The darkness was still there, along with the doubt and fear.

“I was a romantic at heart, you know,” Bruce says. “So a dark romantic, I guess.”

Eventually the labor on the “Born to Run” single came down to recording overdubs and the vocal. Ensconced in a recording studio in the wee hours, Appel and Bruce seemed to try every idea that occurred to them. A string section. An ascending guitar riff repeating through the verse. A chorus of women chiming in on the chorus. An even bigger chorus of women oooh-ing behind the third verse. They’d work out a part, hire whatever musicians or singers were needed to get it on tape, then mix it all together to see what they had. Sometimes it would stick, sometimes they’d just laugh, shake their heads, and slice it out.

Bruce knew exactly what he wanted for the saxophone break. Then he spent ages working on it with Clarence Clemons, eight, ten, maybe twelve hours, playing the same notes over and over again, Bruce looking for a slightly different feel, a slightly different tone, a tiny adjustment to the rhythm of this passage, this pair of notes, this portion of that note.

While work on the instrumental track went on for weeks, it still didn’t rival Bruce’s laboring over the lyrics. He had always put energy into his narratives, but the pressure he felt to get “Born to Run” exactly right pushed him to a whole other level of perfectionism, determined to get every word, every nuance, every syllable flawless. Sometimes he’d be in the midst of a take, sing a few lines of a verse, shake it off, then take his notebook to a folding chair. He’d find a pen, open the book, look at the page, and just … think. He’d be there for a while. An hour, two hours, maybe more. Meanwhile, in the control room, Appel would be at his place at the board, recording engineer Louis Lahav in his. Impatience was not an option.

“There was a certain amount of self-punishment and self-thrashing for no good reason except for that was the only way I knew how to do it,” Bruce explains now. “I didn’t know how to do it some other way, so everybody got stuck with it.”

Still, for all that pressure to create, Bruce says he knew he was realizing the life he’d set out to have since he was 14 years old. “All I know is, hey, I’m on the road, I got a great band. We’re having the time of our lives. I’m not working 9 to 5, and I’m traveling around, staying in places that are nicer than my apartment. We’re meeting girls. You know, I felt like I was as good as anybody out there … but I was just taking it a day at a time.”

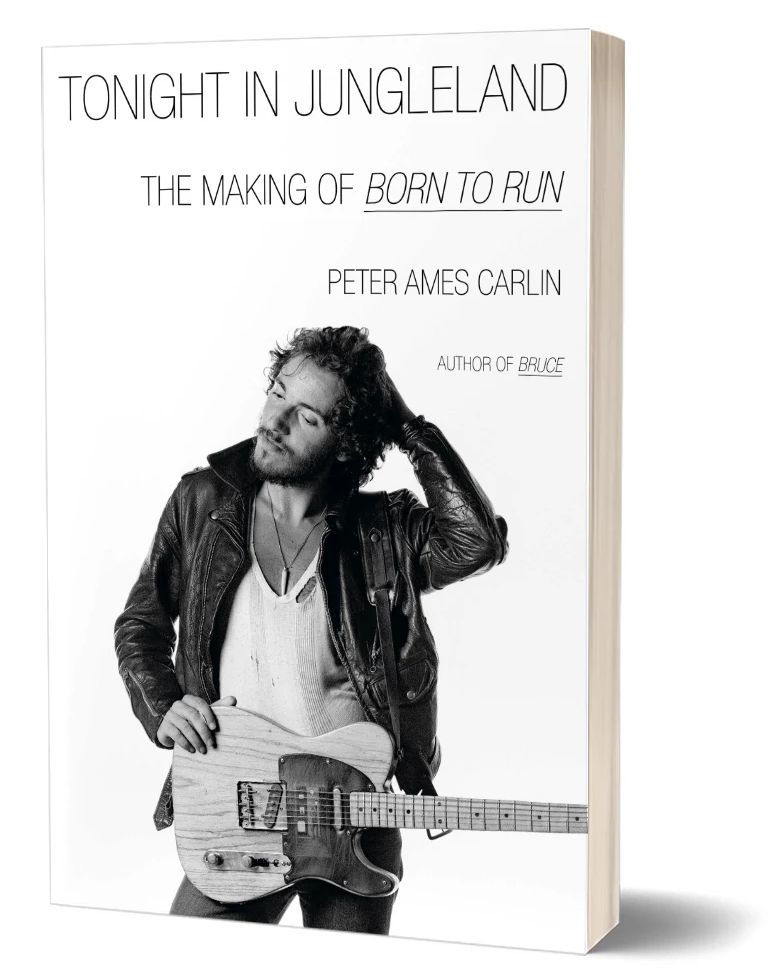

Carlin’s new book describes how the iconic album’s title track was shaped. Billboard would later call “Born to Run” “simply one of the best rock anthems to individual freedom ever created.”

Penguin Random House

Meanwhile, the nation in 1974 spun crazily toward some kind of doom. We’ve gotta get out while we’re young, Bruce sang, and the urgency in his voice was echoed by every note and drum stroke, the hard edge in the guitar, the cry of the organ, the growl and wail of the saxophone.

Finally the song felt finished.

Now it was August, right around the time of President Nixon’s resignation. The denouement of the Watergate scandal — what the freshly anointed President Gerald Ford called our long national nightmare — lifted at least a part of the nation’s psychic burden. Suddenly, the breeze carried a sense of new beginnings. A propitious time to move forward. They made a final mix of “Born to Run” and dubbed it onto a cassette.

Appel and Bruce walked from the manager’s midtown office up to the CBS building to play it for a record executive with their label. Bruce decided to wait in the lobby downstairs while Appel carried the tape up to the executive floor. When Appel returned to the lobby, he gave it to him straight: The music exec had only sort of listened as he took multiple phone calls, then said he hadn’t been able to absorb it.

Fifty years later, Bruce says, of the executive’s response, “I guess it wasn’t an easy song to absorb when you first heard it. Now people have heard it a thousand times, so it all sounds perfectly natural, right? But at first people said it sounded noisy.”

Still, as far as Appel was concerned, Bruce Springsteen shouldn’t have to take no from anybody. A new plan of attack revealed itself. It would require them to take a leap, and to risk aggravating the very executives who could help, or hinder, them. A career-sized risk, in other words. With Bruce’s record contract already in jeopardy, news of an unauthorized leak from a nonexistent future album might well have spurred the company to cut the rocker loose. But that possibility didn’t trouble Appel. The only question in his mind was how quickly he could get it done.

The manager made a list of all the radio DJs who’d played Bruce’s records, who’d had him on the air and/or attended his shows and/or professed their adoration for him. He arranged to make several dozen duplicates of the “Born to Run” master tape and wrote a cover letter for radio programmers and disc jockeys so they knew exactly what it was and why they had been chosen to play the song on their air.

Word of the new song sifted across town and then to Bruce-friendly stations in dozens of other cities. “We had stations all over the country,” says Appel. “Primary, secondary, tertiary markets, it didn’t matter; we had the nation covered.”

The plan worked. He quickly began to hear from the Columbia executive floor, whose occupants wanted to know what the hell Appel thought he was doing. But he was happy to weather the abuse. Now, at last, they were ready to listen.

Editor’s note: Partly as a result of Appel’s audacious marketing effort, Springsteen and his band finally received financial backing from their label to record the Born to Run album. After a year of intense studio work, the album was released in August 1975 to massive acclaim, with Billboard declaring the “Born to Run” track a “monster song with a piledriver arrangement … simply one of the best rock anthems to individual freedom ever created.”