Chemistry textbooks explain how reactions start and end, but they rarely show what happens in between. Seeing these hidden moments matters because chemistry is ultimately governed by quantum rules.

By capturing how electrons and nuclei move together in real time, scientists can finally test whether quantum theory truly describes chemical reactions, and uncover effects that may only appear when bonds form and break.

However, until now, observing these processes directly seemed impossible, as electrons shift and atoms rearrange themselves at ultra-fast speeds. Now, a team of researchers from Shanghai Jiao Tong University has taken a major step toward changing that.

Using an advanced form of ultrafast electron diffraction, the researchers have managed to image both electrons and atomic nuclei moving in real space as a molecule breaks apart.

“The investigation of electron dynamics holds substantial significance for advancing fundamental physics and for applied research in materials and chemical sciences,” Dao Xiang, senior study author, told Phys.org.

Tracking electrons and atoms in motion

Traditional diffraction techniques are excellent at tracking heavier atomic nuclei, but they struggle to detect subtle changes in electron density. As a result, scientists could see atoms move but not the electrons that drive those movements.

The study authors overcame this problem by pushing ultrafast electron diffraction (UED) to an unprecedented level of spatial and temporal precision. In their experiment, they focused on ammonia (NH₃), a simple molecule that still contains rich electron dynamics.

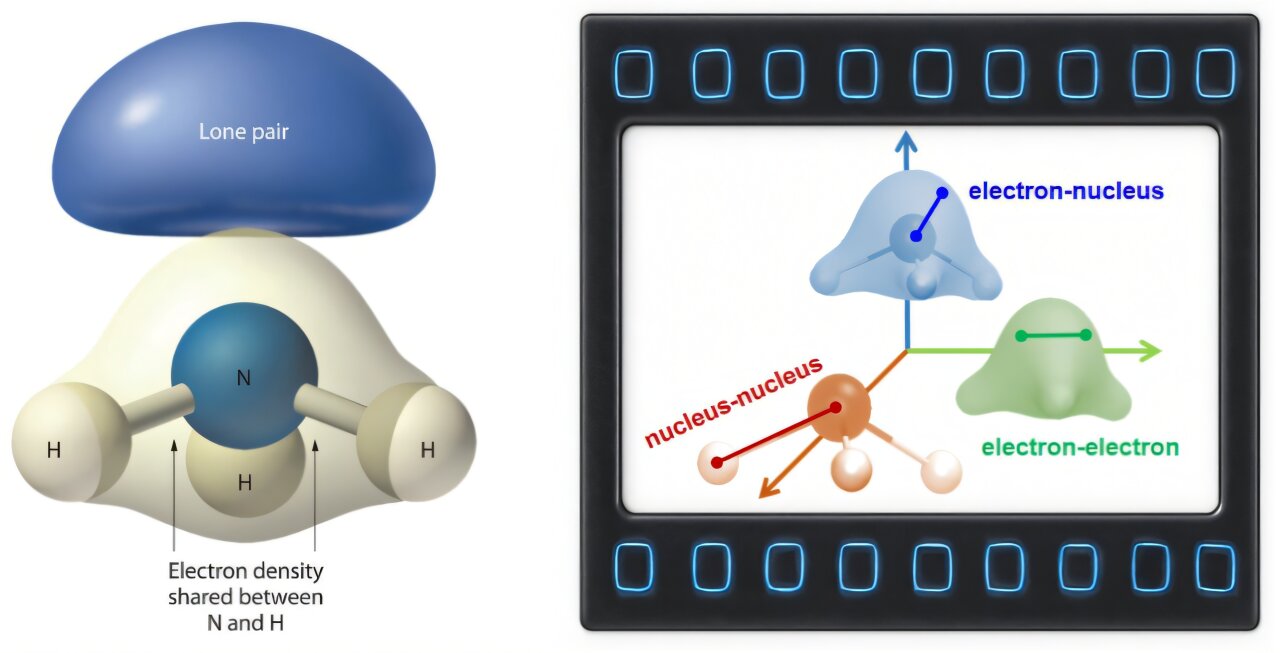

First, the researchers used a short laser pulse about 200 nanometers in wavelength to excite ammonia molecules. This pump pulse promoted an electron from a lone pair orbital on the nitrogen atom into an anti-bonding orbital associated with the nitrogen–hydrogen bond.

This electronic jump triggers a structural change. The molecule bends outward (an umbrella-like motion), and one hydrogen atom begins to separate from nitrogen. “Triggered by the pump pulse, an electron in the lone pair orbital of the N atom is excited to the N-H anti-bonding sigma orbital, leading to the NH3 umbrella motion and N-H dissociation,” Xiang explained.

To track what happened next, the team fired an ultrafast pulse of high-energy (MeV) electrons at the excited molecules. As these probe electrons passed by, they scattered off the electric fields created by both the atomic nuclei and the surrounding electrons.

The resulting diffraction pattern, recorded by a detector, contained hidden information about where charges were located inside the molecule at each moment in time.

Decoding the detected signals

CPDF analysis of the ammonia molecule. Source: H. Jiang at Shanghai Jiao Tong University

CPDF analysis of the ammonia molecule. Source: H. Jiang at Shanghai Jiao Tong University

An important highlight of the study is how the researchers analyzed this signal. They applied a method called charge pair distribution function (CPDF) analysis. “We performed the charge pair distribution function (CPDF) analysis to the experimental diffraction intensity, which allows concurrent imaging of both valence electrons and hydrogen dynamics,” Xiang said.

CPDF allowed them to separate and visualize three types of interactions at once: nucleus–nucleus, electron–nucleus, and electron–electron correlations. This made it possible to map how valence electrons shifted and how hydrogen atoms moved simultaneously.

Thanks to the high sensitivity and signal quality of their setup, the team could even track hydrogen motion. something notoriously difficult because hydrogen scatters electrons very weakly and moves extremely fast.

The result was a real-time, real-space picture of how electronic orbitals change, how electron density evolves, and how atoms respond during the photodissociation of ammonia—something previous methods simply could not achieve.

Harnessing the potential of UED

This work marks an important advance for both chemistry and physics. By showing that UED can directly detect valence electron rearrangements, the study moves beyond models that treat atoms as independent, static scatterers.

Instead, it reveals the electronic activity that actually governs chemical reactions. In the long run, this capability could improve our understanding of reaction mechanisms, energy transfer, and quantum effects in molecules.

“Our analysis successfully revealed the abundant electronic dynamics encoded in the UED signal, including electronic orbital transition, electronic density evolution dynamics, and electron-electron correlation,” Xiang added.

However, the technique also has limitations. For instance, the signals from electrons are subtle and can easily be overwhelmed by scattering from heavier atoms.

Next, the researchers will find ways to refine their approach and apply it to other systems. “We will now extend our methodology to other molecular systems, demonstrating the capability of electron diffraction to detect signatures of valence electron rearrangement even in complex organic molecules,” Xiang concluded.

The study is published in the journal Physical Review Letters.