Published on Jan. 19, 2026, 7:19 PM

Updated on Jan. 19, 2026, 7:40 PM

Sparked by a fast-moving solar storm, the Northern Lights may stretch far to the south tonight, and might even be visible from the southern United States.

Eyes to the sky tonight, for a chance to spot another amazing display of the Northern Lights! It all comes down to the exact timing of when a speedy solar storm sweeps past us as it blasts away from the Sun.

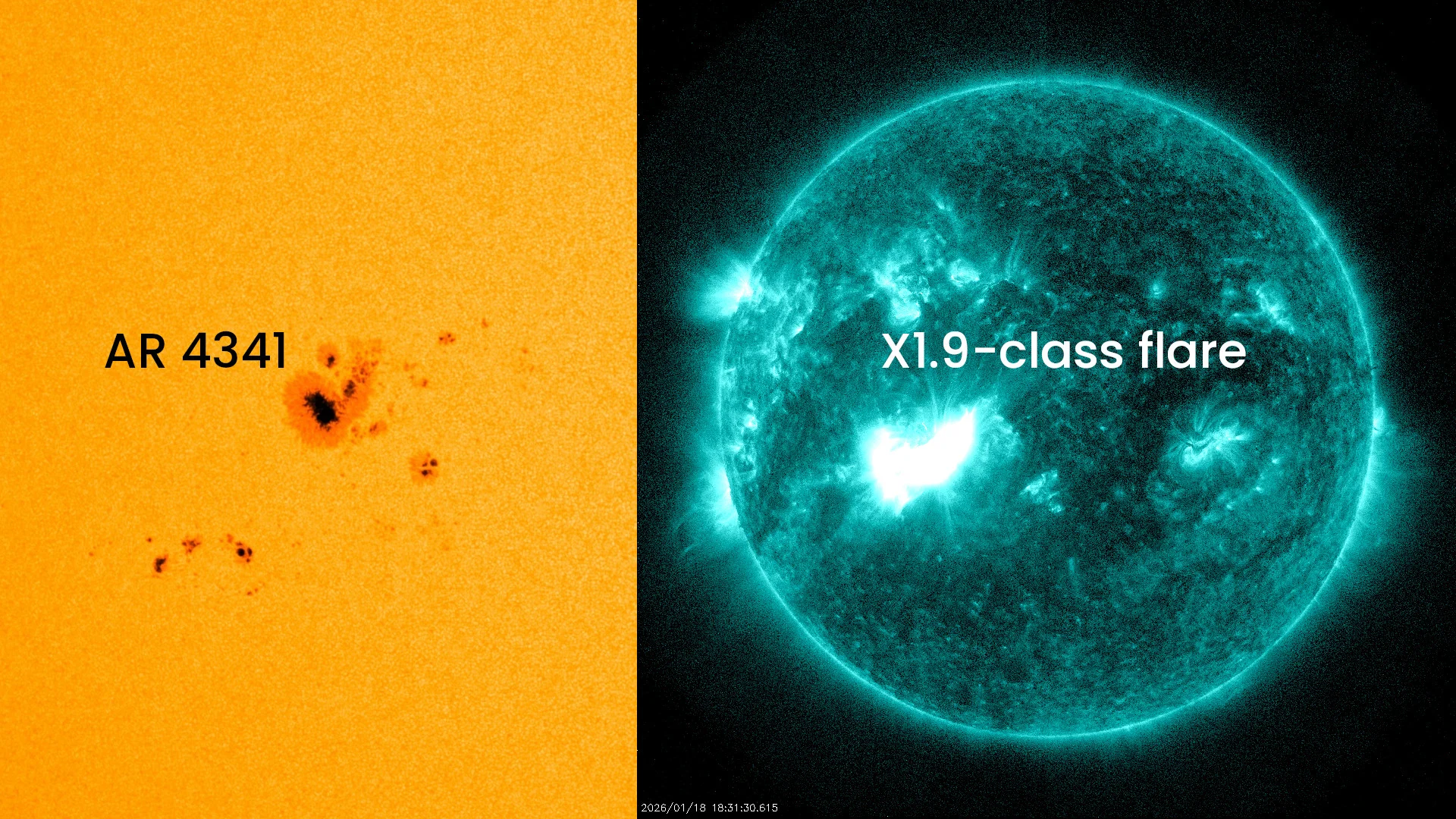

Around midday Sunday, a large sunspot known as AR 4341, which has been crackling with activity since it first appeared last week, exploded in an intense X1.9-class solar flare. From the initial spike of energy to when it finally tapered off, this long-duration flare lasted for roughly 7 hours.

Active Region 4341 (left), with the X1.9-class solar flare captured by satellite imagery on Sunday, January 18, at 18:31 UTC. (NASA SDO)

The powerful shock from this flare, along with the energy and x-rays it poured into space, touched off two follow-up impacts.

The first was a solar radiation storm, as the flare energized solar protons, causing them to rocket away from the Sun at very high speeds. According to NOAA, as of Monday afternoon (EST), this radiation storm has now reached S4 (severe) levels. This could expose astronauts on orbiting spacecraft, as well as crew and passengers on aircraft flying over the Arctic, to radiation risks.

The second impact was a massive cloud of solar matter, known as a coronal mass ejection or solar storm, which erupted into space. This CME absorbed the brunt of the energy from the flare, resulting in a very fast-moving cloud of charged solar particles, which is expected to reach Earth only around 30 hours after it erupted. Typical CMEs take anywhere from three to four days to reach us after they erupt.

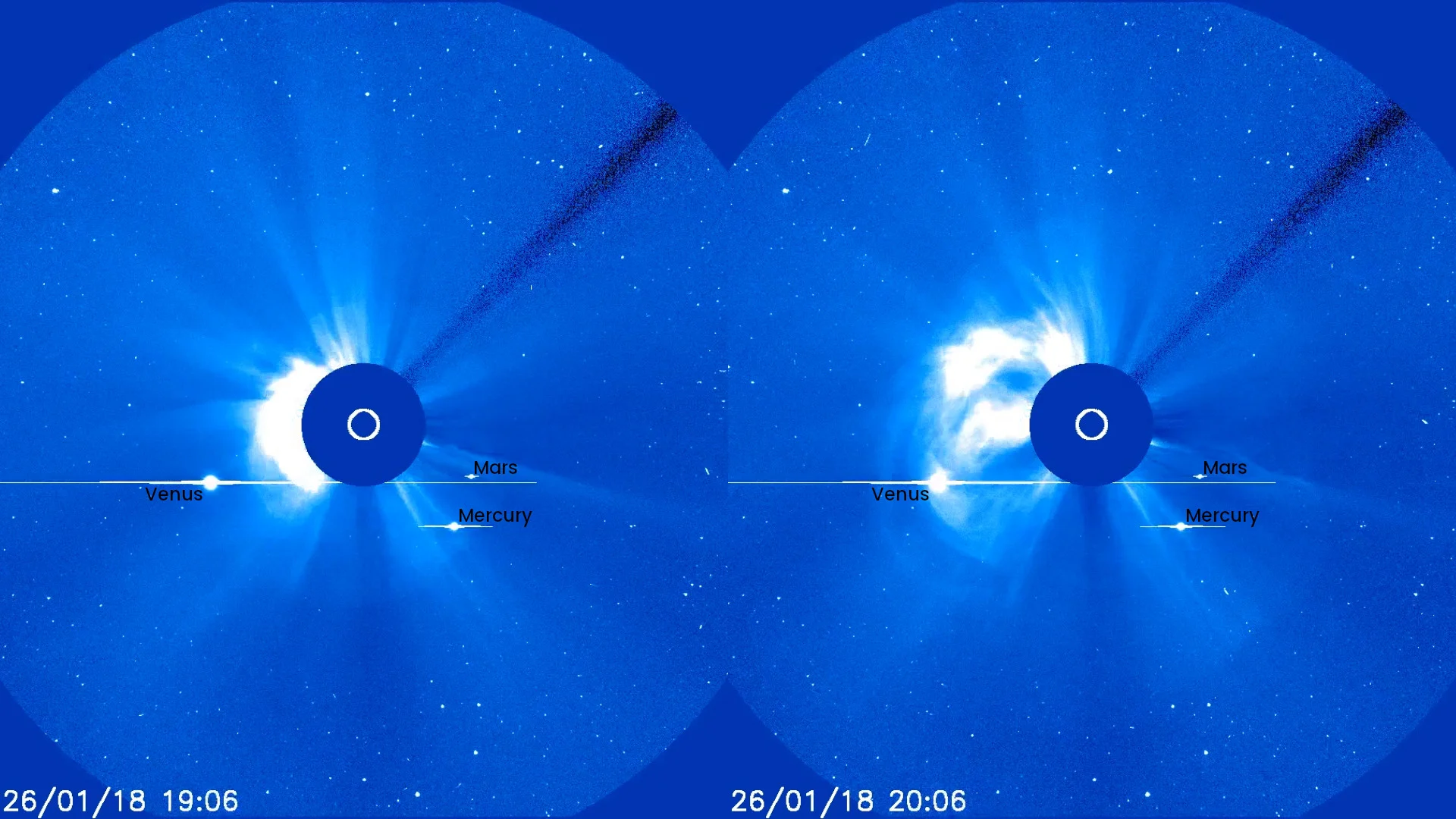

Two coronagraphs of the January 18 2026 CME, taken one hour apart, show the erupting CME expanding mainly towards the left. A fainter ‘halo’ can also be seen, indicating that a portion of the cloud is headed towards Earth. The planets Venus, Mars, and Mercury are labelled. (Scott Sutherland/NASA ESA SOHO)

Coronagraph imagery taken after the eruption, as shown above, reveals that the bulk of the CME was directed towards the space ‘behind’ Earth in its orbit. Thus, the densest portion of the cloud will likely miss us. However, the imagery also shows that this was a ‘halo’ CME, meaning that some portion of the cloud is headed directly for us.