Some 6.7 million Australians work from home, but the practice is heavily skewed towards higher income earners, a new analysis has confirmed as surging underemployment figures suggest a growing number of Australians simply aren’t working enough for work from home (WFH) to be viable for them.

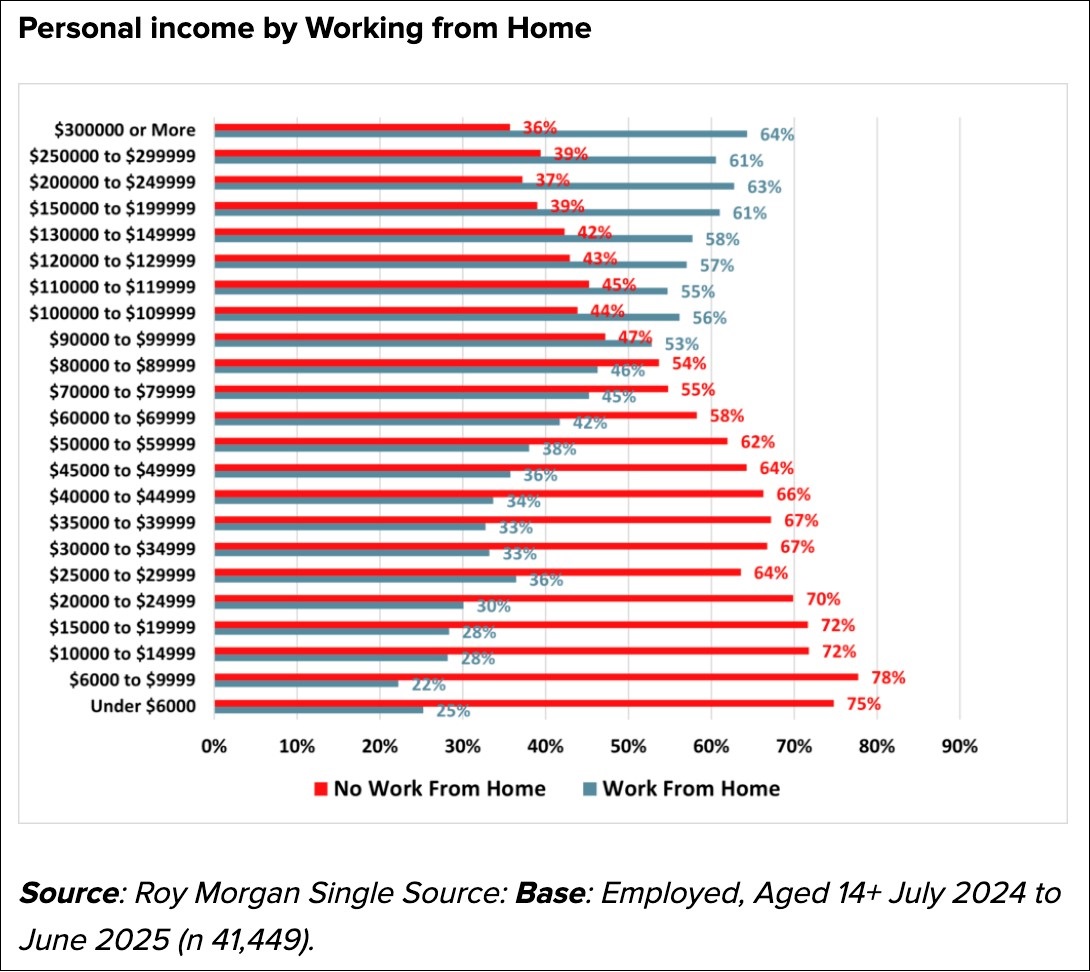

While 51 per cent of all full-time employees work from home at least some of the time, just a third of those earning $30,000 to $49,999 do so, research firm Roy Morgan found after interviewing 41,449 employed Australians from July 2024 to June 2025.

Higher-paid workers work from home more often, with “a notable shift” as salaries pass $90,000 and 61 per cent of those making $150,000 to $199,999 – a common salary for high-range developers, software engineers, process managers and other ICT roles – regularly working from home.

The results “highlight income as a strong driver of flexible work access,” the research firm noted, “with remote work heavily concentrated in higher salary brackets…. higher income positions are more likely to involve desk-based or technology-enabled work that can be performed remotely.”

Over half of Sydney, Melbourne, and Canberra workers reported working from home but rates were lower in Hobart (45 per cent), Adelaide (44 per cent), Brisbane (43 per cent), Perth (40 per cent), and the NT (34 per cent) – suggesting WFH is driven by local factors and employment mix.

Two thirds of finance and insurance industry workers work from home, with communication, property and business services, and public administration and defence doing so over half the time – yet as few as 31 per cent of retail, recreation and personal services, and transport and storage workers do so.

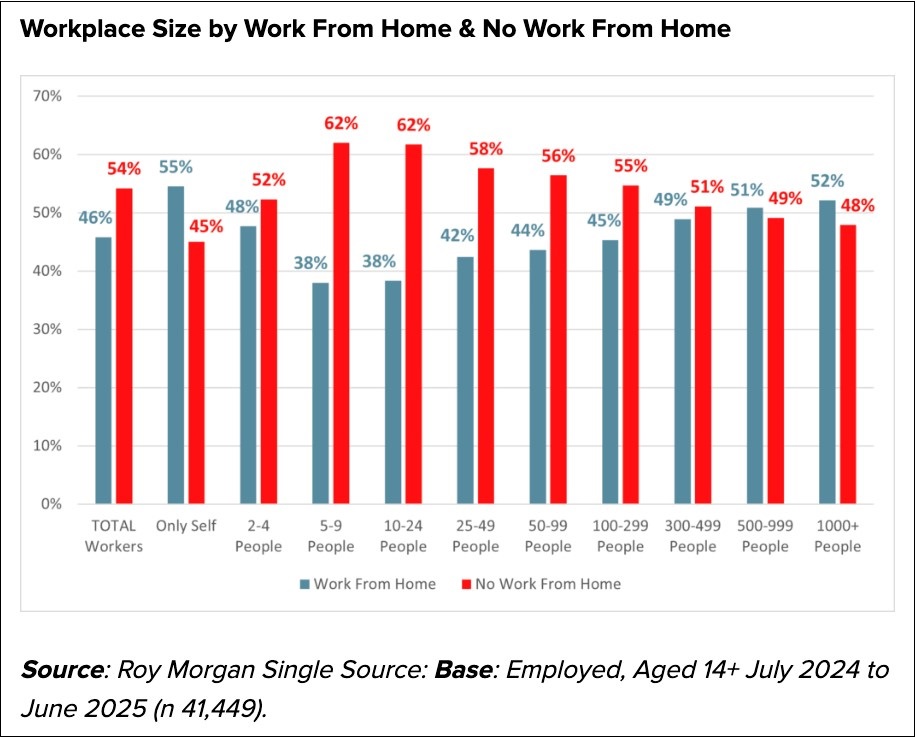

And while working from home is popular with self-employed and solo practitioners, just 38 per cent of those in small businesses from 5 to 24 employees saying they work from home.

The smaller the company you work for, the less likely you’ll be able to work from home. Source: Roy Morgan

WFH adoption increases with company size, with 52 per cent of employees in workplaces with over 1,000 employees doing so – a factor that Roy Morgan attributes to “a tipping point where larger organisations possess the resources and culture necessary to support WFH on a broader scale.”

WFH has already been normalised

The findings show that WFH arrangements “have become a permanent and distinct feature of Australia’s employment sector,” Roy Morgan CEO Michele Levine said, flagging the data’s confirmation of “significant variation by workplace size, sector, and income level.”

Clarity around the real-world adoption of WFH arrangements counters the mixed messages sent to Australian workers in recent years – with NSW last year forcing public servants back to the office amidst a WFH backlash that saw workaholic Tesla CEO Elon Musk describe working from home as “immoral”.

The likes of NAB and Dell have ordered workers back to the office, but Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg confirmed in January that “the [hybrid work] status quo is fine” – even as Prime Minister Anthony Albanese backed WFH and Victoria Premier Jacinta Allan promised to enshrine it in legislation.

At the time, Victorian Minister for Industrial Relations Jaclyn Symes said “more than a third of Australians are working from home regularly” – a more conservative estimation than Roy Morgan’s 46 per cent of all working Australians – and flagged hybrid work’s benefits for work/life balance.

As workers endure a surge in “focus-sapping” meetings, recent research has found that hybrid workers take fewer sick days than those who are forced to work from the office, spend less on commuting, and can only handle spending two days in the office before productivity flags.

Yet access to WFH remains uneven

Revelations of inequal WFH access highlight the challenges faced by workers in smaller companies and those in lower-paying jobs – many of whom are working less than they’d like to, with separate Roy Morgan figures warning of a festering underemployment plague.

Higher-paying jobs tend to be more conducive to working from home – but low rates among low-paid workers obscure a growing underemployment crisis. Source: Roy Morgan

The number of Australians who want to work more hours, but can’t, surged by 158,000 people to 1.74 million in July alone, the firm found, with 21.2 per cent of workers – over 1 in 5, equal to 3.38 million Australians – now considered to be underemployed.

Those figures mean more people are now underemployed than unemployed, suggesting that many employers are cutting back hours; workers are taking any work hours they can get because they cannot find full-time employment; or workers are reducing hours because they can’t work from home as much as their life and responsibilities require.

Extending WFH arrangements to all workers regardless of salary seems to be part of Allan’s motivation, with the state’s leader telling Labor Party colleagues that she will fight “bosses who cling to outdated ways of working because they don’t want to give up control.”

“Workers are simply asking to keep what they’ve already proven works for them, their families, and even their employers,” she said, arguing that “flexibility doesn’t weaken a workplace – it strengthens it.”

Ideas to improve working conditions will be flying thick and fast at Treasury’s upcoming Economic Reform Roundtable, where debates about WFH rights will dovetail with the ACTU’s call for a legislated four-day work week as leaders mull ways to boost productivity.

AI Group CEO Innes Willox, for one, has flagged the “urgent need for productivity uplifts to ensure real wages growth remains sustainable” – yet Roy Morgan’s Levine argues that “tackling Australia’s continuing high level of labour under-utilisation… must be front and centre at the roundtable.”