Anna Binta Diallo stands with her 2025 artwork, Sun Waves. The piece is appearing in Heliophile, an exhibition at Galerie Buhler Gallery in Winnipeg. (Karen Asher)

Anna Binta Diallo stands with her 2025 artwork, Sun Waves. The piece is appearing in Heliophile, an exhibition at Galerie Buhler Gallery in Winnipeg. (Karen Asher)

When Anna Binta Diallo would visit her grandfather in hospital, the artist would often find herself at Galerie Buhler Gallery, the contemporary art centre at St. Boniface Hospital in Winnipeg.

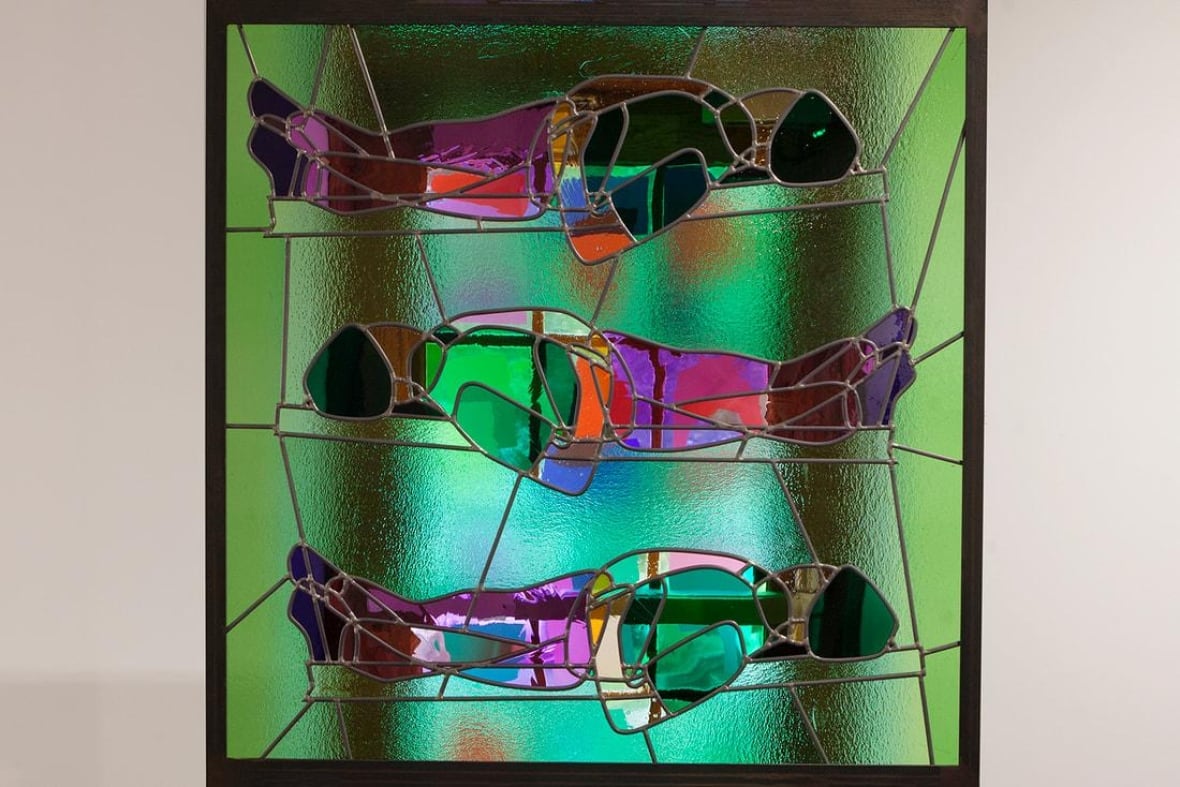

Near the gallery’s entrance, there’s a circular artwork made of colourful glass. It’s like a modern take on a gothic church window — a prairie tableau on a backdrop of emerald green.

A row of Winnipeg buildings appears in the middle of the piece, and right at its centre is a familiar landmark: the towering façade of the St. Boniface Cathedral. In 1968, a fire devastated the great stone edifice, but a local architect famously led the reconstruction efforts: Étienne Gaboury.

The glass artwork at GBG is also a Gaboury creation. He was both an architect and an artist. And he’s also Diallo’s granddad.

Architect and his artist granddaughter compete for book award in 2006

Artist Anna Binta Diallo talks about competing with her grandfather Étienne Gaboury for a book award. Aired May 6, 2006 on The Scene with Jelena Adzic.

Gaboury died in October of 2022. “Even though he’s gone, I connect to him through seeing what he’s done,” says Diallo. When she visits GBG, she marvels at her grandfather’s artwork. Sometimes, memories flood her mind. She might flash back to being a little kid, sitting at the table with her grandpa, the two of them drawing side by side. But wherever her thoughts may wander, the piece simply leaves her in awe.

“How on earth did he do this kind of stuff?” she says. “It’s complicated to work with glass.”

Diallo would know. Earlier this summer, the artist returned to GBG to open an exhibition of her own. It’s called Heliophile, and it features seven original works including four stand-alone sculptures made of fused and stained glass.

Anna Binta Diallo. Awakenings (First Light), 2025. (Karen Asher)

Anna Binta Diallo. Awakenings (First Light), 2025. (Karen Asher)

The artist has had a uniquely prolific year. In July alone, her work was appearing in six exhibitions across the country, including the Polygon Gallery in Vancouver and the Harbourfront Centre in Toronto (both shows are still on view). But in Heliophile, Diallo is unveiling an all new body of work which features a medium she’s never tried before.

Nominated for the Sobey Art Award in 2022, Diallo is best known for her work in collage. Her projects are often site specific and large in scale, and they explore themes of nostalgia, memory, and family heritage. The same subjects are mined in Heliophile too — with a special focus on her relationship with her grandfather.

The idea emerged through conversations with the gallery’s curator, hannah_g. As early as the spring of 2022, they’d discussed Diallo creating something for the space, and after Gaboury’s passing, they reconnected.

Anna Binta Diallo. Transitions (Illumination) , 2025. (Karen Asher)

Anna Binta Diallo. Transitions (Illumination) , 2025. (Karen Asher)

“I reached out to send her my condolences,” hannah_g says. Then, a couple days later, she contacted Diallo again. The curator had a burning question: “I wondered if she would be interested in making an exhibition that in some way related to or referenced her relationship with her granddad.”

Diallo had never considered the idea before. The subject matter was relevant to her practice; she’d long been concerned with themes of family, identity and growing up on the prairies.

“But [the work] was never explicitly about him,” she says. “I said, you know, I’d like some time to think about it, because I’m not sure how I’m going to approach this.”

Anna Binta Diallo. Bright Echoes, 2025. (Karen Asher)

Anna Binta Diallo. Bright Echoes, 2025. (Karen Asher)

Born in Senegal, Diallo grew up in the Winnipeg neighbourhood of St. Boniface, the heart of Manitoba’s Francophone community. Even as a little kid, she was aware of the mark her grandfather had made on the city. His buildings were part of her everyday landscape.

Diallo now teaches at the University of Manitoba, and her homecoming is a relatively recent development. The artist previously lived in Montreal, where she was based for 15 years. “Moving back to Winnipeg, I’m reminded of how much his presence is all around me,” she says.

Gaboury has been described as the province’s greatest architect, and he was responsible for many of its enduring landmarks, says Anne Brazeau, a writer and researcher at the Winnipeg Architecture Foundation. (The organization is developing an online exhibition about his life and work which is expected to launch in the fall.)

Moving back to Winnipeg, I’m reminded of how much his presence is all around me.- Anna Binta Diallo, artist

The Royal Canadian Mint is perhaps his “most impressive federal commission,” she says; the St. Boniface Cathedral reconstruction “launched his reputation as a major architect, especially of religious buildings.”

But in Brazeau’s opinion, his most defining achievement is The Precious Blood Church. Constructed in 1969, the building is clad in cedar shingles and suggests the shape of a tipi — a nod to Gaboury’s Métis heritage, and the predominantly Métis congregation. Diallo passes it every morning while walking her kids to school.

L’Église de Précieux Sang, or Precious Blood Church, at 200 Kenny St. in Winnipeg is shown in an undated photo. (Winnipeg Architecture Foundation)

L’Église de Précieux Sang, or Precious Blood Church, at 200 Kenny St. in Winnipeg is shown in an undated photo. (Winnipeg Architecture Foundation)

According to Brazeau, Gaboury’s signature flourish was his mastery of light, and Precious Blood is a prime example. “He is creative with his window placement,” she explains, “small, precise, strategically placed windows that would track the sun and especially the low, Manitoba winter sun.”

Heliophile, the title of Diallo’s exhibition, means lover of light. It’s a nod to her grandfather’s guiding principles; “he was very interested in light as an architect,” says Diallo. It’s become an important aspect of her own work as well.

In her collage art, Diallo often creates cut-outs of human figures. These silhouettes are faceless yet somehow familiar, and she fills each outline with found imagery in a patchwork style. As the saying goes, they contain multitudes. The different textures and colours Diallo incorporates in each composition suggest layered narratives and identities.

Anna Binta Diallo. Awakenings (Memory Light), 2025. (Karen Asher)

Anna Binta Diallo. Awakenings (Memory Light), 2025. (Karen Asher)

In Heliophile, Diallo continues to play with silhouettes. Many of the figures are girls — daydreamers who seem to float on separate planes of space and time. When they overlap, their colours combine, casting a blended palette of colourful light onto the gallery floor.

In each piece, Diallo says she’s made “little winks” to her family lore — details like memories of summer days at the beach or her grandfather’s habit of collecting rooster knick knacks. She was reflecting on the concept of lineage while developing the body of work. “It’s a meditation on life, on the journey of life, the cycles of life and time and perhaps memories as well,” she says.

Installation view of Heliophile by Anna Binta Diallo at Galerie Buhler Gallery in Winnipeg. (Karen Asher)

Installation view of Heliophile by Anna Binta Diallo at Galerie Buhler Gallery in Winnipeg. (Karen Asher)

To fabricate the free-standing glass artworks which appear in Heliophile, Diallo collaborated with Prairie Studio Glass in Winnipeg. The exhibition also features a video projection and two installation works — vinyl cut-outs which Diallo has collaged on the gallery’s walls and windows. The artist says they serve as a bridge between her past works and the new pieces in glass.

Since opening in June, Heliophile has drawn a unique mix of patrons, as one might expect of a hospital venue. Its regular patrons include patients, hospital staff, caregivers.

“It’s definitely a unique space,” says Diallo. “From the get-go, it was something I was thinking about, like who would be coming, how would they interpret the work, or what state of mind would they be in if they came in to see the show.”

After all, she’d been in their shoes a short time ago. Says the artist: “I want them to feel a sort of calmness, but also a jolt of joy.”

Installation view of Heliophile. The exhibition is on at Galerie Buhler Gallery in Winnipeg to Aug. 22. (Karen Asher)

Installation view of Heliophile. The exhibition is on at Galerie Buhler Gallery in Winnipeg to Aug. 22. (Karen Asher)

Heliophile. Anna Binta Diallo. To Aug. 22. Galerie Buhler Gallery (409 Tache Ave.), Winnipeg. www.galeriebuhlergallery.ca