A young, still-forming star has been caught in the act of creating heat-born crystals and hurling them far into the cold outskirts of its planetary disk. Using fresh observations from the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers have traced this process in unprecedented detail around the star EC 53, offering a direct explanation for a mystery that has challenged planetary science for decades. The findings were reported in a peer-reviewed study published in Nature, linking violent stellar youth to the quiet, icy bodies seen in mature planetary systems.

A Longstanding Cosmic Puzzle Finally Comes Into Focus

For years, scientists have known that comets contain crystalline silicates, minerals that only form at extremely high temperatures. This fact never fit comfortably with the frigid environments where comets spend most of their existence. The new observations of EC 53 finally connect these two extremes. Close to the star, intense heat transforms ordinary dust into crystalline material. Webb’s sensitivity then reveals how this material does not stay put but begins a slow, turbulent journey outward through the disk.

This work draws directly on mid-infrared spectroscopy, allowing astronomers to identify minerals with precision while tracking their location over time. The study, published in Nature, shows that crystal formation and transport are not separate chapters but parts of the same continuous process. The system acts as a natural laboratory where theory meets observation, closing a gap between models of star formation and the real behavior of young stellar disks.

Outflows That Act Like a Stellar Conveyor Belt

At the heart of the discovery lies the unusual behavior of EC 53, a young star that experiences regular bursts of activity roughly every 18 months. During these phases, the star pulls in material from its disk while simultaneously expelling gas and dust through layered outflows. These motions turn the inner disk into a launch zone for newly formed crystals.

Jeong-Eun Lee, a professor at Seoul National University and lead author of the study, described the process in vivid terms:

“EC 53’s layered outflows may lift up these newly formed crystalline silicates and transfer them outward, like they’re on a cosmic highway,” said Lee.

She added that Webb’s capabilities were central to this breakthrough:

“Webb not only showed us exactly which types of silicates are in the dust near the star, but also where they are both before and during a burst.”

These observations confirm that energetic winds can bridge the gap between the hottest and coldest regions of a forming planetary system, carrying solid material across distances once thought unreachable.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope’s 2024 NIRCam image shows protostar EC 53 circled. Researchers using new data from Webb’s MIRI proved that crystalline silicates form in the hottest part of the disk of gas and dust surrounding the star — and may be shot to the system’s edges.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope’s 2024 NIRCam image shows protostar EC 53 circled. Researchers using new data from Webb’s MIRI proved that crystalline silicates form in the hottest part of the disk of gas and dust surrounding the star — and may be shot to the system’s edges.

Image: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Klaus Pontoppidan (NASA-JPL), Joel Green (STScI); Image Processing: Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

Earthlike Minerals Found in an Alien Nursery

One of the most striking aspects of the data is the identification of specific minerals familiar from Earth geology. Webb detected forsterite and enstatite, crystalline silicates that also make up a large fraction of our own planet’s interior. Their presence around EC 53 reinforces the idea that the raw ingredients of rocky worlds are widespread across the galaxy.

Dr. Doug Johnstone of the National Research Council Canada emphasized the significance of this connection:

“Even as a scientist, it is amazing to me that we can find specific silicates in space, including forsterite and enstatite near EC 53. These are common minerals on Earth. The main ingredient of our planet is silicate,” noted Dr. Johnstone.

The implication is clear. The materials that eventually build planets like Earth are already being processed and redistributed at the earliest stages of star formation, long before planets themselves emerge.

Mapping Motion, Not Just Chemistry

Beyond identifying minerals, Webb allowed the research team to visualize how matter moves through the system. Fast, narrow jets shoot out near the star’s poles, while broader, slower winds rise from the inner disk. Together, these flows sculpt the environment and determine where solids end up over time.

Joel Green, an instrument scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, highlighted this achievement:

“It’s incredibly impressive that Webb can not only show us so much, but also where everything is,” said Green.

“Our research team mapped how the crystals move throughout the system. We’ve effectively shown how the star creates and distributes these superfine particles, which are each significantly smaller than a grain of sand.”

This ability to track motion transforms abstract models into observable reality, showing a dynamic system where dust, gas, and crystals are constantly reshaped.

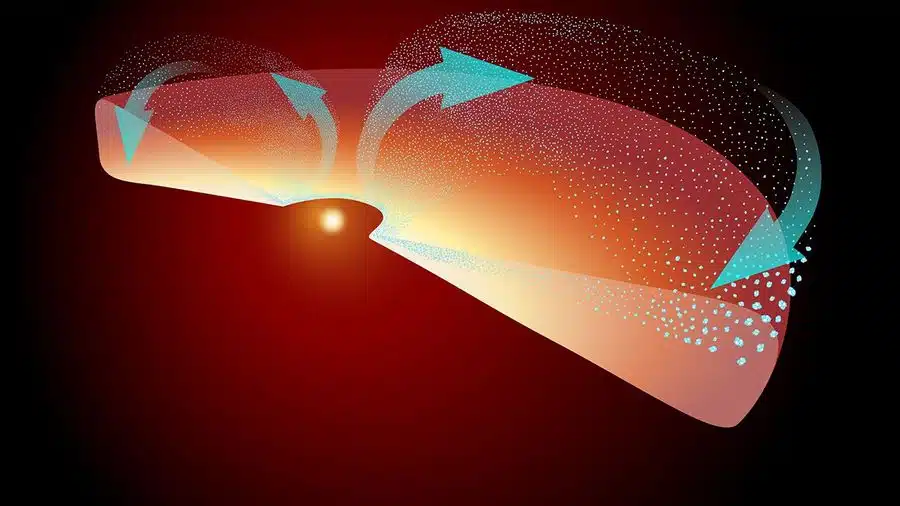

This illustration represents half the disk of gas and dust surrounding the protostar EC 53. Stellar outbursts periodically form crystalline silicates, which are launched up and out to the edges of the system, where comets and other icy rocky bodies may eventually form.

This illustration represents half the disk of gas and dust surrounding the protostar EC 53. Stellar outbursts periodically form crystalline silicates, which are launched up and out to the edges of the system, where comets and other icy rocky bodies may eventually form.

Illustration: NASA, ESA, CSA, Elizabeth Wheatley (STScI)

From Violent Beginnings to Familiar Planetary Systems

EC 53 remains deeply embedded in dust and gas and may stay in this phase for another 100,000 years. Over far longer timescales, collisions between grains will form pebbles, rocks, and eventually planets. The crystals now being flung outward may one day reside in comets or icy bodies at the edge of the system, preserving a record of their fiery origin.

Located about 1,300 light-years away in the Serpens Nebula, this single star offers insight far beyond its immediate neighborhood. By capturing the full journey of crystalline silicates, Webb has revealed how chaos in a star’s youth sets the stage for the calm architecture of mature planetary systems.