Astronomers have unveiled the most detailed low-frequency radio image of the Milky Way ever produced, an enormous patchwork of cosmic light and color revealing thousands of structures across the galaxy’s southern sky. Captured from the red-dirt heart of Western Australia, this image offers a sweeping and intricate view of the Milky Way like we’ve never seen before.

The work was carried out by researchers at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR), who spent years collecting and processing data from the Murchison Widefield Array telescope (MWA). The final image is sharper, broader, and far more sensitive than any previous view of the Milky Way’s southern hemisphere. It took over one million CPU hours to process.

Unveiling Details across the Galactic Plane

At the heart of this new image is a simple goal: see more, and see it more clearly. Previous attempts to image the Southern Galactic Plane at low radio frequencies were useful but limited. According to ICRAR, this updated release from the GLEAM-X survey delivers twice the resolution and ten times the sensitivity of earlier efforts, plus it covers twice as much of the sky.

The telescope used, the MWA, is located on Wajarri Yamaji Country in Western Australia, a region known for its radio quietness (and its remoteness). Using this site, astronomers collected data across 141 nights between 2013 and 2020.

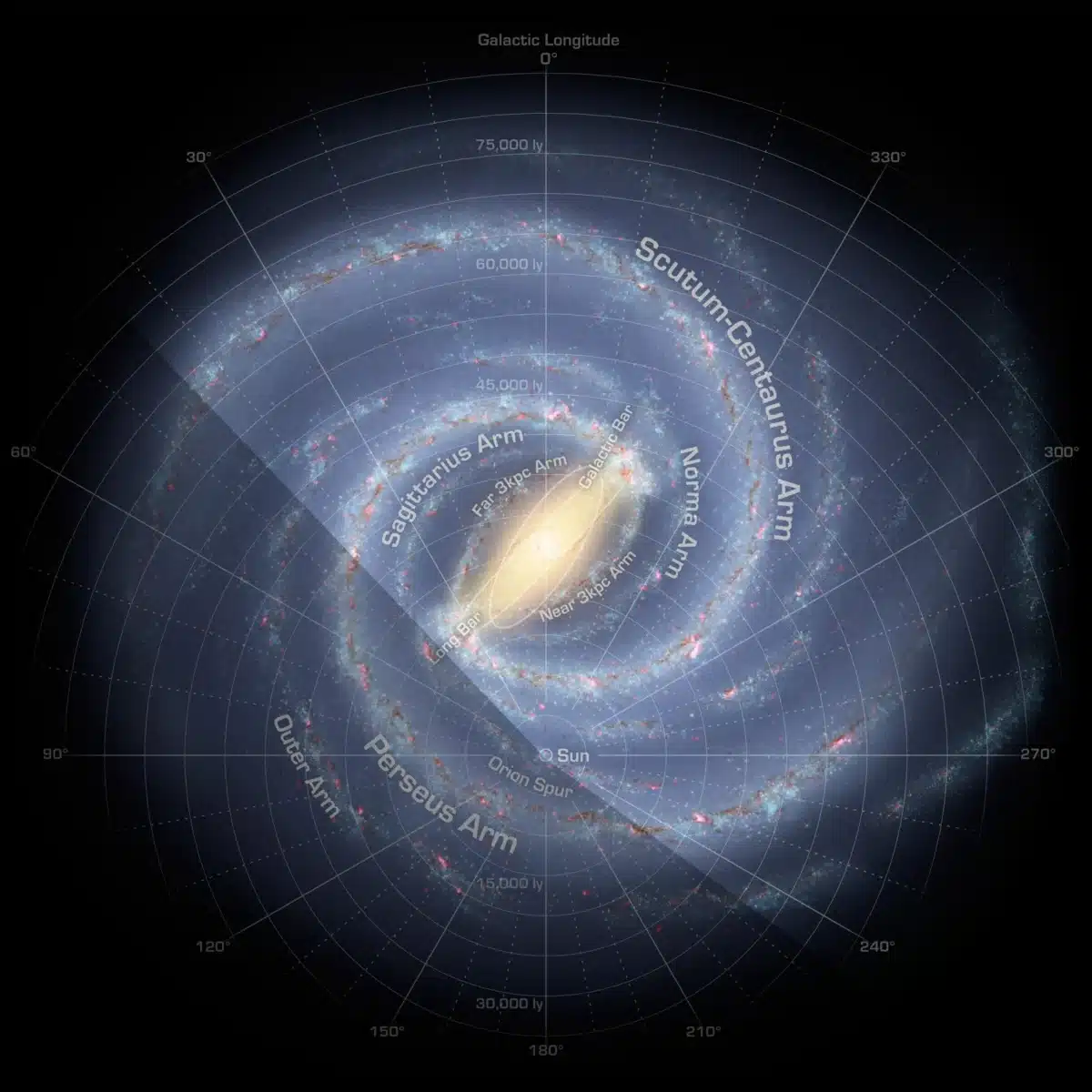

Artist’s concept of the Milky Way seen from above. Credit: NASA

Artist’s concept of the Milky Way seen from above. Credit: NASA

Different slices of the sky were observed in various low-frequency bands, then colored and blended into one detailed image. These frequencies don’t show up in visible light, but they offer a unique view into the behavior of cosmic gas and dust. Silvia Mantovanini, a PhD student at Curtin University, led the complex task of assembling the final image.

“You can clearly identify remnants of exploded stars, represented by large red circles. The smaller blue regions indicate stellar nurseries where new stars are actively forming,” she told SciTechDaily.

Charting a Star’s Life From Birth to Afterlife

A major strength of the new survey lies in what it reveals about stellar evolution, not just how stars are born, but how they die. Mantovanini’s focus has been on supernova remnants, which are notoriously difficult to find in the cluttered background of the Milky Way. Hundreds are already cataloged, but astronomers believe thousands more are still hidden in plain sight.

Top: GLEAM-X radio view. Credit: S. Mantovanini & team. Bottom: Visible light view. Credit: Silvia Mantovanini & the GLEAM-X Team

Top: GLEAM-X radio view. Credit: S. Mantovanini & team. Bottom: Visible light view. Credit: Silvia Mantovanini & the GLEAM-X Team

With this new level of resolution, those leftovers from stellar explosions are easier to spot. You can think of them as vast cosmic scars, expanding clouds of gas and magnetic fields, shaped by ancient cataclysms. This survey helps separate them from the noise and offers a better chance at identifying the missing ones.

The image also offers insight into pulsars, the spinning, radio-emitting remnants of collapsed stars. As reported by the ICRAR team, measuring pulsar brightness across different radio bands could improve our understanding of how they function and where they live in the galaxy.

Setting the Stage for the Next Generation

This release is more than a flashy space photo, it’s a milestone in low-frequency radio astronomy. For the first time, the entire southern section of the Milky Way’s Galactic Plane has been mapped at these wavelengths. As stated by Associate Professor Natasha Hurley-Walker, who leads the GLEAM-X survey:

“No low-frequency radio image of the entire Southern Galactic Plane has been published before, making this an exciting milestone in astronomy.”

The MWA telescope, though powerful, will eventually be surpassed by the upcoming SKA-Low array, currently under construction in the same region. Once operational, the SKA Observatory will be able to deliver even sharper, deeper views of the universe, though let’s be honest, that’s a few years off.

For now, what the GLEAM-X team has built is a foundation. The image catalogs over 98,000 radio sources, from dense HII regions and pulsars to distant galaxies that have nothing to do with the Milky Way. It’s a dense, glowing map of our neighborhood in the cosmos, one that future generations of astronomers will use, refine, and expand upon.