This is the first of two articles on the relationship between water in Alberta and water in the Northwest Territories. This article focuses on water quantity – including how Alberta water usage impacts water levels in the NWT.

What happens to Alberta’s water can have a direct impact on NWT communities and ecosystems downstream. And there’s a lot going on with Alberta’s water right now.

That includes increasing water use by oil and agriculture industries, a proposed nuclear plant on Peace River, and upcoming changes to Alberta’s Water Act.

Here, we take a look at some of the biggest issues around the quantity of water in the NWT.

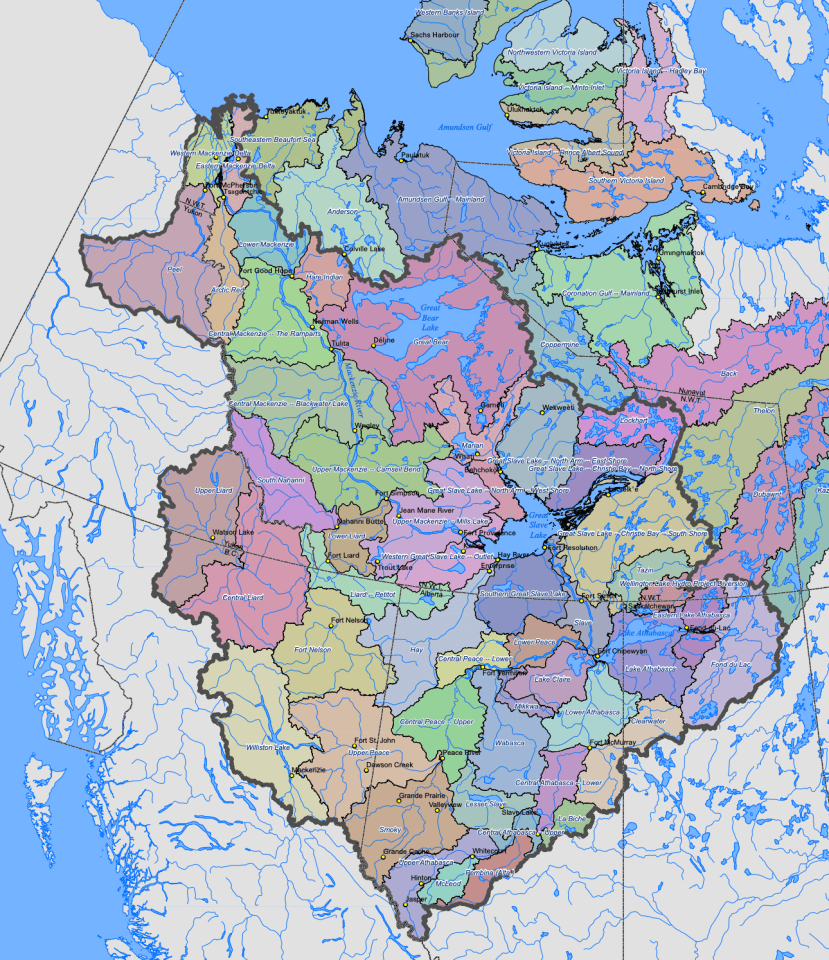

This federal map shows the watersheds of the NWT, with the Mackenzie River basin shown inside a large black outline. See the full-size map here. Water from much of Alberta, bottom centre, flows north into the NWT and ultimately out into the Arctic Ocean.

This federal map shows the watersheds of the NWT, with the Mackenzie River basin shown inside a large black outline. See the full-size map here. Water from much of Alberta, bottom centre, flows north into the NWT and ultimately out into the Arctic Ocean.

How are water levels now?

Water levels remain low across the territory as a result of the years-long drought that’s covered much of the NWT since 2022.

While there are a few exceptions within some smaller systems, overall recovery has been pretty minimal across the territory, says hydrologist Emma Gregory, who works at the NWT’s Department of Environment and Climate Change.

One bright spot is that there’s been pretty good early season accumulation in the Slave River Basin, which contributes about 80 percent of the water flowing into Great Slave Lake.

It could be an early indicator of maybe some recovery, Gregory said – but there’s still a lot of time until open water season. “We’ll have to keep monitoring to know the extent of recovery.”

Alberta has also been dealing with recurring and severe drought conditions – but the province’s water usage, particularly in the powerhouse agricultural region of southern Alberta, remains high.

Alberta’s water usage

In 2022, Canadian farmers used approximately 2.2 billion cubic metres of water to irrigate their crops. Of that, 1.6 billion cubic metres was used in Alberta.

Oil sands mining is also a significant water user.

According to the Alberta Energy Regulator, in 2024, nearly 1.2 billion cubic metres of water was used to produce almost 698 million barrels of oil from oil sands mining. Seventy-eight percent of that was recycled water – water a mine has already used, treated and then uses again – while 22 percent came from sources like the Athabasca River and groundwater.

However, Indigenous-led organization Keepers of the Water and others believe the real numbers are higher than those companies are reporting.

Independent consultant Ian Peace, who produced a 2019 thesis on oil sand tailings water in the Athabasca River, estimates the actual amount is 10-18 units of water to produce one unit of bitumen. “The low end, 10, represents what I think are best-case scenarios,” Peace said by email.

According to the Alberta Energy Regulator, water usage has increased steadily from 2013 to 2024, partly driven by new oil sands projects and expansions.

Companies are also using a higher proportion of water per barrel of oil – which would suggest they’re becoming less efficient with their water use.

Additionally, Alberta’s government has proposed a new pipeline to the northwest coast of British Columbia, recently declared a project of national interest by the federal government.

Jesse Cardinal, executive director of Keepers of the Water, says all of this is unsustainable.

“There’s billions of litres a year being extracted from the Athabasca River and the watersheds. The majority of it is not getting returned back into the water cycle,” she told Cabin Radio.

Pamela Narváez-Torres, a conservation specialist at the Alberta Wilderness Association, says the organization has a lot of concerns around water usage.

“Water is not doing great,” Narváez-Torres said. “We’ve seen some changes in water levels, and governments trying to compensate [and] balance the ecosystem with what industry needs, always giving more weight on that balance to industry.”

Oil sands companies Suncor, Imperial Oil and Canadian Natural Resources, all of whom operate oil sands mining operations in northern Alberta, were approached for this article. They did not respond to our request for comment on this issue, though Imperial Oil did respond on the topic of water quality, which we’ll examine in our next article.

Changes coming to Alberta’s Water Act

Bill 7: Water Amendment Act passed its third reading at the Legislative Assembly of Alberta on December 2. The bill can now come into force on proclamation; exactly when that happens is up to the government.

Most notably for the NWT, the bill makes it easier to carry out what Alberta calls “lower-risk” transfers of water between water basins. It also merges the Peace-Slave River basin and Athabasca River basin, turning the two ecologically distinct basins into one management entity.

Sandhill cranes on the Salt Plains in Wood Buffalo National Park in August 2021. The Athabasca River flows into the park. Sarah Pruys/Cabin Radio

Sandhill cranes on the Salt Plains in Wood Buffalo National Park in August 2021. The Athabasca River flows into the park. Sarah Pruys/Cabin Radio

The bill has received sharp criticism from environmental advocates and Indigenous communities.

In December, the Tallcree Tribal Government, Dene Tha’ First Nation and Sturgeon Lake Cree Nation announced a legal challenge against Bill 7, asserting that “the Province is using the Water Amendment Act to avoid its obligation to respect our treaty entitlement to safe and reliable water.”

Gerry Cheezie, a former Salt River First Nation chief presenting to the Dene National Assembly last week, said “merging river basins is ecologically reckless, scientifically unproven and a direct violation of treaty rights to safe and reliable water.”

“We really live in a petrol state where the Alberta government is fully accommodating the big-scale industries,” Cardinal said.

“Their solution is, ‘Well, the south is running out of water. We’ll just take water from the north.’ It’s really scary, because we’re already seeing the results of decades of mismanagement of water.”

What are NWT and Alberta governments doing?

In 2024, a report from Alberta’s auditor general found the province was failing to effectively manage its surface water.

Some of the key findings included, in the audit’s words, that Alberta’s Ministry of Environment and Protected Areas:

has no water conservation objectives in most basins;

does not know if existing water conservation objectives are working; and

lacks robust processes to monitor water pressures, assess risks, and decide when water conservation objectives are needed.

Meghan Beveridge, director of water monitoring and stewardship at the NWT’s Department of Environment and Climate Change, said the territorial government did have “some concerns” about the amendments to Alberta’s Water Act.

Those include concerns about whether increasing the amount of water use in Alberta would mean less water getting to the NWT, she said.

Beveridge said senior officials have had regular meetings with Alberta and communication has been good.

“We’ll be tracking the total amount of inter-basin transfers – if there are more applicants or transfers as a result of these changes, for example,” she said.

The NWT has also asked for Alberta to consider a cumulative cap on how much water could be used in inter-basin transfers. “We’ll continue to communicate with Alberta about concerns,” said Beveridge.

Alberta’s Ministry of Environment and Protected Areas did not respond to requests for comment.

Alberta has a new environment minister, Grant Hunter, who replaced Rebecca Schulz after she resigned on January 2. Hunter’s office also did not respond to requests for comment.

Suncor’s Fort Hills oil sands mine. Jason Woodhead/Flickr

Suncor’s Fort Hills oil sands mine. Jason Woodhead/Flickr

Cardinal said First Nations are being excluded from decisions and agreements about water governance.

“That needs to change,” she said. “It can’t just be the colonial Northwest Territories government speaking on behalf of all of the communities.”

In his presentation at the Dene National Assembly, Cheezie said pressure on the Peace-Slave watershed is accelerating a collective response from the Dene Nation and Treaty 8 Alberta, who expect to sign a memorandum of understanding on water this year to signal their unity, cooperation and shared resolve.

A water treaty is also being developed, Cheezie said, to bring together Indigenous governments across Canada to defend water under treaties 1 to 11. “Water does not recognize provincial boundaries,” he said. “Neither should our resistance.”

Dana Fergusson is the mayor of Fort Smith, a community just north of the NWT-Alberta border that sits on the Slave River. She worries that inter-basin water transfers might further deplete the river’s water levels.

“If you don’t have water, you don’t have a community,” Fergusson said.

“How can we give people drinking water if we don’t have access to be able to fill our reservoirs?”

Fergusson said the Thebacha Leadership Committee – herself, the chiefs of the Salt River First Nation and Smith’s Landing First Nation, the president of the Fort Smith Métis Council and the Thebacha MLA – are working to raise awareness of this at the territorial, provincial and federal levels.

“We’re worried,” she said.

“I just hope that our counterparts in the Alberta government and further up the chain in the federal office are hearing what we have to say, and really considering … the effects that it has outside of their borders.”

Nuclear project proposed

A company named Energy Alberta is in the early stages of developing a proposal for a nuclear power project on the Peace River.

A representative from the company said by email that the potential impact of the project on water flows will be evaluated over the next couple of years, through both the federal impact assessment process and a provincial water licence application.

The power station would use water from Peace River for cooling and other operations.

At full capacity, it would use “approximately 0.2 percent of the river’s medium annual flow to make up for water that evaporates as part of the power generation cooling system,” the company says.

Gregory, the NWT hydrologist, said the expected impact of a 0.2-percent draw on water levels would be “pretty minimal.”

What role does climate play?

Biology professor Roland Hall has studied the Peace-Athabasca freshwater delta for 25 years, looking at issues around water quantity, oil sands mining and climate change in collaboration with the Cold Regions Research Centre.

He points to a strong correspondence between drier or wetter episodes in the delta and global El Niño and La Niña variations.

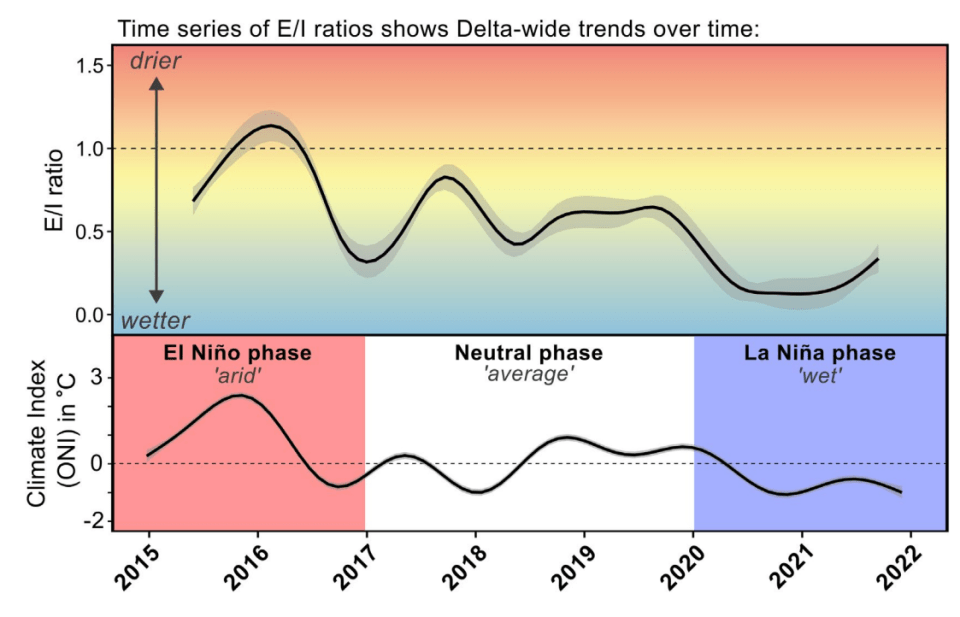

This graphic appears in a policy brief produced by Roland Hall and others this month. E/I ratio means evaporation-to-inflow. The authors argue this data shows the “strong influence of climate on freshwater availability” in the Peace-Athabasca Delta.

This graphic appears in a policy brief produced by Roland Hall and others this month. E/I ratio means evaporation-to-inflow. The authors argue this data shows the “strong influence of climate on freshwater availability” in the Peace-Athabasca Delta.

Typically, he said, withdrawals of water from industry form a very small proportion of the total flow.

“It’s only when the river naturally goes low that … the amount of water being taken up by the industry becomes a concern, in terms of having a big impact on water levels,” Hall said.

High-elevation snowpack and glacier runoff from the Rocky Mountains has also been reduced by climate change, he continued. That reduces the “alpine tap” that sends water into the Athabasca River and Peace River.

Meanwhile, water usage has been rising, and Hall said we’re reaching a critical point of concern around how much water we can use.

When will we hit that point? We may already be there, Hall said.

Recent years have seen ice roads disrupted in the winter and water levels too low for barges in the summer. Both can leave communities without essential supplies.

“Maybe that’s a sign that we’re already experiencing that crossroads,” said Hall.

“Maybe it’s going to just bring bigger and tougher challenges to deal with as we move forward.”

Related Articles