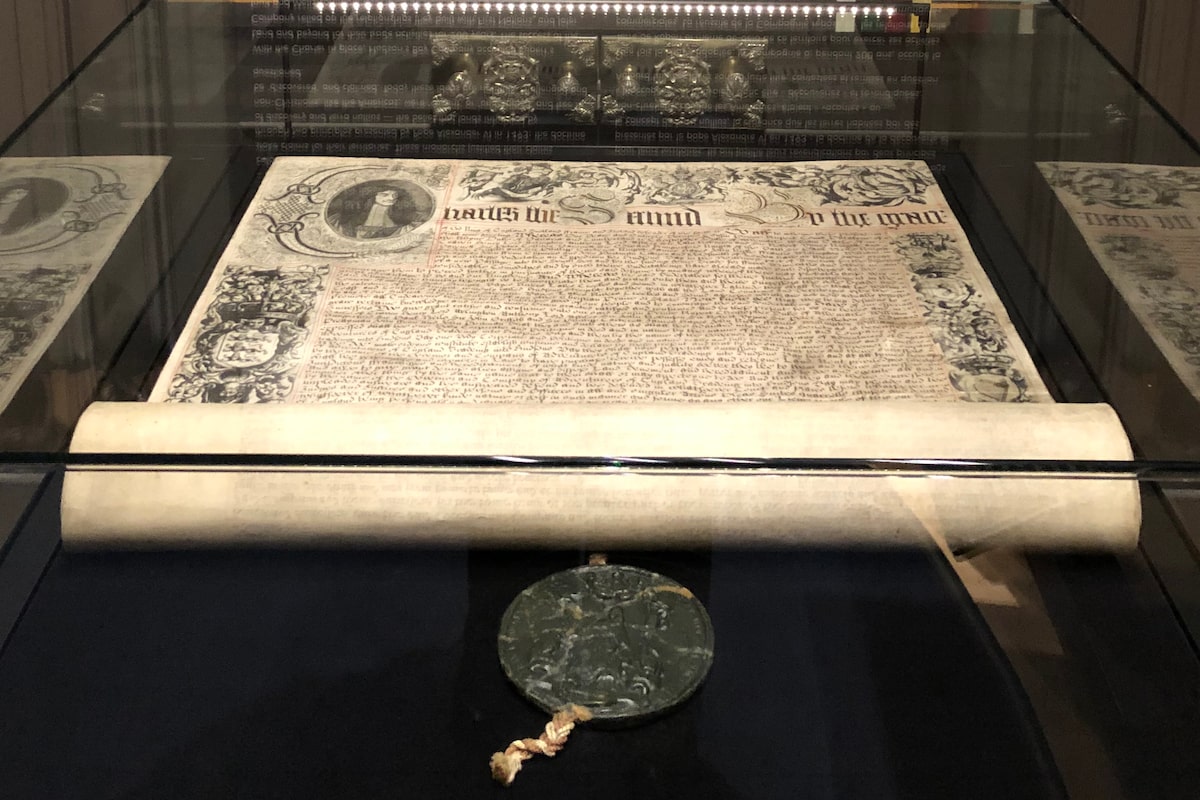

The 1670 royal charter signed by King Charles II establishing Hudson’s Bay on display at the Manitoba Museum, alongside other Hudson’s Bay artifacts.HO/The Canadian Press

When Kyra Wilson, Grand Chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, heard about the billionaire Weston family’s plan to buy the 1670 charter of the Hudson’s Bay Company and donate it to the Canadian Museum of History, she had two reactions.

While she feels that the $12.5-million bid is “such a beautiful gesture for the country,” she also had a question.

“When I think about this process with the charter, where is the respect to the First Nations that have been so negatively and deeply impacted by that charter?” Ms. Wilson said in an interview. “Why have we not been consulted on what happens with that?”

She is not the only one raising concerns about the transparency of the process to decide on the fate of a document that played a foundational role in Canada’s history. The charter, which carries the seal of King Charles II, bequeathed to the Hudson’s Bay a trading monopoly over roughly a third of what is now Canada – without the involvement or consent of Indigenous people who already lived there.

Opinion: Reconciliation is not a return to the past – it’s creating something new together

Cultural groups in the archival and museum sectors are now questioning why there was no consultation – before a deal was made in a surprise sale ahead of a planned auction – on how the charter should be handled.

“So much of this process has not unfolded in an open and transparent way,” said Rebecca MacKenzie, director of communications for the Canadian Museums Association. “It hasn’t really left space for a collective decision, which is of course what we would hope for.”

The Globe and Mail first revealed in April that the charter was included in a confidential memo distributed to potential bidders for the assets of Hudson’s Bay. Facing a financial crisis, Canada’s oldest retailer filed for court protection from its creditors in March and has since been forced to close all of its stores across the country. It is now in the process of winding up the business.

On the day the Globe article was published, reporting that the charter would be up for sale, the federal Department of Canadian Heritage wrote to Hudson’s Bay governor and executive chairman Richard Baker, saying the government had “been made aware through media reports that historical artifacts from the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) may be considered assets as part of the HBC’s liquidation process.” The letter went on to note that the charter would fall under the regulations on the Canadian Cultural Property Export Control List.

At the same time, other cultural organizations began scrambling for information on how the sale would proceed, and what measures would be put in place to ensure it remained in Canada.

Hudson’s Bay receives court approval to sell off six store leases for more than $5-million

“That was our first indication that something was happening,” said Anna Gibson Hollow, president of the Association of Canadian Archivists, which sent a letter in May to Mr. Baker and the court monitor overseeing the process, expressing concerns about the auctioning of artifacts including the charter. “We heard nothing back.”

That was, not until the news last week about the offer from the Westons’ holding company, Wittington Investments Ltd., to buy the charter “for immediate and permanent donation” to the Canadian Museum of History, pending court approval.

People who spoke to The Globe for this story all said that they were relieved to see the Westons’ offer would not just keep the charter in Canada, but ensure it is publicly accessible in a museum with the expertise to care for it.

“I certainly don’t question their ability to preserve and provide access to the charter. They will do a spectacular job,” Ms. Gibson Hollow said of the museum. “My concern is, why was there no consultation?”

The Wittington offer was unsolicited, according to court documents, and made directly to Reflect Advisors LLC, the advisory firm overseeing the Hudson’s Bay sale process. Wittington urged the firm not to allow the charter to be sold at auction. Instead, Hudson’s Bay brought the offer before the court for approval.

A hearing is set for Sept. 9, and the judge in the case has set a deadline of Aug. 21 for responding materials to be filed with the court, including from any parties opposing the deal.

News of the deal took a number of parties by surprise, because Reflect had informed other potential bidders that offers in advance of the auction would not be accepted, according to three sources with knowledge of the process. The Globe is not naming those sources because they were not authorized to speak publicly on the matter.

Representatives for Reflect, the Canadian Museum of History and Wittington declined to comment for this story.

A syndicate of the Bay’s senior lenders, represented by investment firm ReStore Capital LLC, support the transaction, according to court documents. Another senior creditor, Pathlight Capital LP, “does not oppose” the deal.

Inside the final days of Hudson’s Bay

Some experts raised concerns that under this plan, the charter would not be stewarded by Hudson’s Bay Company Archives at the Archives of Manitoba. After a 1994 donation of the Bay’s historical objects and records to the province of Manitoba and the Manitoba Museum, the archives already hold the majority of the company’s historical documents – including eight other versions of the charter, reflecting amendments made to it in later years.

“If one private organization has been given the opportunity to precede the bidding process, there should be equal opportunity to other private organizations to keep it in Canada – and making sure you’re talking to the stewards of the current collection,” said Heather Bidzinski, chair of the Association for Manitoba Archives.

In addition to the court process, the Wittington deal requires the Canadian Museum of History to hold consultations with Indigenous groups on how the charter should be shared with other institutions and presented.

“I think that’s a very important aspect,” said Leslie Weir, the Librarian and Archivist of Canada, noting that a number of cultural organizations and Indigenous groups will want to provide input.

“I think if you get the right outcome, where the charter is in a public institution, and it will be accessible to peoples across Canada – taking into account how the First Nations and Inuit and Métis, what their position is – it’s certainly better than an auction.”

Ms. Wilson, the Grand Chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, said that she does not necessarily oppose Wittington’s plan for the donation.

“But we always need to be included in these conversations as First Nations,” she said. “Anything that has to do with the history of our people, our ancestors, we need to be a part of that. And unfortunately, a lot of the times we’re not. And we’re only shared information after the fact.”