The Gates Foundation said Monday that it would commit $2.5 billion through 2030 to support dozens of different approaches for improving women’s health, from new medicines to prevent maternal mortality to vaccines to curb infections that disproportionately affect women.

The figure represents an increase of about a third in the foundation’s funding for women’s health and maternal health compared to the previous five years, and is a small illustration of the kinds of commitments that Bill Gates, the foundation’s chairman and founder, is making as he seeks to donate the vast majority of his $114 billion fortune before winding down the foundation over the next 20 years. It is the largest funding commitment the Gates Foundation has made in women’s health.

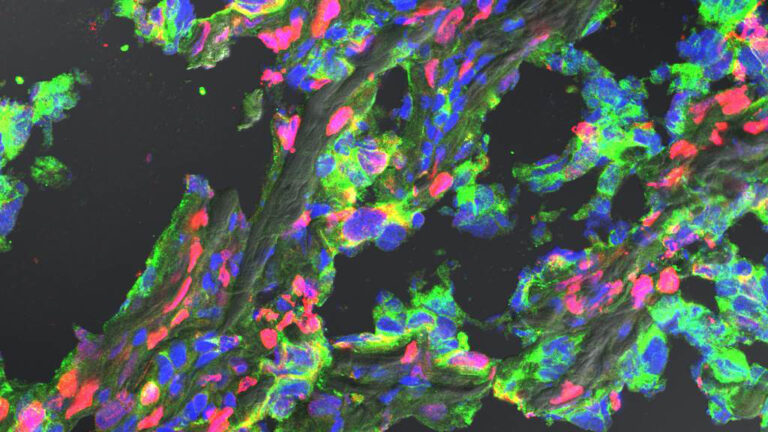

“Pregnancy is stunningly under-studied,” said Gates, who discussed the pledge during an event with STAT on Monday afternoon in Cambridge, Mass. He noted that The Gates Foundation is now the primary funder in research areas like the vaginal microbiome, which it believes could have importance both for pregnancy and the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases, and new non-hormonal contraceptives.

“Giving birth is still … very risky, particularly in low-income countries. Even conditions like preeclampsia and gestational diabetes aren’t as well understood for the rich world as they should be,” Gates told STAT.

Bill Gates discusses risks of pregnancy during an interview with STAT in Boston on Monday.

Alex Hogan/STAT

Experts in maternal and women’s health said the commitment represents a major new source of research funding at a time when the U.S. government is cutting both research related to women’s health and aid directed at maternal health; the field has been hit by reductions in grants from the National Institutes of Health, cuts to data monitoring efforts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the dissolution of the U.S. Agency for International Development.

The Gates Foundation said the goal of the new initiative is to address a long-running deficit in medicine that has disfavored women’s health — to the extent that the “typical” patient described to medical students has traditionally been male. In an article published in the BMJ last week, Ru Cheng, the foundation’s director of women’s health initiatives, said that only 1% of global research and development funding is allocated to women’s health issues outside of oncology, and that between 2013 and 2023, only 8.8% of NIH-funded research focused exclusively on women. While venture capital investment in women’s health grew by 300% between 2018 and 2023, it still accounts for just 2% of health care venture investments.

“For too long, women have suffered from health conditions that are misunderstood, misdiagnosed, or ignored,” said Anita Zaidi, president of the Gates Foundation’s Gender Equality Division, in a statement. “We want this investment to spark a new era of women-centered innovation — one where women’s lives, bodies, and voices are prioritized in health R&D.”

Although the Gates Foundation says that it aims to help women everywhere, most of its projects have a primary focus on health innovation in lower-income countries — although many of the same problems also afflict wealthy nations, and particularly the United States, which ranks 55th in the world in maternal mortality rates.

The vast majority of the funds — as much as 70% — will go to research and development. About a tenth will go to market introduction of new technologies or generating better data around them. Only about 4% will go to manufacturing, and 3% to advocacy.

The foundation provided a list of more than 40 existing projects it has funded that could fall under the commitment. They range from the very low-tech to the extremely high-tech. There is, for instance, a simple, low-cost plastic drape — think of a V-shaped plastic bag — that can be placed under a patient during childbirth to collect lost blood. Markings in the bags allow health care providers to rapidly identify when there is too much maternal blood loss.

There is also, though, funding for an upgraded type of ultrasound device that is both more compact than the one traditionally used during pregnancy and that uses artificial intelligence so the operator needs less expertise — potentially improving prenatal care in areas with fewer resources.

And the foundation is funding the most expensive type of project in health care — the creation of new medicines. For instance, funding will go to Comanche Biopharma, a Cambridge, Mass., biotechnology firm, that is developing a drug that targets a key protein involved in triggering preeclampsia, a condition that causes high blood pressure during pregnancy and results in the deaths of 45,000 mothers and the loss of half a million fetuses and infants annually, according the World Health Organization.

Comanche CEO Scott Johnson, who previously led the development of the blockbuster cholesterol drug Leqvio at The Medicines Company, said that the foundation’s impact goes beyond money.

“In fact, I would argue, although the money is incredibly important, the resources of the Gates Foundation are amazing,” Johnson said. “They have biostatisticians, they have drug modelers, they have lawyers who have looked at regulatory challenges in Third World countries and can help you figure out how you do a clinical trial in Ghana. They have enormous resources, and useful resources.”

New blood test could predict preeclampsia in the first trimester

In return for that support, Johnson said his company has agreed that if it does not develop its drug for low- and middle-income countries, the Gates Foundation will gain access to its intellectual property in ways that will allow it to make the product available. That, Johnson acknowledged, could make venture capitalists and large pharmaceutical companies that might partner with Comanche nervous.

However, Johnson said, in this case broad availability is a goal the company and the foundation share. “We’ve got to be able to find a way to deliver this drug in these countries or it’s not going to achieve its full value, and I mean its full societal value,” he said.

“It’s curious why some of these areas are so under-invested, because the rich world health burden on preeclampsia specifically is still, you know, very high,” Gates said.

Other high-tech approaches being funded by the Gates Foundation include self-injectable contraceptives, contraceptive patches, rapid diagnostics for sexually transmitted infections, and research to understand how the human microbiome affects maternal health and disease transmission. There is also a large slate of projects connected to ways in which the microbiome can affect women’s health generally, including during pregnancy.

Women’s health is an area that has been core to The Gates Foundation since its inception. In 1999, Gates and his wife at the time, Melinda French Gates, made a gift to Johns Hopkins University to start an institute of population and reproductive health; it is now named after Bill’s father, William Gates Sr., who died of Alzheimer’s.

From then on, issues related to women’s health and reproductive autonomy have remained central to the foundation’s mission, with French Gates often serving as a spokesperson on them, including in a 2012 TED Talk in which she argued that it was time “to put birth control back on the agenda.” That year the foundation co-hosted the London Summit on Family Planning.

Melinda and Bill Gates divorced in August 2021, and she chose to exit the Gates Foundation’s operations last May; her own charitable work is focused on women’s equality, including the type of political activism the Gates Foundation has avoided.

In 2022, a study backed by the Gates Foundation showed that one dose of the HPV vaccine might be as effective as two; that led the WHO to recommend one-dose schedules of the vaccine as well as two-dose ones.

The new efforts have the stamp of some of Bill Gates’ biggest successes in philanthropy. He has pushed efforts, like Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, that get relatively low-cost interventions like vaccines to children in countries that could previously not afford them. The Gates Foundation has even played a role in developing new vaccines, such as one for a type of meningitis, where there was not enough incentive for pharmaceutical companies to be interested.

An unusual FDA panel on antidepressant use during pregnancy elevated skeptics of the drugs

The foundation often notes that, since 2000, the number of children who die annually has decreased by half.

Some maternal health experts contacted by STAT praised the foundation’s R&D funding, but wondered if more could be achieved by focusing on existing solutions — particularly because funding by the U.S. government is already being cut.

“While I applaud this significant investment in research and development focused on women’s health and long-standing gender inequity, some of the most critical interventions that would save women’s lives aren’t innovative or high-tech,” said Bisola Ojikutu, Boston’s public health commissioner and an associate professor at Harvard Medical School. “For example, maternal mortality in low- and middle-income countries and among Black women in the U.S. is unacceptably high, and yet it is largely preventable.”

Addressing basic needs like access to health care, education, and nutrition security, she said, both during pregnancy and in the postpartum period, could be a first step. “I hope that this investment will include well-established strategies to address these basic needs, particularly as aid and federal funding are being cut,” she said.

Naima Joseph, an assistant professor of maternal health at Harvard Medical School, added: “I can’t say it’s not exciting but it also seems a little divorced from what on-the-ground people are facing given the federal funding cuts.”

The Gates Foundation, though, sees its role as paying for innovation that might not otherwise happen. It is one of the few organizations in recent decades, for instance, that has paid for the development of vaccines yet is not a pharmaceutical company.

“Innovation is our sweet spot at the Gates Foundation,” said Cheng, the foundation’s director of women’s health initiatives, in an interview with STAT. She recently joined the foundation after a career working at large pharmaceutical companies. “We do see the power of innovation to overcome limitations in health care.”

Gates himself is sharper, saying the foundation works about equally in funding health care delivery versus research and development.

“One thing we make very clear is we’re not able to replace what the U.S. government has canceled,” Gates said. “It’s just not our role to say, OK, the U.S. government wants to save money and so we’ll help them do that.”

In many areas, including malaria, tuberculosis, and non-hormonal contraception, Gates said the foundation is already the biggest spender globally. Also, for R&D, he noted, innovations the foundation funds will remain developed. But for health care delivery, the foundation’s support will eventually disappear. Sustainability requires that other sources of funding exists.

Even backed by his fortune, Gates said, there are limits to what the foundation can accomplish on its own. One of its goals, he and his associates say, is to get governments, pharmaceutical companies, and scientists to care about inequities in women’s health as well.

“We’d love to have other people work on this stuff,” Gates said. “It’s crazy that this stuff isn’t better funded. Drawing governments and other philanthropists in — we’ve had some success at that, and I’m putting more time into talking with other philanthropists about how impactful this work is. So I think we’ll have a lot of additional partnerships, certainly at the end of the 20 years.”

“Then we’re gone and so other people will have to step up in these areas.”