A recently proposed class of magnets, so-called altermagnets, combine features of ferromagnets and antiferromagnets. We discuss the scientific appeal of altermagnets, current controversies and challenges for their practical use.

Magnetic materials come in many forms. Ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic compounds have received the most attention for both fundamental research and practical applications. The spins of ferromagnets align in the same direction, creating a strong magnetic field, whereas antiferromagnets have opposite spins that cancel each other out, resulting in no net magnetization. Recently, researchers have discovered a new magnetic phase called altermagnetism.

Credit: Adapted from Song, C. et al Nat. Rev. Mater. 10, 473–485 (2025), Springer Nature Ltd

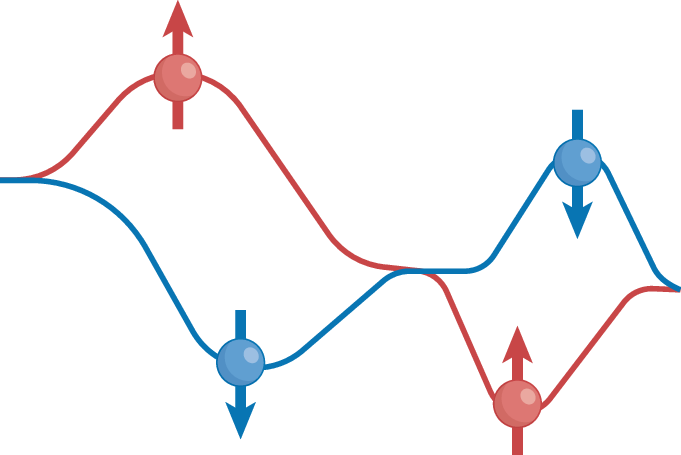

First proposed in 20221, altermagnets bring together defining aspects of ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic order. Like ferromagnets, they exhibit spin-dependent splitting of electronic bands (pictured) — meaning spin-up and spin-down electrons occupy slightly different energy levels — while maintaining zero net magnetization, a hallmark of antiferromagnetism. These features are caused by a symmetry-driven spin arrangement with opposite-spin sublattices that are connected by mirror or rotational symmetry1. This configuration also breaks time-reversal symmetry.

Following the theoretical proposal, angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy studies on MnTe revealed considerable band splitting, a key signature of altermagnetism2,3. However, band splitting alone may not be sufficient to classify a material as an altermagnet. In a recent Comment in Nature Physics, Qihang Liu and colleagues argued that to firmly establish altermagnetic order, the symmetry operations connecting sublattices with opposite magnetic moments must be neither inversion nor translation4. This underscores the importance of combining spectroscopic evidence with rigorous symmetry analysis when classifying new altermagnetic compounds.

Not all materials initially proposed as altermagnets have withstood detailed scrutiny. For example, recent investigations of RuO2 — once considered a promising candidate5 — found no evidence of magnetic order6. However, studies exploring the magnetic ground state in this compound revealed that internal strain may play a critical role in determining whether the particular RuO2 sample orders magnetically or not7.

These findings have sparked an ongoing debate on the characterization of altermagnets, highlighting the importance of sample purity and well-defined experimental and theoretical criteria for altermagnetic behaviour.

In ferromagnets, the order parameter, which describes the degree of magnetic order, equals the net magnetization. However, in altermagnets, the situation is more complex because of the underlying symmetry restrictions. This has led to active discussions within the research community trying to resolve what the order parameter of an altermagnet is.

Recent studies have proposed that magnetic multipoles may serve as the defining order parameter for altermagnetic behaviour8. This idea has motivated experimentalists to develop methods for measuring these multipoles7 and theorists to build a comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

From the standpoint of applications, ferromagnets and antiferromagnets each have their strengths and limitations. Ferromagnets enable spin-polarized currents and their net magnetization makes them valuable for data storage and magnetic sensors. However, they also produce noise through stray magnetic fields and their commercialization faces scalability issues. In contrast, antiferromagnets offer robustness against small magnetic field perturbations and ultrafast spin dynamics for faster operation, but they lack spin-polarized currents, limiting their use in spintronics, which uses spin-based mechanisms instead of charge alone.

Altermagnets have the potential to overcome these issues by combining features of both. The spin-split band structure of altermagnets produces anomalous electronic transport responses, such as the anomalous Hall effect and magneto-optical Kerr effect, without needing spin–orbit coupling. This is helpful for spintronic device applications. Their fast spin dynamics and symmetry-driven transport make altermagnets ideal for memory devices, logic gates and sensors. Researchers are exploring their use in terahertz nano-oscillators, which are useful for ultrafast wireless communication, and spin-torque devices, which are important for energy-efficient memory and logic circuits. Furthermore, their unique band structures may also lead to topological phases and exotic quasiparticles9. Apart from potential technological applications, their symmetry properties may open new research directions in fundamental condensed-matter research.

The prospects for altermagnets are still being assessed amid ongoing debate and experimental challenges. Much of the current work remains theoretical or limited to a few experimental systems. Key challenges include synthesizing suitable materials, understanding their behaviour under ambient conditions and integrating them into device architectures.

Another key requirement for future applications is the availability of metallic compounds exhibiting altermagnetic properties at room temperature. A recent study has successfully demonstrated the existence of such materials10.

Although altermagnets are scientifically intriguing, whether they will indeed open a new chapter in magnetism will depend on experimental and theoretical progress and a clear demonstration of their advantages over existing magnetic materials in practical applications.