, and sold at the bottom end of the estimate (with a buyer’s premium then raising the final price tag to US$2.4-million).

A 1660 document that restored Charles II to the monarchy, arguably as important to British history as the charter is to Canadians, was estimated at £400,000 to £600,000 ($750,000 to $1.2-million) in a Sotheby’s 2023 auction of royal papers and memorabilia – but failed to sell.

There are only two surviving copies of the Declaration of Breda, the signed letter in which Charles set out his terms for returning to the throne after the English Revolution, and the other is in Britain’s Parliamentary Archives.

“I think this seems like a fairly good outcome,” said Cody Groat, an assistant professor of history and Indigenous studies at Western University, whose research focuses on the preservation of Indigenous cultural history. Prof. Groat added that as a Crown corporation, the Canadian Museum of History’s interpretation of its exhibits have in the past “been influenced in certain ways by the perspective of the government of the time.”

He said it was unique to see the provision in the deal for the additional funding for the consultation process.

“I hope they don’t frame it as being of solely past-tense significance,” said Prof. Groat, who is Mohawk and a band member of Six Nations of the Grand River. He noted that Indigenous nations still cite the charter in contemporary land claims cases. “This document still has current implications.”