A telescope on the Moon could soon expand our view of the universe’s darkest giants. A recent study shows that placing a radio observatory on the lunar surface, paired with existing Earth-based arrays, could make it possible to directly observe the shadows of dozens of supermassive black holes.

While current technology has managed to capture blurry images of only M87 and Sagittarius A (Sgr A*), the proposed Moon-Earth telescope network could achieve sub-microarcsecond resolution, revealing detailed structures of other nearby black holes once thought beyond reach.

Earth-Based Radio Arrays Have Hit Their Resolution Ceiling

So far, the only black hole shadows ever directly imaged are those of M87, located in the Virgo galaxy cluster, and Sgr A, at the center of our own Milky Way. Both images were made possible through the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), a coordinated global array of ground-based observatories operating at 230 GHz. As stated in the study published by Zhao et al., the resolution of such arrays is limited by the Earth’s diameter, only about 20 microarcseconds.

Due to the long wavelengths of radio signals, radio telescopes require immense baselines to achieve high resolution. Optical telescopes can rely on shorter wavelengths to achieve sharp images with smaller instruments, but in radio astronomy, resolving something as small as a black hole shadow demands massive distances between observatories. Even with upgrades like the next-generation EHT (ngEHT), expected to improve angular resolution to roughly 10 microarcseconds, the limit remains too high to image anything smaller or farther than M87* and Sgr A*.

According to the same source, to resolve finer structures, such as the photon rings predicted by general relativity, an even longer baseline is required. The distance between the Earth and the Moon, roughly 384,400 km, could unlock angular resolutions as fine as 0.85 microarcseconds.

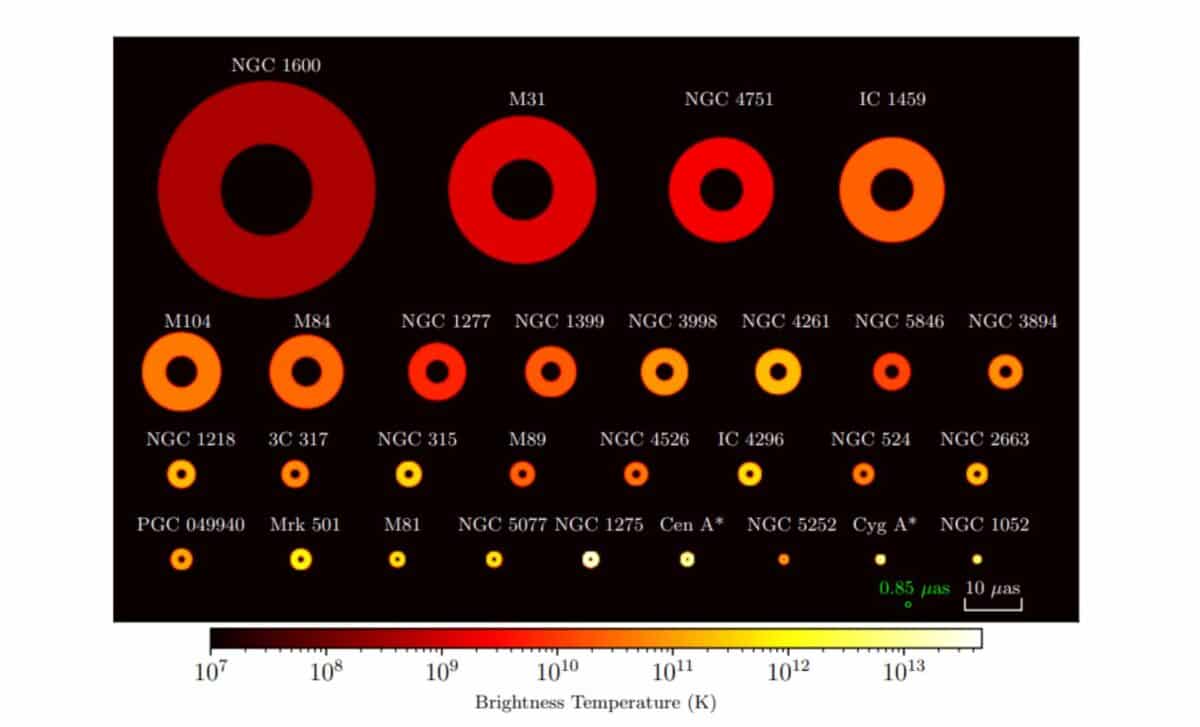

Ring model images of 29 SMBH candidates (Table 1 excludes Sgr A* and M87*), ordered by their ring sizes. ©S. Zhao et al.

Ring model images of 29 SMBH candidates (Table 1 excludes Sgr A* and M87*), ordered by their ring sizes. ©S. Zhao et al.

Six Black Holes Emerge as Strong Candidates for Lunar Imaging

The new study, available in ArXiv, identifies six supermassive black holes with shadow sizes and brightness levels detectable by a Moon-based array, assuming a 100-meter lunar telescope works in tandem with the EHT. These include M104, NGC 524, PGC 049940, NGC 5077, NGC 5252, and NGC 1052. The authors used geometric ring models to simulate visibility data and determine whether the first “null” in the visibility amplitude, a key indicator of a black hole shadow, would be measurable with the proposed configuration.

Among these, M104 (in the Sombrero Galaxy) stands out. Its shadow spans nearly 10 microarcseconds, and its radio flux at 230 GHz is around 198 mJy. According to the paper, even a modest 5-meter antenna on the Moon could detect the visibility nulls needed to confirm the presence of the shadow. NGC 1052, though having a smaller shadow of about 0.9 microarcseconds, is extremely bright, making it another high-priority target for sub-microarcsecond imaging.

Conversely, the detection of NGC 5252 is more challenging. The source is faint, and uncertainties in its mass and distance mean its shadow could fall outside the observable baseline range, even with a 100-meter lunar dish. The authors emphasize that visibility data (not traditional images) would be the key method for detection in such sparse array configurations.

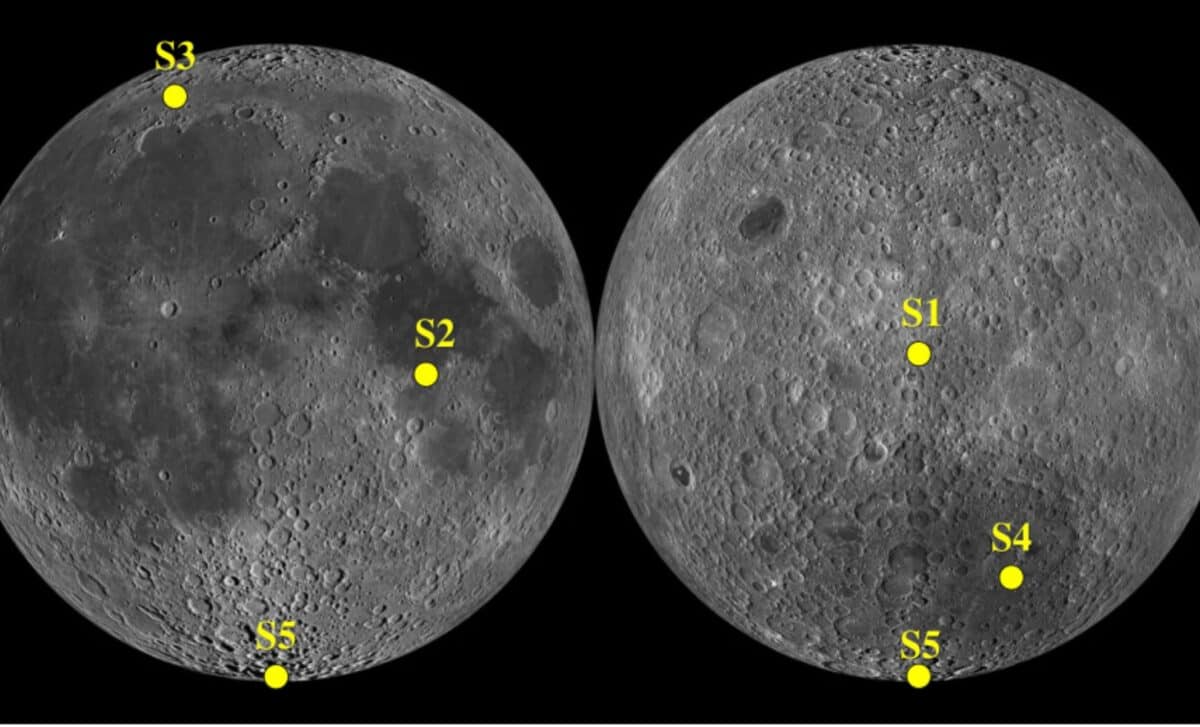

Map of telescope sites on the Moon. ©S. Zhao et al.

Map of telescope sites on the Moon. ©S. Zhao et al.

Site Selection and Technical Limitations Remain a Major Hurdle

The Moon offers several promising locations for radio astronomy. The authors evaluated five candidate sites: two on the near side (including the historic Apollo 11 and Chang’E-5 landing zones), two on the far side, and one at the lunar south pole. The site labeled S1, located at the lunar antipode (the point farthest from Earth) was selected for detailed simulation due to its optimal visibility of all 31 black hole candidates listed.

Observing from the lunar far side has a critical advantage: it’s shielded from Earth’s constant stream of radio interference. This would allow cleaner, uninterrupted data collection, provided the elevation angle of targets is above 15 degrees. According to the study, placement at equatorial or mid-latitude sites provides up to 11 days of visibility for most sources during a lunar sidereal month, while polar sites like S5 could continuously observe southern sky targets but miss those in the north entirely.

In terms of hardware, antenna size is directly tied to detection limits. At 230 GHz, a 5-meter lunar dish can detect only about half of the proposed black hole targets. A 100-meter dish, while more technically demanding, satisfies the sensitivity requirement for all 31 candidates. The study outlines that for the strongest targets, including M104 and NGC 5077, a baseline formed with ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) would allow detection with even smaller antennas.

While we’re still decades from building radio observatories on the Moon, the scientific payoff is clear. A Moon-Earth baseline would extend our reach into the darkest regions of the cosmos, allowing scientists to study black hole shadows with resolution levels that could put Einstein’s general relativity to its sharpest test yet. According to Zhao et al., this next step in space-based interferometry could unlock visibility data for black holes across our cosmic neighborhood, something impossible from Earth alone.