Researchers at Polytechnique Montréal have succeeded in mapping blood flow in the brain with unprecedented precision, which could one day make it possible to detect early signs of neurodegenerative diseases.

Professor Jean Provost’s team notably achieved the feat of imaging blood capillaries, those tiny channels where gas exchange occurs between the blood and cells.

“We apply the localization principle which is the 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry (…) to be able to see much finer structures than what can be seen in a normal ultrasound image,” summarized the Montreal researcher.

Health problems such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, and strokes cause subtle changes within the brain, even in the absence of apparent symptoms. For example, blood flow in the capillaries is altered, which can harm neighboring cells by depriving them of essential nutrients.

However, these changes occur on such a microscopic scale that they escape current medical imaging techniques.

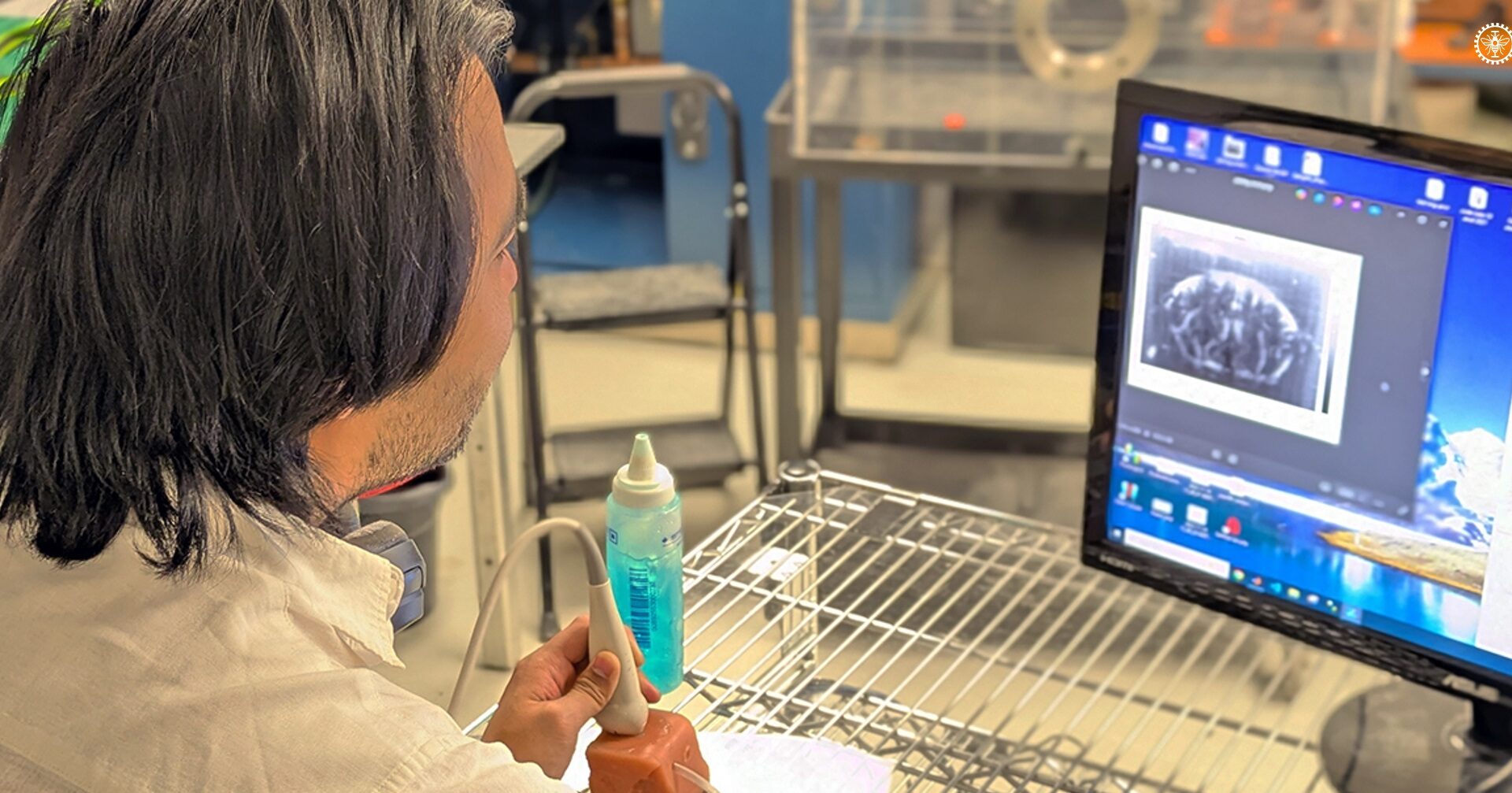

Ultrasound localization microscopy (ULM), conceived by Professor Provost and his colleagues, follows the path, in the bloodstream, of tiny bubbles that could be compared to soap bubbles.

These microbubbles are already commonly used for imaging purposes in cardiology, but the technique faces certain limitations since the capillaries are so small that they only allow one red blood cell (or in this case, one microbubble) to pass through at a time.

Postdoctoral researcher Stephen Lee therefore proposed to follow the path of a single microbubble among the hundreds that were injected, an approach that was dubbed SCaRE (for Single Capillary Reporters).

“Thanks to the speed at which the bubble moves and its movement, we are able to statistically determine whether it is a capillary,” he explained. “So we are still observing individual bubbles, but we have a statistical method capable of determining whether one of them exhibits the appropriate behavior or not.”

Rather than considering each microbubble as a simple point used to reconstruct a complete representation of a capillary, it was explained in a press release, “the researchers analyze its movement from image to image to obtain its trajectory and measure the change in its speed of movement.”

In addition to imaging the capillary, the SCaRE approach makes it possible to assess its health by estimating the time it takes a microbubble to pass through it, an approach that the team was able to demonstrate on a model of neuroinflammation in mice.

If blood flow stops in a capillary – a problem known as “stalling” in English and normally only seen by removing part of the skull – complications can probably be anticipated, Professor Provost said.

“We are able to see this ‘stalling’ phenomenon not just on the surface of the brain, but throughout the entire brain,” he emphasized, and this without surgery.

Scientists, Professor Provost added, “are quite confident that capillaries play a role in neurodegenerative diseases.” Therefore, the use of this technology could be considered for early detection or screening, he said.

Its deployment in hospitals is not imminent. Acquisition times remain long, and 3D imaging is currently unattainable. However, the use of ultralight aircraft (ULM) to detect early signs of neurodegenerative diseases can be realistically envisioned.

“We want to create digital maps of the entire vascular system so that we can analyze the brain as a whole in a completely different way than we have been able to do so far,” concluded Lee.

“There is a strong demand for personalized medicine applications. I think it’s a great way to create personalized digital models of the brains of different individuals, so that we can examine them, study them, and determine if one patient needs very specific treatment compared to another patient, even if they suffer from the same disease. That’s something that excites me a lot.”

Details of this breakthrough are published in the scientific journal PNAS.

–This report by La Presse Canadienne was translated by CityNews