Russia is quietly testing a new plasma propulsion system that, if it performs as claimed, could dramatically change how long it takes to travel to Mars. Early results suggest a leap in speed and efficiency that has drawn attention precisely because it is not coming from NASA or private U.S. companies such as SpaceX.

The engine is being developed by the Troitsk Institute, part of Russia’s state nuclear corporation Rosatom. According to researchers involved in the program, the system could reduce interplanetary travel time from several months to roughly one to two months. Ground-based testing is currently underway, and the developers say the technology could be ready for space deployment by around 2030.

A Different Approach to Space Propulsion

Photo Courtesy: Autorepublika.

Unlike conventional chemical rockets, the new system relies on electromagnetic fields to accelerate charged hydrogen particles. This places it firmly in the category of electric or plasma propulsion, a field that has gained increasing global attention as space agencies look for more efficient ways to travel deeper into the solar system.

Chemical rockets deliver very high thrust for a short time, which is ideal for launching from Earth. However, they are inefficient for long-distance travel once a spacecraft is in orbit. Plasma engines, by contrast, generate much lower thrust but can operate continuously for long periods, gradually building up extremely high speeds while using far less propellant.

If the Russian system achieves its projected performance, it could have a major impact on how future missions to Mars and beyond are planned, both for scientific exploration and for potential military or logistical applications.

Testing Conditions and Early Performance Claims

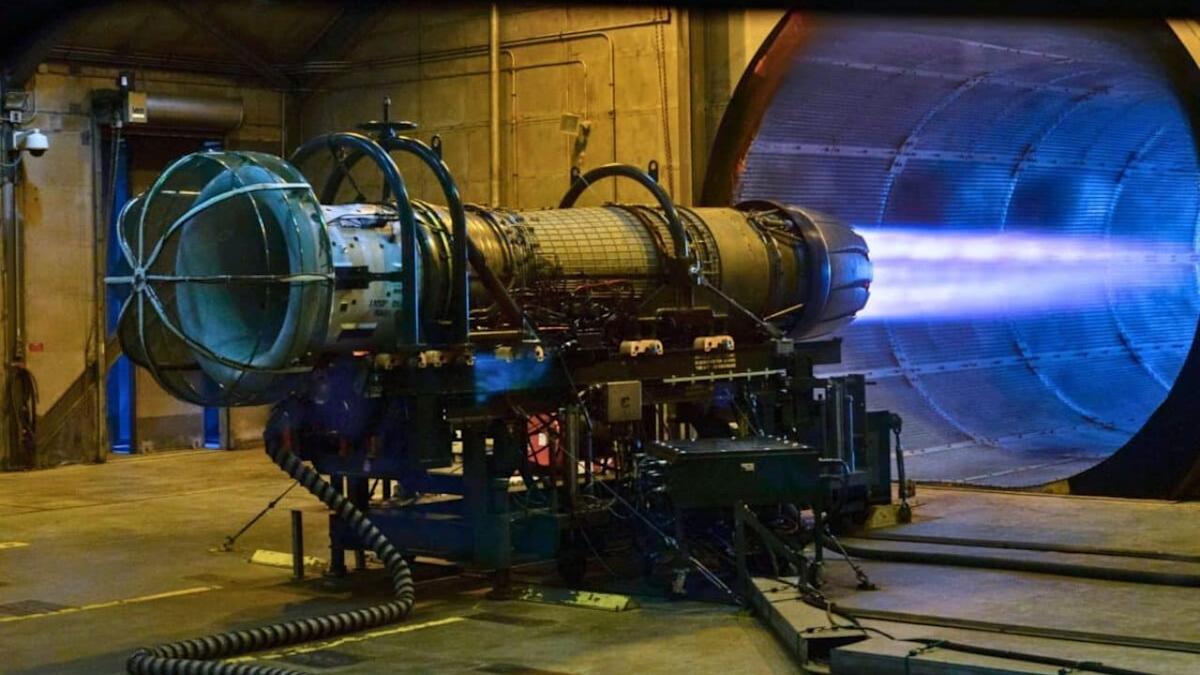

The prototype engine is currently being tested inside a 14-meter-long vacuum chamber designed to simulate space conditions. According to technical details reported by the Russian newspaper Izvestia, the engine operates at a power level of 300 kilowatts in a pulsed periodic mode and has already demonstrated a working lifespan of 2,400 hours. That duration would be sufficient for a full Mars mission, including acceleration and deceleration phases.

Researchers say the engine accelerates charged hydrogen particles, including protons and electrons, to speeds of up to 100 kilometers per second. By comparison, traditional chemical rockets typically achieve exhaust velocities of around 4.5 kilometers per second. This massive difference in exhaust velocity is the key to the engine’s potential efficiency and speed.

How the System Would Be Used in Space

The plasma engine is not intended to launch directly from Earth’s surface. A conventional chemical rocket would first carry the spacecraft into low Earth orbit. Once in space, the plasma engine would be activated to provide continuous thrust for the journey through deep space.

Officials involved in the project also note that the system could function as a space tug, moving cargo, modules, or satellites between different planetary orbits. This concept aligns with broader international interest in reusable orbital transport systems.

Nuclear Power and Engineering Challenges

Photo Courtesy: Autorepublika.

The engine uses hydrogen as propellant and relies on an onboard nuclear reactor to provide a constant energy supply. According to project researcher Yegor Biryulin, hydrogen’s low atomic mass allows for faster acceleration while reducing fuel consumption. Its abundance in space could eventually allow for in situ refueling, at least in theory.

The propulsion system uses two high-voltage electrodes to create directed plasma flow. Charged particles pass between them, forming a magnetic field that expels plasma and generates thrust. This design avoids the need to heat plasma to extreme temperatures, which reduces component wear and improves overall efficiency.

Rosatom documentation lists the projected thrust at 6 newtons, which is high for a plasma propulsion prototype. Even so, the thrust remains far lower than chemical rockets, meaning spacecraft would be designed for slow but continuous acceleration rather than short bursts of power.

Context and Open Questions

Plasma propulsion is already used in orbit on many satellites, including systems on OneWeb spacecraft and on NASA’s Psyche mission launched in 2023. Most existing plasma engines operate at exhaust velocities between 30 and 50 kilometers per second. The Russian claims of 100 kilometers per second would represent a significant step forward.

However, the technology remains unproven in space. Peer-reviewed scientific data have not yet been published, and the nuclear reactor design has not been disclosed. Nuclear-powered spacecraft raise complex safety, regulatory, and international approval issues, especially during launch.

While the concept is promising, the engine is still years away from practical use. Its projected readiness by 2030 will depend on continued testing, funding, and successful resolution of engineering and regulatory challenges.

This article originally appeared on Autorepublika.com and has been republished with permission by Guessing Headlights. AI-assisted translation was used, followed by human editing and review.