Victor “Vic” Maitland sat in the back corner on the second floor of an Italian restaurant in Canton, Ohio, taking suit measurements of several NFL players. A pile of gold jackets lay in front of him.

It was 1978, and he had little time to waste. The next morning was the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s enshrinement ceremony and inductees — Lance Alworth, Weeb Ewbank, Alphonse “Tuffy” Leemans, Larry Wilson and Ray Nitschke among them — needed to fit into their newly minted jackets.

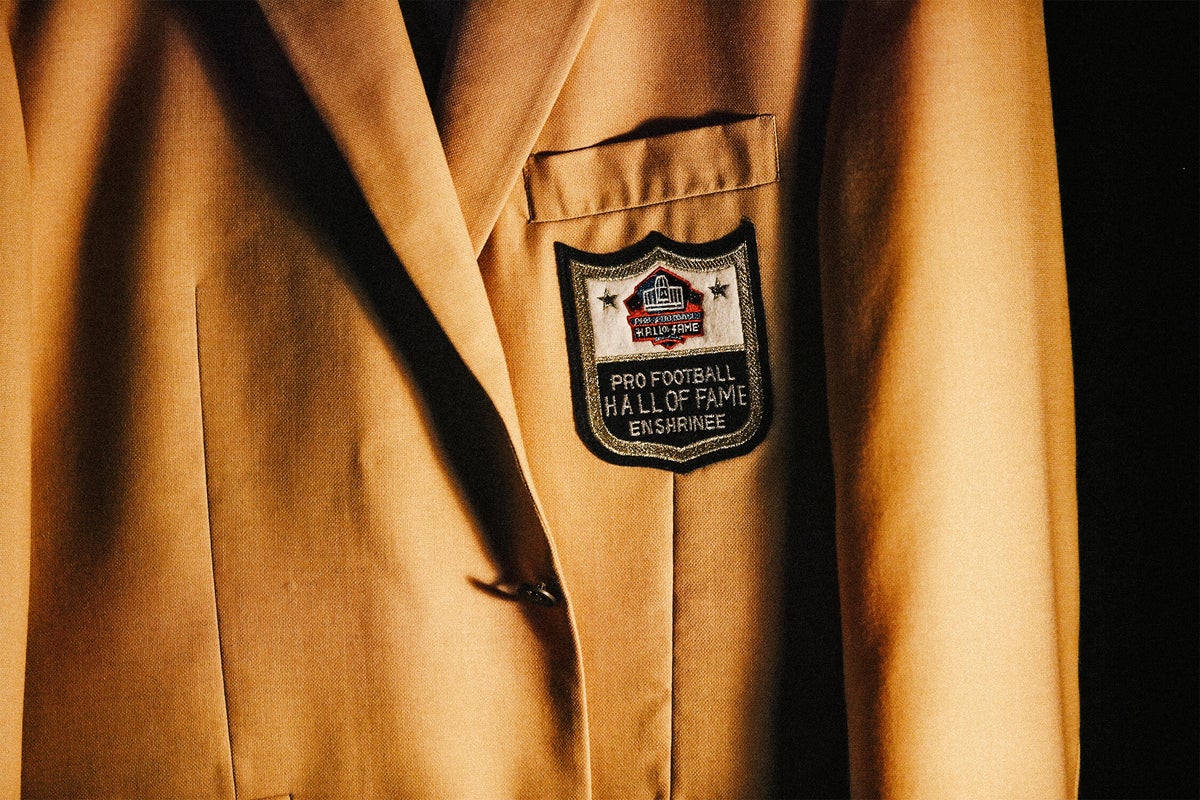

The gold jacket was one of Maitland’s ideas to transform the NFL Alumni Association after becoming the executive director in 1977, at least according to Maitland’s heirs. Each jacket featured a patch with a shield resembling the NFL’s logo, the words “NFL Alumni” and 23 tiny stars. Maitland’s wife, Katherine “Bonnie” Maitland, had sewn on the patches herself.

The jackets were not the symbol of greatness they are today. Like winning a Super Bowl ring, donning a gold jacket has now become synonymous with reaching the “gold standard” of football achievement. “(Inductees) don’t say ‘Becoming a Hall of Famer. They say, ‘Getting a Gold Jacket,’” says Angela Gray, 92, Maitland’s long-time former assistant and one of the few remaining members of that Italian restaurant meeting still alive.

Back in 1978, the jackets were innovative. Bold. Something that football had never seen before. “It was exciting,” Gray says. “Vic was very, very creative. When it came to the gold jackets, Vic said, ‘This needs some oomph to it.’”

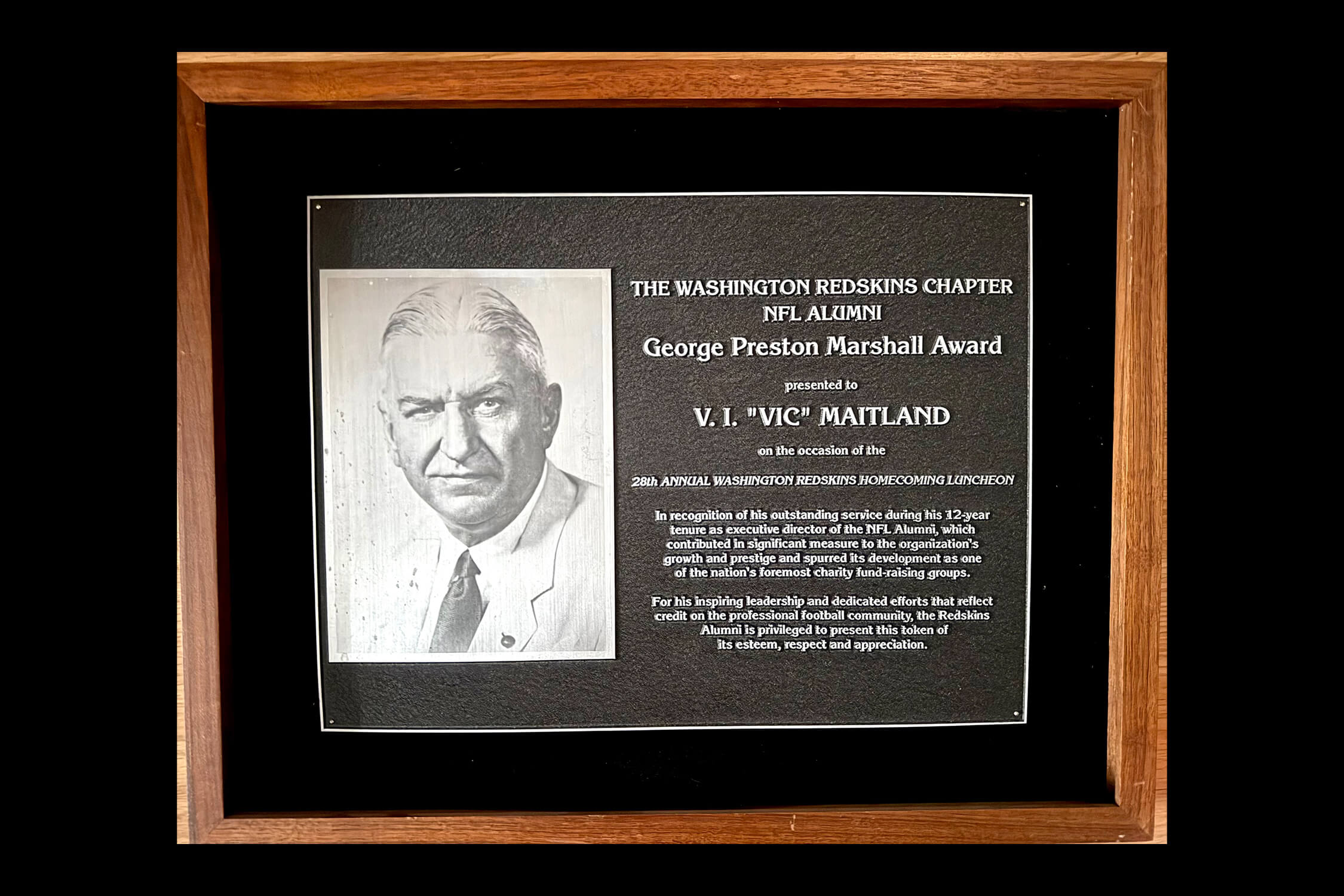

Over his 12-year tenure, which culminated in 1989, Maitland elevated the Alumni Association into a thriving charitable organization that fought for players’ pension rights. He established charity golf tournaments and prioritized fundraising for children in need, calling his efforts “a labor of love” to the Associated Press. He was awarded the Order of the Leather Helmet, the NFL Alumni’s highest honor, in 1986.

“My dad got to know (Vic) pretty well,” says Steelers vice president Art Rooney Jr. “Vic knew the right people, and the right places to be. … He was a guy who helped people who needed it.”

On Jan. 27, 2001, the NFL Alumni Association issued a proclamation awarding Maitland as a “Lifetime Honorary Professional Member” and listing his contributions: “Victor I. Maitland was the driving force behind the institution of the now-established tradition whereby the National Football League alumni presents the famed ‘gold jackets’ to each year’s class of inductees into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.”

But Maitland’s name is nowhere to be found on the Pro Football Hall of Fame website, on its official media guide or in its museum in Canton. His name cannot be found on the NFL’s official website or on that of Haggar Clothing Co., which has remained the manufacturer of the gold jacket since 1978.

Few outside the family have ever heard of Vic Maitland, let alone know about the 2001 proclamation, which was not made public outside of a small ceremony among Alumni members.

“The NFL erased him from history,” says Jim Maitland, one of Vic’s five children.

Maitland transformed the NFL Alumni Association during his 12 years as executive director. (Courtesy of the Maitland family)

But why?

The question lingered among family members for decades, laying dormant until Vic died in 2019 at 98. According to Kathy Lassen, one of his daughters and his primary caretaker over his final five years, he insisted he did not want to say anything about the jacket’s origins “as long as I’m alive.”

“He knew what he did,” Lassen says. “He had great peace with what he did.”

His heirs have not been at peace. Every February, when a new Hall of Fame class is announced during the NFL Honors awards show, each of them remembers their father. They wish others did, too. Over the past two years, they’ve tried to reach out to anyone they could find at the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Alumni Association and the NFL, searching for answers, only to come up empty. They’ve taken it upon themselves to document Vic’s story, especially Lassen, who spent over a year compiling a 74-page biography of her father, interviewing Vic for hours, scanning newspaper articles and other documents, restoring old photos and eliminating scratches to keep his story alive.

When Vic’s granddaughter, Jamie Maitland, began to read that book, she was baffled that so little information existed about the history of the gold jacket. “Nobody knows,” Jamie says. She had personal memories of the energetic family man who seemed larger than life — “He was funny,” she says. “He had a presence.” — but the more she learned, the more she realized she hadn’t really known her grandfather’s legacy at all. She was the catalyst who inspired the family to finally take action. “She’s the one who opened Pandora’s Box,” Jim says.

In August 2025, the Maitlands filed a complaint in US District Court for the Southern District of Florida, alleging that the NFL, NFL Properties LLC, NFL Alumni, National Football Museum Inc. — which operates as the Pro Football Hall of Fame — and Haggar have profited off of Maitland’s creations and that their actions “constitute unregistered trademark infringement.”

“It’s David versus Goliath,” says Mitchel Chusid, the family’s lawyer.

The Pro Football Hall of Fame’s website claims that Haggar is the “creator of the Gold Jacket.” In a 2021, a spokesperson said that the “history of the origin of how (the jacket) came to be is lost.” A spokesperson declined to comment on the Maitlands’ claim while referencing “pending litigation.” A spokesperson for Haggar confirmed the company moved to dismiss the lawsuit but offered no further comment.

In addition to the lawsuit, the Maitlands submitted a formal application to the Pro Football Hall of Fame to honor Vic in its “contributor” category in March 2025.

“America deserves to know the history behind one of the most iconic symbols in football,” Jamie says. “This is a missing piece of history that people just don’t know. Vic left a big imprint on the world. And it got deleted.”

Inside Lassen’s home in Jupiter, Fla., is a framed $1 bill — the one Maitland signed when he took over the Alumni Association in 1977. The organization couldn’t afford to pay him anything, so he took a symbolic salary: a dollar a year.

He didn’t need money; Maitland became a millionaire in the advertising industry after his playing career with the New York Giants and the Pittsburgh Steelers in the mid-1940s, which sandwiched a stint in the army. He founded his own agency, Vic Maitland & Associates, that represented lucrative clients, including Westinghouse, Columbia Gas, AMF and Duquesne Brewing.

Newspapers chronicled his elevation to executive director. “He Works for Nothing to Repay Game He Loves.” (Miami Herald, October 1978); “Maitland Loves his $1 a Year Job” (Associated Press, June 1988).

After retirement from his advertising career, Maitland had no plans to return to the workforce until he and his son Jack were invited by Bill Chip, a friend, to attend a reunion of old-time football players in Canton. After Maitland arrived, he found out it was actually a meeting to figure out how to financially assist players who played before 1959 and were excluded from pensions and benefits available for other NFL players who played afterward. The alumni association, which had been established in 1967, had just a few hundred members and lacked money, leadership and a viable plan for survival.

During this meeting, members realized that Maitland had the marketing chops and leadership skill to pull the organization out of turmoil and convinced him to lead the group. Maitland saw himself as a “doctor,” according to his heirs, able to quickly diagnose a problem and come up with a plan. “It was a natural evolution for him,” Jack says.

Vic later told the AP that upon joining, the association had “no money, no visibility and practically no members, but an awful lot of ambition to take care of the pre-59ers.’” He invested over $1 million of his own money into the organization, and turned his advertising company’s building in Fort Lauderdale into the NFL Alumni headquarters. “We help ballplayers in trouble, down on their luck,” he told the Miami Herald in 1977.

It worked. In 1987, he helped persuade NFL owners in 1987 to contractually agree to issue royalty payments to pre-’59ers who had put in at least five years of service. Maitland expanded the Alumni organization into 33 chapters (it now has over 40) and spearheaded its “Caring for Kids” charity program.

“He’s been instrumental in turning around the entire concept of the Alumni Association. He’s given it direction, purpose, goals,” former Dolphins defensive tackle Manny Fernandez told the Miami News in 1980. “The thing about it is, he has no personal goals. He does it because he believes in us as a group. He believes in our potential.”

The family has kept personal letters from various figures praising the Alumni Association’s charity efforts, including from then-commissioner Pete Rozelle, Ronald Reagan and even higher powers. “Dear Mr. Maitland, His Holiness Pope John Paul II was very pleased to learn about the National Football Alumni and their outstanding efforts on behalf of young people in the United States,” Cardinal Agostino Casaroli, the pope’s secretary of state, wrote in 1986. “The Holy Father also wishes to acknowledge the charitable and educational efforts of the NFL Alumni.”

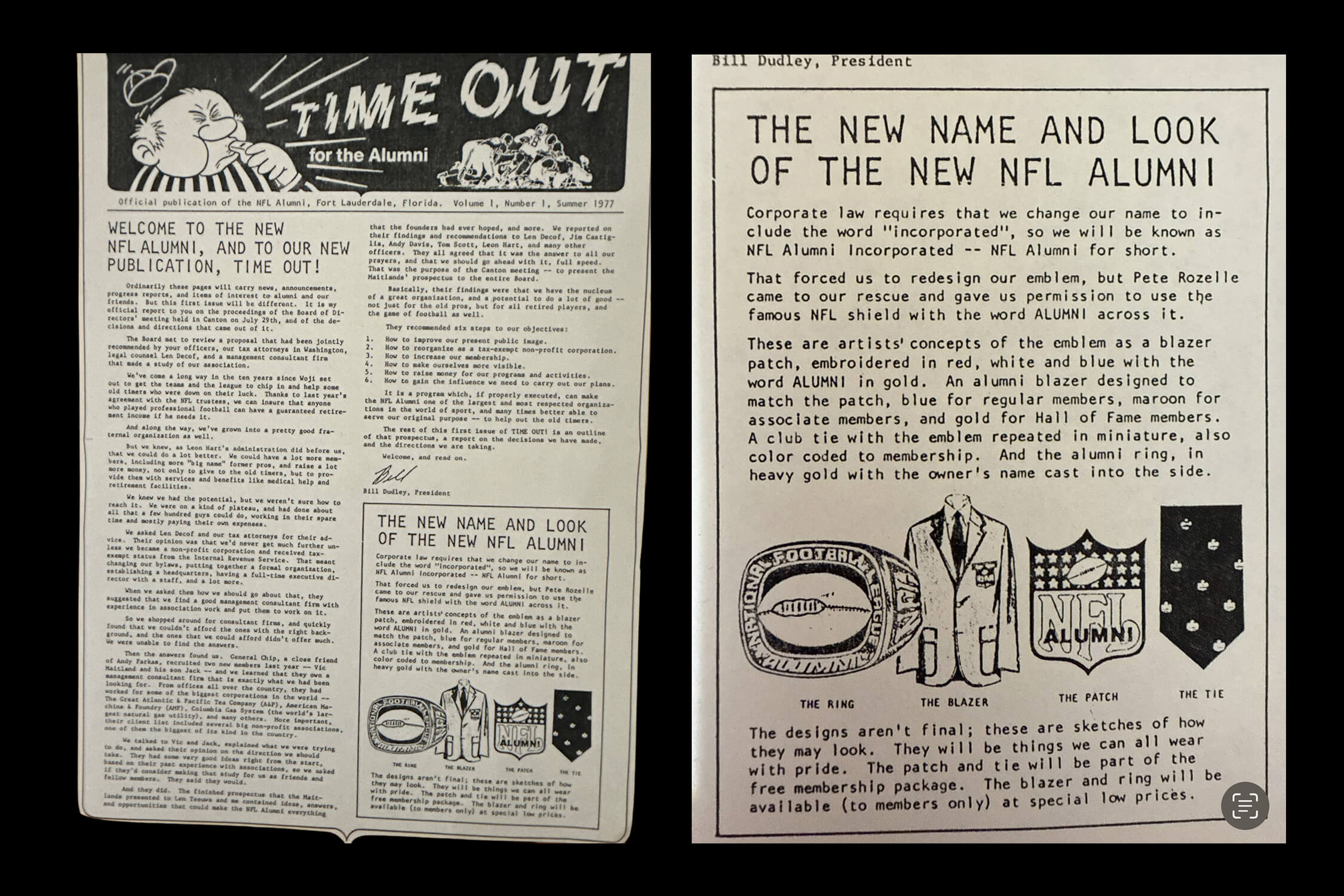

They’ve also kept documents about the Gold Jacket, such as the 1977 debut issue of the alumni association’s Time Out! Magazine, which included sketches of the original shield patch for the NFL alum logo and a prototype gold jacket. The family has a letter to Maitland from William J. Ray, then NFL Treasurer, dated April 4, 1979, giving Maitlaind “go-ahead on your new logo.”

The family reached out to leadership figures within the Pro Football Hall of Fame, NFL and Alumni Association as early as 2024, but came away with little to no acknowledgment. “It just fell on deaf ears,” Jack says. “Nobody would take our calls anymore.”

“It’s like leprosy,” Jim says. “We can’t touch that.”

But they knew where it might be coming from. Alumni Association senior vice president and chief operating officer Ken Coffey wrote Jamie an email in April 2025 that included a screenshot from a 1990 Washington Post article: “Jamie, I want to share with you the account below concerning your grandfather and why I believe that it is important for the NFPLA to be at arms length from him.”

The Post article described a civil suit filed against Maitlaind in Arizona on behalf of a local chapter claiming that money raised in Arizona was used to pay Maitland and his relatives “high salaries, expenses and leases on property Maitland rented to the organizations rather than being donated to the charities that contributors believed would benefit.”

“The civil consent judgement, approved by Judge Colin Campbell of Maricopa County Superior Court Friday, calls for the group to reduce payments to former chief executive Victor Maitland and to stay away from Maitland and his relatives,” the article read in part.

The Alumni Association was ordered to donate $75,000 to charity and Maitland to pay a $25,000 civil penalty, according to the Post, but there was no indictment issued. Still, Maitland’s reputation was tarnished. “The damage was done,” says Sandi Bishop, Vic’s other daughter.

Vic’s heirs claim that the civil suit could have been an attempt to curb his growing power and success — Maitland had been thinking about implementing even bolder ideas, such as creating a sort of alumni village for former players. But if that were the case, why would the Alumni Association issue the 2001 proclamation crediting Vic with the gold jacket and listing his other contributions, including the NFL Alumni Player of the Year Awards Dinner, which became the modern-day NFL Honors show held before every Super Bowl?

Instead, the proclamation said Maitland “was instrumental in transforming the National Football League Alumni, into a service organization that is nationally recognized and respected, has helped promote the rich heritage of professional football, that has assisted former players, particularly those in need, and, most importantly, that, for the past quarter of a century has made a positive difference in the lives of countless children and families nationwide.”

The Maitland family remembers how touched Vic was by the proclamation and the ceremony that followed, which was held in Orlando. “It was emotional,” says Jim, who was in attendance. “Dad was deeply touched. He stood up in front of a packed auditorium.”

Jim remembers talking about his father with Hall of Famers Lem Barney and Dick “Night Train” Lane that evening, but the ceremony wasn’t televised. Local papers apparently did not cover the event, either. “It never saw the light of day other than the inner working people of the NFL,” Jim says.

Maitland’s efforts to provide NFL alumni with an official uniform were outlined in an early issue of the association’s magazine. (Courtesy of the Maitland family)

Many of the people who might have further insight have died, including “Bullet” Bill Dudley, former president of the Alumni Association, who worked closely with Vic in the early days of the organization’s rise and died in 2010 at 88. In Dudley’s biography, written by his son-in-law Steve Stinson and published by Lyons Press in 2016, Stinson wrote that it was Dudley who came up with the idea of the gold jacket while watching the Masters Tournament on television.

“Bill had one of those ideas that really do seem like a lightbulb going off,” Stinson wrote. “What if the NFL Hall of Fame awarded a jacket to inductees and what if the NFLAA donated the jackets? He picked up the phone and got Vic Maitland. Maitland put together a proposal, went to Canton, and pitched it to the Hall of Fame board. … Maitland proceeded to have the jackets made.”

Stinson told The Athletic he believed his father-in-law’s account. “Other than his athletic skill, Bill Dudley was most widely known for his integrity and his humility. The man had a garage full of trophies, and that’s where he kept them — in his garage. That Bill could concoct an elaborate story and lie to me as we sat in his living room is simply unthinkable to me or to anyone who knew him and dealt with him. And, no, this wasn’t an old man recalling the past through a fog. Bill was still going to his office and working when he told me the story of the Gold Jacket. His memory was never dulled and he was never confused.”

Stinson also spoke with Maitlaind for the book. “(Vic) said, ‘I’m the one who thought that up.’ I think that’s a quote,” Stinson says. “I had to make a choice and I really didn’t know Vic, but I knew Bill, and I knew that Bill Dudley did not need a resume enhancement of any kind. … And so I simply went with that.”

Chusid, the Maitlands’ lawyer, said it was entirely possible that Maitland and Dudley discussed the topic, but, as Stinson wrote in the book, Maitland was the one who did something about it.

“Bill didn’t do anything affirmative to push the concept,” Chusid says. “That was clearly Vic.”

As the Maitlands await the legal process, they are looking forward to an exhibit at a local museum in Fort Lauderdale where Maitland will be honored. The exhibit will tentatively open in 2027, marking the 50-year anniversary of the establishment of the Alumni Association as a 501(c) (3) nonprofit organization.

The exhibit will highlight his entire life and legacy, including the gold jacket, according to Ellery Andrews, deputy director of HISTORY Fort Lauderdale. “We’re really honoring him in his life,” Andrews says.

Andrews isn’t shocked that something as iconic as the gold jacket could have its exact origins hidden for so many decades. “For us as historians and people who are in curation within the museum world, it’s actually not as surprising as you would think,” she says. “What people need to understand about generations above us is they often did not want recognition. For the older generations, it was the boots on the ground; we need to get this done because it is right, because it needs to be done and because there’s nobody else doing it, but that doesn’t mean they needed or necessarily wanted the recognition for doing it.

“It ends up falling to kids and grandchildren, and we see this all the time,” Andrews says. “We see this with the collections that get donated to us that are family collections.”

That’s something Jamie thinks about as she tries to share her grandfather’s story. She’s 39, having come of age in a world much different from her grandfather’s. In a sense, the public record is now being written on Tik Tok. On X. On Instagram. On YouTube. On websites. If history doesn’t exist there, she fears, younger generations may not look for it elsewhere.

She knows history isn’t static; it is constantly being unearthed, discovered. And it has to be shared. She feels an urgency to write down her family’s story before another February Hall of Fame enshrinement passes. Before it is too late.